Hospital de los Venerables

The Hospital de los Venerables (officially the Hospital de Venerables Sacerdotes, Hospital of Venerable Priests, popularly known as the Hospital of the Venerable) of Seville, Spain, is a baroque 17th-century building which served as a residence for priests. It currently houses the Velázquez Center, dedicated to the famous painter Diego Velázquez. It is located in the Plaza de los Venerables, in the center of the Barrio de Santa Cruz and close to the Murillo Gardens, the Seville Cathedral and Alcázar.

| Hospital de los Venerables | |

|---|---|

Main facade of the hospital/Centro Velasquez | |

| Type | Charity hospital and exhibition center |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 37.3851°N 5.9900°W |

| Built | 1675 |

| Architect | Juan Domínguez & Leonardo de Figueroa |

| Architectural style(s) | Baroque |

| Owner | Fundación Focus-Abengoa |

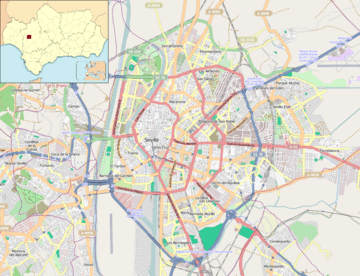

Location of Hospital de los Venerables in Seville | |

History

In 1627, the Brotherhood of Silence (Sevilla) decided to provide for elderly, poor and disabled priests. They rented a house where the priests were given shelter and assistance. In 1673, the brotherhood decided to build a new shelter for the same purpose; this was the Hospital de los Venerables.

The hospital was founded by Canon Justino de Neve in 1675, to be the residence of the venerable priests. Construction began that year, under the direction of the architect Juan Domínguez. In 1687, the project was taken over by the architect Leonardo de Figueroa who completed the building in 1697. The church was built in 1689, and is dedicated to San Fernando. The hospital was funded by the brotherhood, charity and the monarchy until 1805 when it could no longer be adequately supported.

In 1840, the hospital became a textile factory, and the former residents were moved to the Charity Hospital. Complaints from the brotherhood led to a Royal Order in 1848, which returned their property and allowed the priests to return to their old home. The Plaza de los Venerables has been named after the priests since 1868.

Residential building

The building is in the Baroque style with two floors. The hospital ceased to be a residence in the 1970s.

Cloister

The hospital has a Seville courtyard with a stepped central fountain with circular steps that are decorated with tiles. Around the courtyard are galleries with Tuscan arches on marble columns with ática bases. The fountain was designed by Bernardo Simón de Pineda and built by Francisco Rodríguez, the tiles on the fountain were made by Melchor Moreno.

The east side of the courtyard was the infirmary. It is a rectangular hall with central arches, the arches are decorated with symbols that relate to the invocation of the Hospital of San Pedro. The stairway is covered by an elliptical vault that is decorated with Baroque plasterwork.

Upstairs there is another living area, identical to the one on the ground floor, which connects to the church choir. The library is also on the upper floor. In the southeast corner is the top lookout tower which is decorated in Mudejar style. The building facade is white lime contrasting with red brick pilasters, architraves and cornices.

Church

.jpg)

The church has a single nave covered by a barrel vault with lunettes and arches. The nave is decorated with mural frescos by Valdes Leal: frescos in the chancel represent the invention of the Holy Cross; on the right side of the presbytery is represented San Fernando delivering the mosque to the Archbishop; on the left side is shown San Fernando before the Virgin of Antigua. The reliquary urns are copper and Flemish in origin. Marble paintings of the Immaculate Virgin and Child were made by Sassoferrato. The paintings that cover the vault and the walls were made by Lucas de Valdés, son of Leal.

The main altarpiece, dating from 1889, depicts the Apotheosis of San Fernando, also by Lucas de Valdés. On either side are represented San Clemente and San Isidoro, painted by Virgilio Mattoni The relief figures of John the Baptist and San Juan Evangelista are attributed to Martinez Montanes and date from the first half of the seventeenth century. The central panel of the altarpiece, which depicts St. Jerome, was originally attributed to Herrera the Elder (16th century), but later was found to date from the mid-seventeenth century. Sculptures of San Fernando and San Pedro, located under the choir, were created by Pedro Roldan.

In the altarpiece of the Conception, the figure of San Esteban is an anonymous work of the seventeenth century, but it is attributed to Montanes. The altars are the work of Juan de Oviedo. The pulpit, made with polychrome marble and rich woods is the work of Francisco de Barahona. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, who was a friend of Justino de Neve, also painted a work for the hospital, La Inmaculada de Soult, one of his most famous works, today set out in the Prado of Madrid.

Restoration

Since 1991, the hospital has been the home of the Focus-Abengoa Foundation (Fondo de Cultura of Seville). The foundation restored the building between 1987 and 1991, a process that required the authorization of Cardinal Carlos Amigo Vallejo. The building was inaugurated by Queen Sofia on November 5, 1991, with an exhibition dedicated to Sevillian painting of the Golden Age.

Velázquez Centre

The Velázquez Centre is an exhibition center that began in July 2007 with the acquisition, by the Focus Foundation, of a painting of Santa Rufina that is attributed to Diego Velázquez and valued at 12.4 million euros.[1] Some of the hospital rooms have been renovated to exhibit the Santa Rufina and others in the permanent collection. There are about a dozen works of art including the Imposición de la casulla a San Ildefonso by Velázquez and the Portrait of Martínez Montañés (1616) by Francisco Varela, both owned by the City of Seville. The Focus-Abengoa Foundation has provided another canvas attributed to Velázquez, an Immaculate Conception from the early seventeenth century. Other artists represented are Francisco Pacheco, Murillo and Bartolomeo Cavarozzi.

References

- "Sevilla stays with the canvas' Santa Rufina "by Velázquez" (in Spanish). 2007-07-04.

External links

- Velázquez Centre - Focus-Abengoa Foundation