Hukbalahap

The Hukbalahap (Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon; English: The Nation's Army Against the Japanese), or Hukbong Laban sa Hapon (Anti-Japanese Army), was a socialist/communist guerrilla movement formed by the farmers of Central Luzon. They are popularly known as the "Huks". They were originally formed to fight the Japanese, but extended their fight into a rebellion against the Philippine government, known as the Hukbalahap Rebellion, in 1946. It was put down through a series of reforms and military victories by the Philippines' Secretary of National Defense, and later President, Ramon Magsaysay.[2]

| Hukbalahap | |

|---|---|

| Participant in the Philippine resistance against Japan during the Second World War and the Hukbalahap Rebellion | |

Flag of the Hukbalahap (from 1950)[1] | |

| Active | 1942–1954 |

| Ideology | Marxism-Leninism Anti-Japanese imperialism (until 1945) Anti-Americanism (from 1946 until 1954) |

| Leaders | Luis Taruc Casto Alejandrino |

| Headquarters | Pampanga |

| Area of operations | Central Luzon |

| Allies | |

| Opponent(s) | |

A monument dedicated to the Huks in Cabiao, Nueva Ecija was constructed to honor their actions during the Second World War.[3]

Name

As originally constituted in March 1942, the Hukbalahap was to be part of a broad united front resistance to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.[4]:31 This original intent is reflected in its name: "Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon", which means "People's Army Against the Japanese."

By 1950, the Communist Party of the Philippines (PKP) had resolved to reconstitute the organization as the armed wing of a revolutionary party, prompting a change in the official name to Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan, [4]:44 (HMB) or "Peoples' Liberation Army," likely in emulation of the Chinese People's Liberation Army.

Notwithstanding this name change, the HMB continued to be popularly known as the Hukbalahap, and the English-speaking press continued to refer to it and its members, interchangeably, as "The Huks" during the whole period between 1945 and 1952.

Background

The Hukbalahap movement has deep roots in the Spanish encomienda, a system of grants to reward soldiers who had conquered New Spain, established in 1570. This developed into a system of exploitation. In the 19th century, Filipino landlordism, under the Spanish colonization, arose and, with it, further abuses.[5]:57 After the opening of ports in Manila, the Luzon economy was transformed to meet the demands for exports of rice, sugar, and tobacco. Landowners increased demands on farmers, who rented parcels of land. These demands included increased rents, demands for proceeds from the sale of crops, and predatory lending agreements to fund farm improvements.[6]:24, 26 Only after the coming of the Americans were reforms initiated to lessen tensions between tenants and landlords. The reforms, however, did not solve the problems and, with growing political consciousness produced by education, peasants began to unite under educated but poor leaders. The most potent of these organizations was the Hukbalahap, which began as a resistance organization against the Japanese but ended as an anti-government resistance movement.[7]

Inception during World War II

The idea of a guerrilla organization was conceived as early as October 1941, months before the Philippines' entry to World War II.[4]:30 As early as 1941, Juan Feleo, a well-known peasant leader and member of the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas, had begun to mobilize peasants in his home province of Nueva Ecija for the conflict. Pedro Abad Santos, founding member of the Socialist Party of the Philippines, had also ordered Luis Taruc to mobilize forces in Pampanga.[4]:31–32

At the outbreak of the Second World War in the Philippines and the capture of Manila, top-ranking leaders of the PKP were captured by the Japanese military. Crisanto Evangelista, its founder, was among those who were captured and was executed in 1942. Abad Santos was similarly captured, but was released in 1943.[6]:37 Dr. Vicente Lava took the reins of the PKP and tried to re-organize the party.

In February 1942 a "struggle conference" was held in Cabiao, Nueva Ecija to discuss organization, strategy, and tactics.[4]:31 Members of the PKP, the Popular Front Party, the League for the Defense of Democracy, KPMP, AMT, and KAP convened to create a structure for unified resistance against the Japanese.[6]:38

