Houting

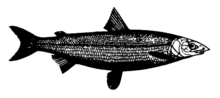

The houting (Coregonus oxyrinchus) is a European, allegedly extinct species of whitefish in the family Salmonidae. It is native to the estuaries and rivers draining to the North Sea. The houting is distinguishable from other Coregonus taxa by having a long, pointed snout, an inferior mouth and a different number of gill rakers.[1][2] The houting once occurred in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and England.[3]

| Houting | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Salmoniformes |

| Family: | Salmonidae |

| Genus: | Coregonus |

| Species: | C. oxyrinchus |

| Binomial name | |

| Coregonus oxyrinchus | |

Controversial status

There is however controversy whether whitefish surviving in the southeastern North Sea sector of Denmark (Wadden Sea) and considered there as houting (Danish: snæbel) represent the same species as the houting that was extirpated from the more southwestern parts of the North Sea.[4][5] Like the more southwestern population, the Danish North Sea population has a long, pointed snout and an inferior mouth, and it is anadromous, spending most of its adult life in coastal waters, but migrating into rivers to breed (some other European Coregonus occur in brackish water, but the ability to live long-term in full salt water is unique to the houting).[4][6]

The Danish houting is genetically part of the widespread Coregonus lavaretus complex (including Coregonus maraena of the Baltic Sea basin; some prefer to include the Danish houting in this species), while its genetic relationship to the extinct population cannot be confirmed due to a lack of sufficient samples of the latter.[4][7] Nevertheless, there are some minor differences in the genetics of the Danish houting compared to other living members in the C. lavaretus complex, as well as the differences in morphology and ecology, making it an evolutionarily significant unit.[4][7][8] Hybridization and introgression between North Sea houting and its relatives is well-documented, and likely the result of translocations of Coregonus between different regions by humans.[8] Some researchers argue that the morphological differences between different houting populations are not exceptional within the broader variation of the European whitefish, and probably no species-level extinction has taken place.[4][9] The primary reason for treating the Danish houting and the extinct houting as separate are differences in the number of gill rakers (on average, the Danish has fewer than the extinct), but this number can vary extensively in Coregonus, even within a single population and species,[6][10] and genetic studies of Coregonus have shown that gill rakers are of limited use in predicting relationship among populations.[11][12] Some think that the morphological differences in number of gill rakers are sufficient for treating them as separate, and that the last true houting was caught in the lower Rhine in 1940.[1][3] Studies in the early 2000s (decade) indicated that there was no overlap in the possible number of gill rakers of the two (28–35 in the Danish; 38–46 in the extinct),[1][2] but later reviews have shown that there is an overlap (up to 41 has been found in the Elbe, a reintroduced population based on Danish houting).[13]

A €13 million restoration project of the Danish houting, partly funded by the European Union's LIFE programme and the Danish Natural Agency, was undertaken in 2005–2013,[14][15] and there is ongoing monitoring of the species and regulation of the fish-eating great cormorant from important locations.[16] As of 2019, a total of more than €20 million has been used on its conservation, with almost two-thirds funded by Denmark and the remaining by the European Union.[17] However, the only remaining fully natural and significant population of Danish houting is in the Vidå River, estimated in 2014 to consist of about 3,500 adults. Little is known about its exact spawning and juvenile requirements, and despite the earlier project it was still declining, leading to fears that it could become fully extinct unless more is done to preserve it.[16] After years with a downward trend in its numbers, an increase to about 4,000 adult Danish houtings was registered in 2018–19, with most individuals in the Vidå and fewer in Ribe River (both populations increasing).[17]

Individuals from the Danish population have been used as a basis for re-establishing houting in the Eider, Elbe (both indisputably a natural part of the range) and Rhine (arguably non-native, if the extinct is recognized as a separate species).[13][18][19]

References

- Freyhof, J. and C. Schöter. 2005. The houting Coregonus oxyrinchus (L.)(Salmoniformes: Coregonidae), a globally extinct species from the North Sea basin. Journal of Fish Biology 67:3, 713–729.

- Schöter C., 2002. Revision der Schnäpel und Großen Maränen des Nordseeund südwestlichen Ostseeraumes (Teleostei: Coregonidae). Diplomarbeit, Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn.

