Horace Day

Horace Day (3 July 1909 – 24 March 1984), also Horace Talmage Day, was an American a painter of the American scene who came to maturity during the Thirties and was active as a painter over the next 50 years. He traveled widely in the United States and continued to explore throughout his life subjects that first captured his attention as an artist in the Thirties. He gained early recognition for his portraits and landscapes, particularly his paintings in the Carolina Lowcountry.

Horace Talmage Day | |

|---|---|

Pick-up Game, Chapel St., Charleston, SC | |

| Born | Horace Talmage Day July 3, 1909 Amoy (Xiamen), China |

| Died | March 24, 1984 Alexandria, Virginia |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Kimon Nicolaides, Kenneth Hayes Miller, Boardman Robinson |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | American Scene, Regionalism |

Horace Day called himself a regional painter, interested in depicting the scenery of his adopted South. The style he chose to portray the landscapes and people of the South was a brand of Romantic Realism influenced by Claude Lorrain and Jacob van Ruisdael and also by the resonances in that landscape that he perceived with the rural, subtropical landscape and colonial architecture of southern China where he spent his early years. He primarily worked outside, as a plein air painter, using quick impressionistic brush strokes to record the scene.

Biography

Horace Talmage Day was the eldest of four children born in Amoy (now Xiamen), China of American missionary parents during their service with the American Reformed Mission in Fukien Province, China. The mission had bases of operation in Amoy and in Fuchow.[1] Mission families in Amoy resided in the foreign enclave on the island of Gulangyu in Amoy harbor, an urban area that has become known for its Nineteenth Century colonial architecture. In Fuchow, the mission families were situated closer to the area's peasant villages. The Day family served in both locations.

By the age of twelve, Day was painting quite accomplished landscapes of south China scenes in both oil and watercolor.[2] One of his most cherished books on art was a book on the drawings of Claude Lorrain that he acquired as a teenager, before he began his studies at the Art Students League of New York. These early inspirations are reflected in the work done by Day throughout his career.[3]

Following his graduation from the Shanghai American School in 1927, Day came to the United States to study at the Art Students League of New York. While there, he studied with, Kimon Nicolaides, Boardman Robinson, and Kenneth Hayes Miller, later serving as an assistant to Nicolaides.[4] One of his drawings was selected to illustrate an exercise in the classic work by Nicolaides, The Natural Way to Draw, that was assembled by Nicolaides’ students following his premature death.[5]

Day's promise as a painter was immediately recognized at the Art Students League. He was awarded summer fellowships by the Tiffany Foundation while studying at the Art Students League and exhibited in every Tiffany Annual Exhibition during the years 1930-33. The first inclusion of Day's work in a national exhibition dates from 1931, when his work was included in an international exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. From 1933 until his military service in World War II, Day was represented by the Macbeth Gallery in New York – one of the major commercial venues of the time.[6]

Day's work gaining recognition included portrait studies, floral still lifes, urban scenes and rural landscapes of subjects in New York, Vermont, Georgia and the Carolina Lowcountry.[7] He continued to explore each of these subjects through the balance of his life. Examples of such work are in public and private collections, including the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the New Britain Museum of American Art, the Gibbes Museum of Art, the Robert Hull Fleming Museum, the Addison Gallery of American Art, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and the Morris Museum of Art.[8]

Following completion of Day's studies at the Art Students League, Day was named artist-in-residence at the Henry Street Settlement in New York. Founded by Lillian Wald, the Henry Street Settlement was in that period one of the pivotal centers of creative energy in New York. In 1936, Day was named the first director of the Gertrude Herbert Institute of Art in Augusta, Georgia.[9] During that period, he first discovered the landscape of the Carolina Lowcountry while continuing to paint in Vermont.

In 1941, Day married the artist, Elizabeth Nottingham, who had also studied at the Art Students League of New York, and the two joined the faculty of Mary Baldwin College. Except for time on leave for military service, during which Day continued to paint, and a one-year visiting appointment at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1946-47 with their friend Edward Lanning, Day thereafter was a Professor of Art at Mary Baldwin until his retirement in 1967.[10]

The Days taught jointly at Mary Baldwin College until the death of Elizabeth Nottingham in 1956. Favored venues during this period were Vermont, West Virginia, the rugged landscape of southwest Virginia, particularly the cliffs at Eggleston on the New River in Giles County, a subject that Day painted repeatedly over a period of 30 years, and the Carolina Lowcountry, especially Edisto Island. Both artists preferred to paint outdoors and directly from nature; and both were equally skilled in watercolor, ink, and oils.[11] At the time of Elizabeth Nottingham's death, she was also gaining significant national recognition.[12]