A united front tactic was agreed upon as a means of attracting the broadest sections of population, not necessarily communists. A three-front resistance was agreed upon: military, political, and economic. The military aim was to harass the Japanese continuously and keep it off-balance so as to prevent it from focusing on activities aimed at winning the goodwill of the people. The political aim was to discredit the Japanese-sponsored republic and build the concept of a functioning democracy as a grass roots level, while the economic objective was to prevent the enemy's looting.[4]:31 The result was the creation of the Central Luzon Bureau, an organization meant to lead resistance against the Japanese. Key positions were filled out as follows:[6]:38

| Department | Position | Name |

|---|---|---|

| General Secretary | Vicente Lava | |

| Organizational Department | Chairman | Mateo del Castillo |

| United Front Department | Chairman | Juan Feleo |

| Education Department | Chairman | Primitivo Arrogante |

| Finance Department | Chairman | Emeterio Timban |

| Military Department | Chairman | Luis Taruc |

| Vice-Chairman | Casto Alejandrino | |

At the advent of this conference, several armed groups were immediately organized and began operating in Central Luzon. A significant event was on March 13, 1942, when a squadron headed by Felipa Culala (alias Dayang-Dayang) encountered and defeated Japanese forces in Mandili, Candaba, Pampanga.[4]:32 News of Culala's successful raid raised morale for resistance fighters.[8]:63

On March 29, 1942, peasant leaders met in a forest clearing located in Sitio Bawit, Barrio San Julian, at the junction of Tarlac, Pampanga, and Nueva Ecija to form a united organization. Hukbong Bayan Laban sa mga Hapon was chosen as the name of the organization. After the meeting, a military committee was formed with Taruc (Supremo), Castro Alejandrino (Vice Commander), Bernardo Poblete (Tandang Banal), and Culala as members.[9] The Hukbalahap high command was also joined by the military commissariat; a party apparatus that provided guidance to the Huks.[4]:32

The CLB was regarded as the "wartime version of the PKP".[4]:31 While PKP officials did assume important positions in the Huk structure, the movement encompassed more that simply members of the PKP and its affiliated organizations.[8]

Robert Lapham reports either Luis Taruc or Casto Alejandrino met with Col. Thorpe at his Camp Sanchez in the spring of 1942, and the conferees agreed to cooperate, share equipment and supplies, with the Americans providing trainers.[10]:21,128–129 However, though the Huks fought the Japanese, they also "tried to thwart United States Army Forces in the Far East guerrillas", "therefore, they were considered disloyal and were not accorded U.S. recognition or benefits at the end of the war."[10]:233

| Province | Armed Hukbalahap | Number of Squadrons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | 1944 | 1944 | |

| Bulacan | 350 | 1,000 | 10 |

| Nueva Ecija | 750 | 3,000 | 22 |

| Pampanga | 1,200 | 4,000 | 35 |

| Tarlac | 300 | 600 | 6 |

| Laguna | 100 | 300 | 2 |

| Other* | – | 100 | 1 |

| Total | 2,700 | 9,000 | 76 |

| *Special squadron (Squadron 48) had no particular province. | |||

After its inception, the group grew quickly and by late summer 1943 claimed to have 15,000 to 20,000 active men and women military fighters and 50,000 more in reserve. These fighters' weaponry was obtained primarily by stealing it from battlefields and downed planes left behind by the Japanese, Filipinos and Americans.[6]:37 They fought Japanese troops, worked to subvert the Japanese tax-collection service, intercepted food and supplies to the Japanese troops, and created a training school where they taught political theory and military tactics based on Marxist ideas. In areas that the group controlled, they set up local governments (Sandatahang Tanod ng Bayan, Barrio United Defense Corps) and instituted land reforms, dividing up the largest estates equally among the peasants and often killing the landlords. In some cases, however, landlords were welcomed as participants in Huk resistance, swayed by anti-Japanese sympathies.[6]:38 PKP organizers quickly went to work to set up BUDCs in Huk controlled barrios, which contributed to its success as a resistance army,[4] although in reality there was an overlap between independently formed barrio governments, "neighborhood committees" set up by the Japanese, and BUDCs.[8]

The Huk movement was notable for its inclusion of women peasants, who advocated for inclusion in the movement in resistance to word of Japanese war atrocities against women, including rape and mutilation. Many of these women fought, but the majority of the resistance remained in villages, collecting supplies and intelligence.[6]:41 Women in the forest camps were forbidden from entering combat,[6]:52 but often trained in first aid, communication/propaganda, and recruitment tactics.[6]:50

The Huks enjoyed early successes with their continuous attacks, aimed at raising morale through quick successes as well as to acquire weapons for the severely unarmed group. The Japanese conducted two counterattacks against the Huks, on September 6 and December 5, 1942. Both attacks did nothing to dampen the frequency of Huk raids, and only served to intensify Huk operations. On March 5, 1943, the Japanese struck the Huk headquarters in Cabiao, Nueva Ecija in a surprise attack. A large number of CPP cadres and Huk soldiers were captured during the raid. By the end of the war, the Huks had 1,200 engagements, and inflicted some 25,000 enemy casualties. The Huks' strength consisted of 20,000 fully armed regulars and some 50,000 reservists.[4]