- Freyhof, J. & Kottelat, M. 2008. Coregonus oxyrinchus. In: IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 21 December 2008.

- Hansen M.M., Fraser D.J., Als T.D. & Mensberg K.L.D.(2008). Reproductive isolation, evolutionary distinctiveness and setting conservation priorities: The case of a European lake whitefish and the endangered North Sea houting (Coregonus spp.). BMC Evolutionary Biology 8:137 doi:10.1186/14716-2.

- Maas, P.H.J. (2010). Houting – Coregonus oxyrinchus Archived 2010-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. In: TSEW (2014). The Sixth Extinction Website. Downloaded on 29 June 2014.

- Møller, P.R.; and H. Carl, editors (2012). Atlas over danske ferskvandsfisk [Atlas of Danish Freshwater Fish]. Natural History Museum of Denmark ISBN 9788787519748.

- Jacobsen M.W.; Hansen M.M.; Orlando L.; Bekkevold D.; Bernatchez L.; Willerslev E.; and Gilbert M.T. (2012). Mitogenome sequencing reveals shallow evolutionary histories and recent divergence time between morphologically and ecologically distinct European whitefish (Coregonus spp.). Mol Ecol. 21(11): 2727-2742. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05561.x

- Dierking, J.; L. Phelps; K. Præbel; G. Ramm; E. Prigge; J. Borcherding; M. Brunke; and C. Eizaguirre (2014). Anthropogenic hybridization between endangered migratory and commercially harvested stationary whitefish taxa (Coregonus spp.). Evol Appl. 7(9): 1068-1083. doi:10.1111/eva.12166

- Vinter, H.V. (2017). Taxonomische status van houting in Nederlandse wateren. [Taxonomic status of houting in waters of the Netherlands]. Wageningen University & Research Rapport C115/17.

- Christensen, G.H. (2010). Danmarks ferskvandsfisk [Denmark's Freshwater Fish]. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-87-02-07893-0

- Østbye K.; Bernatchez L.; Naesje T.F.; Himberg K.J.; and Hindar K. (2005). Evolutionary history of the European whitefish Coregonus lavaretus (L.) species complex as inferred from mtDNA phylogeography and gill-raker numbers. Mol Ecol. 14(14):4371-4387. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02737.x

- Ozerov, M.Y.; M. Himberg; T. Aykanat; D.S. Sendek; H. Hägerstrand; A. Verliin; T. Krause; J. Olsson; C.R. Primmer; and A. Vasemägi (2015). Generation of a neutral FST baseline for testing local adaptation on gill-raker number within and between European whitefish ecotypes in the Baltic Sea basin. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 28(5): 1170–1183. doi:10.1111/jeb.12645

- Ramm, G.; and J. Dierking (2014). North Sea and Baltic houting - Gill raker morphometric differentiation between populations of the endangered fishes North Sea and Baltic houting. Geomar, Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel.

- The houting project – The second largest nature restoration project in Denmark naturstyrelsen.dk (the Danish Nature Agency)

- Snæbelprojekt – Naturgenopretningsprojekt for en af EU's mest truede fiskearter Archived 2014-05-03 at the Wayback Machine naturstyrelsen.dk (the Danish Nature Agency)

- Svendsen, J.C.; A.K.O. Alstrup; and L.F. Jensen (11 April 2018). Save a North Sea fish from becoming museum piece. Nature. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- Mandrup, L., and N.M. Jørgensen (26 April 2019). Efter redningsaktioner for 150 mio. kr.: Danmarks mest sjældne fisk er i lille fremgang. [After rescue projects for 150 million DKK: The population of Denmark's rarest fish is slowly increasing]. DR News. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- Borcherding, J.; M. Heynen; T. Jäger-Kleinicke; H. V. Winter; and R. Eckmann (2010). Re-establishment of the North Sea houting in the River Rhine. Fisheries Management and Ecology 17(3): 291–293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2400.2009.00710.x

- Borcherding, J.; A. W. Breukelaar; H. V. Winter; and U. König (2014). Spawning migration and larval drift of anadromous North Sea houting (Coregonus oxyrinchus) in the River IJssel, the Netherlands. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 23(2): 161–170. doi:10.1111/eff.12058