Humorist

A humorist (American and British English) or humourist (alternative British spelling) is an intellectual who uses humor in writing or public speaking, but is not an artist who seeks only to elicit laughs. Humorists are distinct from comedians, who are show business entertainers whose business is to make an audience laugh. It is possible to play both roles in the course of a career.

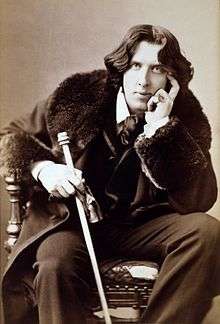

The iconic humorist

Mark Twain (pen name of Samuel Langhorn Clemens, 1835–1910) was widely considered the "greatest humorist" the U.S. ever produced, as noted in his New York Times obituary.[1] It's a distinction that garnered wide agreement, as William Faulkner called him "the father of American literature".[2]

The United States national cultural center, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, has chosen to award a Mark Twain Prize for American Humor annually since 1998 to individuals who have "had an impact on American society in ways similar to the distinguished 19th century novelist and essayist best known as Mark Twain".[3]

Distinction from a comedian

Humor is the quality which makes experiences provoke laughter or amusement, while comedy is a performing art. The nineteenth century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer lamented the misuse of humor (a German loanword from English) to mean any type of comedy. A humorist is adept at seeing the humor in a situation or aspect of life and relating it, usually through a story; the comedian generally concentrates on jokes designed to invoke instantaneous laughter. The humorist is primarily a writer of books, newspaper or magazine articles or columns, stage or screen plays, and may occasionally appear before an audience to deliver a lecture or read a piece of his or her work. The comedian always performs his or her work for an audience, either in live performance, audio recording, radio, television, or film.[4]

Phil Austin, of the comedy group the Firesign Theatre, expressed his thoughts about the difference in 1993 liner notes to the Fighting Clowns allbum:[5]

To me, there is a great difference between a humorist and a clown, and I had hoped that life for the Firesign Theatre would have led more toward the world of Mark Twain than the world of Beepo. The humorist is a happy soul; he comments from the sidelines of life, safe behind the keyboard or pen; not forced to mold his thinking to the direct response of an audience, he has indirection on his side. He has time to think. Beepo, on the other hand, takes his chances directly facing—or mooning—the audience; a buffoon, a patsy, a performer, he is out in the open and his audience, unlike a humorist's, becomes necessarily half-friend and half-enemy.

Mark Twain prize

Despite the name, conference of the Kennedy Center's Mark Twain Prize does not make the awardee a humorist. As of 2019, the center has chosen to confer the prize on twenty-one comedians[6] and one playwright;[3] only two recipients, the comedian Steve Martin and the playwright Neil Simon, are commonly recognized as humorists in the sense of Twain.

Notable humorists

American

- Renowned polymath Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), as a newspaper editor and printer, became one of America's first humorists, most famously for Poor Richard's Almanack published under the pen name "Richard Saunders".

- Ring Lardner (1885–1933) was a sports columnist and short story writer best known for his satirical writings about sports, marriage, and the theatre.

- Robert Benchley (1889–1945), best known for his work as a newspaper columnist and film actor, began writing humorously for The Harvard Lampoon while attending Harvard University, and for many years wrote essays and articles for Vanity Fair and The New Yorker.

- H. L. Menken (1880–1956) was a journalist, satirist, cultural critic and scholar of American English.[7] Known as the "Sage of Baltimore", he is regarded as one of the most influential American writers and prose stylists of the first half of the 20th century. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians and contemporary movements. He is known for dubbing the Scopes trial "the Monkey Trial".

- James Thurber (1894–1961) was a cartoonist, author, journalist, playwright, and celebrated wit, best known for his cartoons and short stories published mainly in The New Yorker.

- George S. Kaufmann (1889–1961) was a playwright, theatre director and producer, and drama critic. He wrote two Broadway musicals for the Marx Brothers: The Cocoanuts, and Animal Crackers.

- Bennett Cerf (1898–1971) was one of the founders of the publishing firm Random House, known for his own compilations of jokes and puns, for regular personal appearances lecturing across the United States, and for his television appearances on the panel game show What's My Line?[8]

- Jean Shepherd (1921-1999) was a radio and literature humorist best known for writing the book In God We Trust, All Others Pay Cash which was later adapted to the 1983 movie A Christmas Story.

- Art Buchwald (1925–2007) wrote a political satire op-ed column for The Washington Post, which was nationally syndicated in many newspapers.

- Garrison Keilor (born 1942) is an author, storyteller, voice actor, and radio personality, best known as the creator and host of the Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) show A Prairie Home Companion from 1974 to 2016. He created the fictional Minnesota town Lake Wobegon, the setting of many of his books. He created and voiced the hardboiled detective parody character Guy Noir on his radio show.

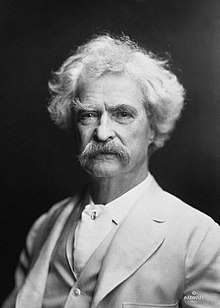

Britain and Ireland

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) was an Irish poet and playwright known for his biting wit.

- Jerome K. Jerome (1859–1927) was an English writer and humorist, best known for the comic travelogue Three Men in a Boat.

- P. G. Wodehouse (1881–1975) was one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century.[9]

- Alan Coren (1938–2007) could be considered the English equivalent of Bennett Cerf: a writer and satirist who was well known as a regular panelist on the BBC radio quiz The News Quiz and a team captain on BBC television's Call My Bluff. Coren was also a journalist, and for almost a decade was the editor of Punch magazine.