Relationship with other guerrillas

The Hukhbalahap's methods were often portrayed by other guerrilla leaders as terrorist; for example, Ray C. Hunt, an American who led his own band of 3000 guerrillas, said of the Hukbalahap that[11]

My experiences with the Huks were always unpleasant. Those I knew were much better assassins than soldiers. Tightly disciplined and led by fanatics, they murdered some Filipino landlords and drove others off to the comparative safety of Manila. They were not above plundering and torturing ordinary Filipinos, and they were treacherous enemies of all other guerrillas (on Luzon).

However, the Hukbalahap claimed that it extended its guerrilla warfare campaign for over a decade merely in search of recognition as World War II freedom fighters and former American and Filipino allies who deserved a share of war reparations.

Post-war and rebellion

The end of the war saw the return of American forces in the Philippines. While the Hukbalahap expected to have their war efforts recognized and be treated as allies,[12] the Americans, with the help of USAFFE guerillas and former PC members, forcibly disarmed Huk squadrons while charging other guerrillas of treason, sedition, and subversive activity, leading to the arrests of Luis Taruc and Casto Alejandrino in 1945, as well as incidents such as the massacre of 109 Huk guerrillas in Malolos, Bulacan.[8]

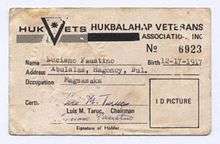

On September 1945, President Sergio Osmeña released Taruc, Alejandrino, and other Huk leaders from prison. The PKP, through Huk leaders, then formally disbanded the movement and formed the Hukbalahap Veterans' League in an effort to get the Hukbalahap recognized as a legitimate guerrilla movement. Alejandrino was its nominal chairman.[4]

In 1946, peasants in Central Luzon backed members of the Democratic Alliance in that year's election, with six candidates eventually winning seats in the Senate. Among these candidates was Luis Taruc. However, they were blocked from sitting in Congress by the government, which only exacerbated negative sentiment among the peasants in Central Luzon. The new Roxas administration attempted a pacification program, with help from Taruc, Alejandrino, Juan Feleo, and other representatives. They would be accompanied by MP guards and government officials to try and pacify peasant groups, however this did not result in any sort of success. Within days of the so-called "truce", violence once again erupted in Central Luzon. Taruc and others claimed that civilian guards and government officials were "sabotaging the peace process".[8]

On August 24, 1946, Feleo was stopped by a large band of "armed men in fatigue uniforms" in Gapan, Nueva Ecija. He had planned present the peasant's concerns to the Secretary of the Interior Jose Zulueta, before he was taken and killed. Thousands of Huk veterans and PKM members were sure that Feleo was murdered by landlords, or possibly the Roxas administration itself.[8] The incident led to Taruc joining the peasants and re-igniting the insurrection. The Roxas administration then outlawed the Hukbalahap on March 6, 1948.[4]

In 1949, Hukbalahap members ambushed and murdered Aurora Quezon, Chairman of the Philippine Red Cross and widow of the Philippines' second president, Manuel L. Quezon, as she was en route to her hometown for the dedication of the Quezon Memorial Hospital.[13] Several others were also killed, including her eldest daughter and son-in-law. This attack brought worldwide condemnation of the Hukbalahaps, who claimed that the attack was done by "renegade" members.[13] The continuing condemnation and new post-war causes of the movement prompted the Huk leaders to adopt a new name, the "Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan" or the "People's Liberation Army" in 1950.

Public sympathies for the movement had been waning due to their postwar attacks. The Huks carried out a campaign of raids, holdups, robbery, ambushes, murder, rape, massacre of small villages, kidnapping and intimidation. The Huks confiscated funds and property to sustain their movement and relied on small village organizers for political and material support. The Huk movement was mainly spread in the central provinces of Nueva Ecija, Pampanga, Tarlac, Bulacan, and in Nueva Vizcaya, Pangasinan, Laguna, Bataan and Quezon.

