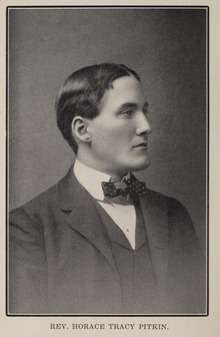

Horace Tracy Pitkin

Horace Tracy Pitkin (1869–1900) was a missionary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions who was killed in China during the Boxer Uprising in 1900. Yale China Mission, (now the Yale-China Association), was founded in his memory.[1]

Early life and decision for China

Pitkin was born in Philadelphia. On his mother's side, he was a descendant of Elihu Yale, the founder of Yale College. The Pitkin family settled in Manchester (Connecticut). Entering Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1884 Pitkin took a leading role in the campus Christian Endeavor movement. Entering Yale in 1888, he excelled in music, writing, and volunteer activities. He was widely admired for his sunny disposition and strong convictions.[1]

In the summer of 1889 at Dwight L. Moody's Northfield (Massachusetts) School, he signed the Student Volunteer Movement (SVM) pledge, indicating his intention to become a missionary. Following graduation from Yale in 1892, he entered Union Theological Seminary, New York, then spent an interim year as traveling secretary for the SVM. In 1894, with his fiancee, Letitia Thomas, a graduate of Mount Holyoke College, Massachusetts, he offered himself for service with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.[1][2]

Work in China and death

Pitkin graduated from Union Theological Seminary in 1896, then he and Letitia were married. The couple sailed from New York in November 1896, traveled through the Holy Land, Egypt, and India before landing at Tianjin in May 1897. At Baoding, in present-day Hebei province, he joined the ABCFM mission.

During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the missionary compound in Baoding was overrun by anti-missionary and anti-foreign Chinese Boxers. Pitkin was killed and the other missionaries serving in the city were also killed or later executed. In all, fourteen Presbyterian, Congregational, amid China Inland Mission missionaries were killed at Baoding. Letitia and an infant son were in the United States when Pitkin was killed.[3]

Pitkin's death motivated several students at Yale to create an organization to send missionaries to China. One said that "Pitkin's martyrdom... made me determined to see if possible that Pitkin's sacrifice was atoned for somehow by us as Yale men." The Yale Mission in China was established in June 1901. [4]

References

- Brandt, Nat (1994). Massacre in Shansi. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815602820.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Nancy E. and Jessica C. Plumb (2001). The Yale-China Association : A Centennial History. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. ISBN 9629960184.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ketler, Isaac C. (1902). The Tragedy of Paotingfu: An Authentic Story of the Lives, Services and Sacrifices of the Presbyterian, Congregational and China Inland Missionaries Who Suffered Martyrdom at Paotingfu, China, June 30th and July 1, 1900. Revell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Speer, Robert E. (1903). A Memorial of Horace Tracy Pitkin. New York: Fleming H. Revell Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Full text online Hathi Trust.

- Ng, Peter Tze Ming (Wu Ziming) (2012), "Some Scenarios of the Impact of the Boxer Rebellion", Chinese Christianity an Interplay between Global and Local Perspectives, Leiden; Boston: Brill, ISBN 9789004225749CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Notes

- "Horace Tracy Pitkin 1869 ~ 1900," Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity Archived 2015-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Brandt (1994), p. ??.

- Chapman (2001), p. 2-3.

- Ng (2012), p. 56-57.