- Tom Sharpe (1928–2013) was a satirical novelist, best known for his Wilt series, as well as Porterhouse Blue and Blott on the Landscape.

- Terry Pratchett (1948–2015) was an author known for comic fantasy, most notably a series of 41 existentialist and political satire novels set in the Discworld universe. He was strongly influenced by Wodehouse, Sharpe, Jerome, Coren,[10] and Twain.[11]

Women

- Dorothy Parker (1893–1967), a writer for Vanity Fair, Vogue and other magazines, playwright, and a close friend of Benchley, was known for her biting, satirical wit.

- Erma Bombeck (1927–1996) was a newspaper columnist and writer of 15 books who specialized in humorously describing midwestern suburban home life.

- Fran Lebowitz (born 1950) writes sardonic social commentary from a New York City point of view.

Other countries

- Kajetan Abgarowicz (1856–1909) was an Armenian-Polish journalist, novelist and short story writer.

- Sholom Aleichem (1859–1916) was the pen name of the leading Yiddish author and playwright Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich, on whose stories the musical Fiddler on the Roof was based.

Comedians who become humorists

Sometimes a comedian will adopt a writing career and gain notability as a humorist. Some examples are:

Will Rogers (1879–1935) was a vaudeville comedian who started doing humorous political and social commentary, and became a famous newspaper columnist and radio personality during the Great Depression. He is an exception to the education rule, as he only completed a tenth grade education.[12]

Cal Stewart (1856–1919) was a vaudeville comedian who created the character Uncle Josh Weathersby and toured circuses and medicine shows. He befriended Twain and Rogers, and in 1898 became the first comedian to make sound recordings, on Edison Records.

Garry Moore (1915–1993), known as a television comedian who hosted several variety and game shows, after his 1977 retirement became a regular humor columnist for the newspaper The Island Packet of Northeast Harbor, Maine, with a column titled "Mumble, Mumble". He later released a book of his columns under the same name in the early 1980s.

Victor Borge (1909–2000) was a Danish-American comedian known for bringing humor to classical music. He wrote three books, My Favorite Intermissions[13] and My Favorite Comedies in Music[14] (both with Robert Sherman), and the autobiography Smilet er den korteste afstand ("The Smile is the Shortest Distance") with Niels-Jørgen Kaiser.[15]

Peter Ustinov (1921–2004) was an English comic actor who wrote several humorous plays and film scripts.

Woody Allen (born 1935), known as a comedian and filmmaker, early in his career worked as a staff writer for humorist Herb Shriner.[16] He also wrote short stories and cartoon captions for magazines such as The New Yorker.

Steve Martin (born 1945), comedian and actor, wrote Cruel Shoes, a book of humorous essays and short stories, in 1977 (published 1979). He wrote his first humorous play Picasso at the Lapin Agile in 1993, and wrote various pieces in The New Yorker magazine in the 1990s. He later wrote more humorous plays and two novellas.

Hugh Laurie (born 1959) is an English comic actor who worked for many years in partnership with Stephen Fry. He is a fan of the English humorist P. G. Wodehouse, and has written a Wodehouse-style novel.[17]

References

- "Obituary (New York Times)". Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- Jelliffe, Robert A. (1956). Faulkner at Nagano. Tokyo: Kenkyusha, Ltd.

- "The Kennedy Center Mark Twain Prize for Humor". Kennedy-center.org. 2017. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- Study.com. "Humorist vs Comedian: What is the Difference?". Study.com. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- Austin, Phil (1993). Fighting Clowns (liner notes). Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- The Kennedy Center revoked Bill Cosby's Mark Twain award in 2018.

- "Obituary", Variety, February 1, 1956

- Whitman, Alden (August 29, 1971). "Bennett Cerf Dies; Publisher, Writer; Bennett Cerf, Publisher and Writer, Is Dead at 73". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- Voorhees, Richard (1985). "P.G. Wodehouse". In Stayley, Thomas F. (ed.). Dictionary of Literary Biography: British Novelists, 1890–1929: Traditionalists. Detroit: Gale. pp. 341–342. ISBN 978-0-8103-1712-3.

[I]t is now abundantly clear that Wodehouse is one of the funniest and most productive men who ever wrote in English. He is far from being a mere jokesmith: he is an authentic craftsman, a wit and humorist of the first water, the inventor of a prose style which is a kind of comic poetry.

- "Terry Pratchett". Guardian Unlimited. September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- "Interview de Terry Pratchett (en Anglais) (Interview with Terry Pratchett (in English))". Nathalie Ruas, ActuSF. June 2002. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- "Adventure Marked Life of Humorist". The New York Times. August 17, 1935. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Borge, Victor; Sherman, Robert (August 1971). My favorite intermissions. Doubleday. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- Borge, Victor; Sherman, Robert (1980). Victor Borge's My favorite comedies in music. Dorset Press. ISBN 978-0-88029-807-0. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- Borge, Victor; Kaiser, Niels-Jørgen (2001). Smilet er den korteste afstand -: erindringer (in Danish). Gyldendal. ISBN 978-87-00-75182-8. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- "Woody Allen: Rabbit Running". Time. July 3, 1972. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- Host: James Lipton (31 July 2006). "Hugh Laurie". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 12. Episode 18. Bravo.

External links

- Henry, Patrick (April 15, 2013). "Don't Call Me a Comedian". Retrieved December 7, 2017.