An important movement in the campaign against the Huks was the deployment of hunter-killer counter guerrilla special units. The "Nenita" unit (1946–1949) was the first of such special forces whose main mission was to eliminate the Huks. The Nenita Force was commanded by Major Napoleon Valeriano. The Nenita terror tactics which were not only committed against dissidents but also towards law-abiding people sometimes helped the Huks gain supporters as a consequence.

In July 1950, Major Valeriano assumed command of the elite 7th Battalion Combat Team (BCT) in Bulacan. The 7th BCT would develop a reputation toward employing a more comprehensive, more unconventional counterinsurgency strategy and reduced the random brutality against the civilian population.

In June 1950, American alarm over the Huk rebellion during the Cold War prompted President Truman to approve special military assistance that included military advice, sale at cost of military equipment to the Philippines and financial aid under the Joint United States Military Advisory Group (JUSMAG). On 26 Aug. 1950, in an "anniversary celebration" of the Cry of Pugad Lawin, the Huks temporarily seized Santa Cruz, Laguna and Camp Makabulos, Tarlac, confiscating money, food, weapons, ammunition, clothing, medicine, and office supplies.[5]:85–86 In September 1950, former USAFFE guerrilla, Ramon Magsaysay was appointed as Minister of National Defense on American advice. With the Huk Rebellion growing in strength and the security situation in the Philippines becoming seriously threatened, Magsaysay urged President Elpidio Quirino to suspend the writ of habeas corpus for the duration of the Huk campaign. On 18 Oct. 1950, Magsaysay captured the Secretariat, including the general secretary Jose Lava, following the earlier capture of the Politburo in Manila.[5]:90

American assistance allowed Magsaysay to create more BCTs, bringing the total to twenty-six. By 1951, army strength had increased by 60 percent over the previous year with 1,047-man BCTs. Major military offensive campaigns against the Huks were carried out by the 7th, 16th, 17th, and 22nd BCTs.

Another major effort against the Huks was Operation "Knockout" of the Panay Task Force (composed of the 15th BCT, some elements of the 9th BCT and the Philippine Constabulary commands of Iloilo, Capiz and Antique) under the command of Colonel Alfredo M. Santos. The Operation conducted a surprise attack on Guillermo Capadocia, commander of the Huk Regional Command in the Visayas, erstwhile Secretary General and one of the founders of the PKP. Santos' masterstroke was the enlistment of Pedro Valentin, a local mountain leader who knew the people and the terrain like the back of his hand. Capadocia died on Panay,[5]:98 of battle wounds, on September 20, 1952.

In 1954, Lt. Col. Laureño Maraña, the former head of Force X of the 16th PC Company, assumed command of the 7th BCT, which had become one of the most mobile striking forces of the Philippine ground forces against the Huks, from Valeriano who was now a colonel. Force X employed psychological warfare through combat intelligence and infiltration that relied on secrecy in planning, training, and execution of attack. The lessons learned from Force X and Nenita were combined in the 7th BCT.

With the all out anti-dissidence campaigns against the Huks, they numbered less than 2,000 by 1954 and without the protection and support of local supporters, active Huk resistance no longer presented a serious threat to Philippine security. From February to mid-September 1954, the largest anti-Huk operation, "Operation Thunder-Lightning" was conducted and resulted in the surrender of Luis Taruc on May 17. Further cleanup operations of guerillas remaining lasted throughout 1955, diminishing its number to less than 1,000 by year's end.

Organization

The Hukbalahap was regarded by the PKP as its "citizen's army" against the Japanese.[4]:31 It was headed by the Central Luzon Bureau, with Vicente Lava as its secretary, and a secretariat, ostensibly a party apparatus meant to keep the Huks in line with PKP ideology. There were five committees which composed the Huk structure:[6]:38

- Finance and Provisions – responsible for supplying provisions and other necessities to the guerrillas.

- Organization and Communication – responsible for coordinating the relationship between the leadership and its support base.

- Military Committee – responsible for the guerrilla's army regiments.

- Intelligence and Education – responsible for political education and information on enemy activity, and

- United Front – responsible for propaganda and mobilizing support.