For the last seventeen years of Day's career, between 1967 and 1984, Day was an Alexandria, Virginia, resident. While continuing to travel widely, in the American West and the South, Day produced a number of paintings of city life in Old Town Alexandria, portraits of black and white Alexandrians of the period, nearby landscapes, gardens of Alexandria's historic houses and still lifes. Even though painted comparatively recently, it was observed when the work was exhibited in 2003 that while the work in aggregate captured an image of Alexandria in transition, the paintings were linked in some ways more closely to the South of 50 years before than to contemporary life.[13]

Day at work

The great tradition

Day viewed himself as an artist working in the great tradition of the old masters, with a distaste for bravura or sentimentality. An early critic noted that Day felt that “a painter’s methods should be concealed rather than flaunted,” that he believed “that an enthusiasm for his subject [was] the surest escape from self-consciousness and its consequent mannerisms.”[14] Artists, Day said, “are in one sense craftsmen handing down their methods to be reinterpreted by each succeeding generation.”[15]

Writing later, at a time when Abstract Expressionism and its associated celebration of artistic personality was enjoying its heyday, Day agreed that “style is indivisible with the personality of the artist”, but contended that style “was to be achieved through a long apprenticeship with appearances, perception growing as the painter learns to divine the inherent order about him.”[16] Quoting Matisse, Day maintained that when an artist paints, the artist “must feel that he is copying nature. Even when he consciously departs from nature he must do it with the conviction that it is only better to interpret her.”[17]

Near the end of Day's life, another critic summed up Day's career and the breadth of his work, writing. “He lavishes a brilliant technique on … interpretations of nature as he observes it, always at first hand. Day’s work celebrates the delights of seeing, and his … sight embraces a variety of subjects that can be attempted by few painters. Equally at ease with landscape, portraits, still-life and figures, Horace has worked in the conviction that the age of great painting continues in our time.” [18]

A sense for color

Very early in Day's career, a prominent critic of the time noted Day's exceptional sense for color and skill in handling color in both oil paintings and watercolor. “The best of Mr. Day’s landscape is notable for his handling of color in achieving his effects. In his oils it reaches depths and has a resonance that is a part of all great work in that medium. In his water-colors it is often softened to delicate nuances that testify to his sensitiveness – the envelope of this earth, the form that furnishes the foundation of his design.”[19] In commenting on Lefevre’s Quarry (1937), a painting of an abandoned marble quarry in Vermont that is now in the collection of the Fleming Museum, he observed, “Without the skillful use of fine color it would have been quite impossible to invest with aesthetic interest and value such a subject. Here the thing itself – the quarry – is almost entirely hidden in a symphony of the greens of luxuriant foliage which awaken spiritual and emotional reactions entirely apart from and infinitely more important than any representation of such a forgotten hole in the ground.”[19]

Day's “masterful command of color” and “ability to imbue his paintings with vibrant energy” was likewise marked in Day's later work. In addition, compared with his earlier paintings, Live Oak, Beaufort, South Carolina (1938),[20] Day's later paintings show his confidence as a mature artist in their loose and expressive brushwork.[21]

Bodies of Work

Lowcountry landscape

Day's introduction to the Carolina Lowcountry in 1936 occurred at the height of the artistic movement now known as the Charleston Renaissance.[22] Over the next 50 years, Day carried this tradition into the late 20th century with works such as Athenian Room I (ca. 1980) and Kaye’s Drug Store, King Street, Charleston, SC (ca. 1980), depicting meeting places central to the daily lives of Charlestonians.[20]

Deeply influenced by the resonances of the Lowcountry landscape with the China of his childhood, he soon began to create from this quite different perspective images of the Lowcountry that emphasized the vernacular architecture and lush, tropical vegetation and not simply its grand antebellum mansions. “I see beauty in Charleston in places where many people would never dream of discovering it,” he once said.[23] The spirit of the country was to be found, Day believed, “not simply in elegant antebellum homes, but also in the simple cabins found in the city and countryside.”[24]

Day once wrote of the Lowcountry, “The landscape here is so luxuriant that it reminds me of South China.”[25] In fact, early landscapes from this period like Live Oak, Beaufort, SC (1938)[26] have been observed to bear a striking resemblance to View from Chang Chow City Wall, Fukien Province, China (1920), a painting Day executed while still living in China. The connection he perceived fueled Day's desire to visit repeatedly and paint in the Lowcountry for the remainder of his career.[9]

In the Lowcountry as elsewhere, Day worked en plein air to capture directly the color and intensity of the scene. As a result of that direct, emotional connection, Day's paintings have been acclaimed for revealing the essence of their place and the spirit of their people, and the sensitivity with which he recorded their character and the architecture of their homes, “whether simple wooden cabins set in a spreading field or pillared mansions overhung with majestic trees.”[27]