The Huk military structured was modeled after the Chinese Red Army. It was composed of squads and platoons, consisting of 100 officers and men, which formed a squadron. Two squadrons formed one battalion, and two battalions formed a regiment.[4]:32 These numbers were not always followed though: For example, Squadron 8, based in Talavera, Nueva Ecija, had twelve squads, each with a dozen men.[8]:70

| Hukbalahap Organizational Structure, 1943[6]:39 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The initial force of 500 armed Huks which was organized into five squadrons had increased to a fully armed guerrilla force of 20,000 men.[6]:40 By 1944, Huk strength numbers at 76 squadrons.[8]:87 After the Cabiao raid by the Japanese, the PKP adopted a "retreat for defense" policy, which broke up squads to smaller groups of three to five men.[4]:34

In areas controlled by Huk guerrillas, the Huks organized an ad-hoc police force to keep the peace and stop looters and thieves.[8]:70 Huks also formed Sandatahang Tanod ng Bayan (Barrio United Defense Corps), which acted as neighborhood governments in support of the Huk forces in the field. These BUDC's were composed of KPMP and AMT members, which organized popular support for Huks, shielded harvest from the Japanese, and attacked Filipino collaborators; in effect, setting up protected zones and safe havens for the Huks.[6]:40 The Hukbalahap also set-up a government, composed of a President, Vice-President, Secretary, Treasurer, and five policemen. The barrio government also had three departments, with a person-in-charge leading it. One department collected intelligence information about the military, another handled communication between different barrios and Huk members, and the third arranged for supplies.[8]:73 The Hukbalahap government also performed civil tasks, such as officiating in weddings, baptisms, funerals, and issued marriage licenses and birth certificates.[8]:95

See also

- Philippine resistance against Japan

- Philippine Constabulary (PC)

- Military History of the Philippines

- List of American guerrillas in the Philippines

- Thomas Flynn (Columban priest)

- CPP–NPA–NDF rebellion

Notes

- "The Huk Rebellion". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- Jeff Goodwin, No Other Way Out, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p.119, ISBN 0-521-62948-9, ISBN 978-0-521-62948-5

- Orejas, Tonette. "Hukbalahap monument to rise in Ecija town". newsinfo.inquirer.net.

- Saulo, Alfredo (1990). Communism in the Philippines: An Introduction. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-403-5.

- Taruc, L., 1967, He Who Rides the Tiger, London: Geoffrey Chapman Ltd.

- Lanzona, Vina A. (2009). Amazons of the Huk rebellion gender, sex, and revolution in the Philippines ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299230937. Retrieved 10 September 2016. – via Project MUSE (subscription required)

- Agoncillo1990, p. 441

- Kerkvliet, Benjamin (1970). The Huk Rebellion: A Study of Peasant Revolt in the Philippines. University of California Press.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 448

- Lapham, R., and Norling, B., 1996, Lapham's Raiders, Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 0813119499

- Breuer, William B. The Great Raid: Rescuing the Doomed Ghosts of Bataan and Corregidor. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (2002)

- Weir 1998

- Martinez, p. 150

References

- Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960], History of the Filipino People (8th ed.), Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, ISBN 971-8711-06-6.

- Bautista, Alberto Manuel (1952), The Hukbalahap Movement in the Philippines, 1942-1952, University of California.

- Greenberg, Lawrence M. (1987), "V. Ramon Magsaysay, Edwards Landsdale, and the Jusmag", The Hukbalahap Insurrection: A Case Study of a Successful Anti-Insurgency Operation in the Philippines, 1946–1955, United States Army Center of Military History, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 86-600597.

- Greenberg, Lawrence M. (1987), "VI. The Insurrection – Phase II (1950–1955)", The Hukbalahap Insurrection: A Case Study of a Successful Anti-Insurgency Operation in the Philippines, 1946–1955, United States Army Center of Military History, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 86-600597.

- Manuel F. Martinez (2002). "Mission Possible:Assassinate Quezon – and Mrs. Quezon". Assassinations and Conspiracies: From Rajah Humabon to Imelda Marcos. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, Inc. pp. 138–152. ISBN 971-27-1218-4.

- McClintock, Michael (1992), "4. Toward a New Counterinsurgency: Philippines, Laos, Vietnam", Instruments of Statecraft: U.S. Guerella Warefare, Counterinsurgency, and Counterterrorism, 1940-1990, Pantheon Books.

- Valeriano, Napoleon D., "Military Operations", Counter-Guerrilla Seminar Fort Bragg, 15 June 1961 – details how the Philippine Constabulary, aided by the Scout Rangers, defeated the Huk insurgency in Central Luzon.

- Weir, Fraser (1998), "American Colony and Philippine Commonwealth 1901–1941", A Centennial History of Philippine Independence, 1898–1998, retrieved July 24, 2020

- "IV. The Rebirth of the Army", (Title unknown)

.svg.png)