In connection with an exhibition of his work at the Gibbes Museum in 2004, Day was acclaimed as having "captured the architecture, landscape and people of the area through charming, sensitive renderings in watercolor and oil, including Church, Edisto Island, SC (1960) and Live Oak Avenue, Edisto Island, SC(1960)." Both paintings, it was remarked, demonstrate Day's "masterful command of color and the ability to imbue his works with vibrant energy and a solid sense of place."[25]

Murals

In response to a growing interest in mural painting, Day joined the Beaux Arts Mural Group in New York City. In 1940, he applied to the Treasury Department's Section of Painting and Sculpture for a commission to do a mural for a United States Post Office. He was awarded a commission for the post office in Clinton, Tennessee. The mural, entitled Farm and Factory, was installed by June 12, 1941. Day executed the mural in casein tempera paint, building up its surface with thin layers of color. Using that technique, Day produced a painting that is light and airy with colors that seem objective. In 1989, when Clinton acquired a new, larger post office, Day's mural was transferred to its main interior.[28]

World War II

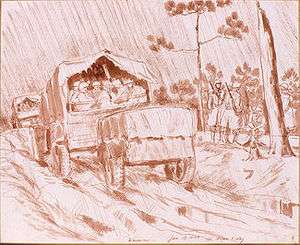

When Day was drafted in late 1942, he was slated to become part of an Army war artists program.[29] After that program was killed by Congress in early 1943,[30] Day served with the Army Medical Corps as a soldier draftsman/cartographer (311 Medical Battalion, 86th Division) with no formal responsibilities as an artist. He served from 1943–45, with duties including driving ambulances and tending the wounded. Early in his military service, he began drawing and painting sketches, watercolors and oil paintings from the point of view of an enlisted soldier. During his military training, he also executed a six-panel mural of camp life for the music room of the enlisted men's recreational center on the Camp Howze Army Base in Texas.

In 1944, three of his oil paintings. Suspicion of Gas, K.P., and Reveille in Bivouac, were included in the exhibition, Art in the Armed Forces, at the National Gallery in London.[31] In 1945, two of the works, Maneuvers in January, a drawing; G.I. Country Club, an oil on paper, were included in the 1945 Annual Exhibition of Watercolors, Prints, Drawings and Sculpture at the Whitney Museum.[32] In the years immediately following the war, more comprehensive exhibitions of this body of work were mounted by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.[33] In 1975, the murals and nearly a hundred drawings and paintings were exhibited at the Alexandria Athenaeum as its opening exhibition of that season.[34] Day's service club murals are among the very few murals of their kind to survive the war and are now in the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University.

Portraits of African Americans

From the beginning of Day's career, he chose to do portraits and portrait studies of persons whom he found interesting subjects, in addition to formal commissions. Like his other work, Day's portraits were done from life. When an early group of portraits of children from the Henry Street Settlement were included in an exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in 1937, the portraits were singled out for their good humor and depth of perception.[35] Day continued to do drawings, watercolors, and oil portraits of his fellow soldiers while serving in the Army.[36]

Notable among Day's portraits and portrait studies are numerous portraits of African-Americans many of whom he met on the street while painting. At a time when African-Americans harbored insecurities about their skin color, Day with an artist's eye saw beauty in the variety and tonal richness of black skin. In connection with one recent exhibition[37] of these portraits that explored issues of style and identity as expressed by African-Americans in Alexandria, Virginia, during the 1970s, Adrienne Childs observed that "Horace Day demonstrated a high level of consciousness of the history and politics of representing blacks, as well as the social and psychological impact that the prevailing standards of beauty had on some people of color. … In many ways, Day’s portraits of African American subject respond to the demeaning tropes of blackness that characterized the images of blacks in American art and popular visual culture through the early twentieth century" in America.”[38]

When exhibited, Day’s portraits of African Americans have been commended for their confident brush strokes and bold color combinations. In the view of some, Day’s portraits of African-Americans are his best work.[39]

Exhibitions

- 1938, Sea Island Country, Macbeth Gallery, New York, New York[40]

- 1939, New York World’s Fair, New York, New York[41]

- 1944, Art in the Armed Forces, National Gallery, London[42]

- 1949, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia[43]

- 1965, Chrysler Museum

- 2002, Horace Day and Elizabeth Nottingham: A Marriage in Art, Hunt Gallery, Mary Baldwin College, Staunton, Virginia [44]

- 2003, Horace Day: An Artist in Alexandria, 1967–1984, Alexandria Lyceum, Alexandria, Virginia[45]

- 2004, The Lowcountry Landscapes of Horace Day, Gibbes Museum, Charleston, South Carolina[46]

- 2010-2011, Style and Identity: Black Alexandria in 1970s. Portraits by Horace Day, Alexandria Black History Museum, Alexandria, Virginia[47]

Notes

- The Amoy Mission(accessed Apr. 13, 2009); Fagg, John Gerardus, Forty years in south China: The life of Rev. John Van Nest Talmage, D. D., Board of Publication of the Reformed Church in America, 1894.

- "US artist rooted in XM," Common Talk Weekly, Xiamen, China (posted 10/27/09; accessed 12/7/09) Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- Baxley, Bennett, Horace Talmage Day, 1909–1984: Resident Artist, Carolina Lowcountry, Carologue: A Publication of the South Carolina Historical Society, Winter 2001, 17, 4, 19; P. Ryan, ed., Horace Day and Elizabeth Nottingham Day: A Marriage in Art, Hunt Gallery, Mary Baldwin College (2002); U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Horace Day (1909-1984) Archived 2017-05-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- Horace Day (1909-1984) Archived 2017-05-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- Nicolaides, Kimon, The Natural Way to Draw p. 186 (1941).

- P. Ryan (2002).

- Paul Ryan (2002).

- Baxley (Winter 2001) p. 25; ____, Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC, Features Exhibit of Works by Horace Talmage Day, Carolina Arts (Dec. 2004)(partial listing of permanent museum collections with work by Horace Day); Press release Recent Morris Museum acquisition; Morris Museum Southern Collection: Cabin in Bluffton, SC. Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ____, Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC, Features Exhibit of Works by Horace Talmage Day, Carolina Arts (Dec. 2004).

- Bearss, Sara B., et al., Horace Talmage Day, Dictionary of Virginia Biography Vol. 4, Richmond, Library of Virginia (2010).

- S. Bearss (2010).

- Kuh, Katherine, Foreword: New Talent in the U.S.A., Art in America, Feb. 1956, p. 11.

- Note on 2003 exhibition at Alexandria Lyceum.

- F.F. Sherman, Note and Comment: Two Promising Young Artists, Art in America, 25, 3: (July 1937) p. 129-30.

- Id. p. 130.

- Horace Day, The Camera's Lens and the Artist's Eye, American Artist, (June/July/August 1959) 23, 6, 78.

- Id.

- Quoted in Baxley (2001) p. 25.

- Sherman (1937) p. 129.

- ____, Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC, Features Exhibit of Works by Horace Talmage Day, Carolina Arts (Dec. 2004)

- Id.; Dawson, Jessica, Galleries, Washington Post, April 24, 2003, p. C05 (Horace Day at the Lyceum).

- Severens, Martha R., The Charleston Renaissance, South Carolina Department of Natural Resource (1998).

- Baxley (2001) p. 21.

- Quoted in Spieler, Dixonville Dates Back to Reconstruction, the Beaufort Gazette online (Mar. 30, 2003) Archived 2003-04-24 at the Wayback Machine (accessed Apr. 17, 2003); Lowery, Jacob H., Sea Island Country, Macbeth Gallery, New York, New York (1938).

- ____, Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC, Features Exhibit of Works by Horace Talmage Day, Carolina Arts (Dec. 2004).

- American Art Today; Gallery of American Art Today, New York World’s Fair. New York, National Art Society, 1939 (reproduction of “Live Oak, Beaufort, S.C.”).

- M.D., Day, Painter of the Tropical South, The Art News, XXXVII, 11 (Dec. 10, 1938) p. 17; Lowery (1938), Carolina Arts, Baxley (2001) p. 21.

- Hull, Howard, Tennessee P. O. Murals:. The Overmountain Press, Johnson City, TN (1996), pp. 26-27.

- Harrington, Peter, The 1943 War Art Program, Army History (Spring-Summer 2002), pp. 4-19.

- Harrington (2002) pp. 15-16.

- Aimee Crane, Art in the Armed Forces, Hyperion Press (1944) (reproducing exhibited works).

- Bearss, Sara B., et al. (forthcoming 2010) Horace Talmage Day.

- Note, At War with Day: One-Man Show of Oils, Watercolors and Drawings at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Art Digest, 24, 6: 26 (October 15, 1949).

- Tom Holt, A War Remembered: Paintings by Horace Day, Alexandria (Virginia) Journal, September 11, 1975.

- DeVree, Howard, A Reviewer’s Notebook, New York Times (Feb. 21, 1937); Sherman (1937) p. 129.

- Ryan, ed. (2002).

- Style and Identity: Black Alexandria in the 1970s, Portraits by Horace Day, Alexandria Black History Museum, 2010. On the Web at (last visited 11/21/11)

- Adrienne Childs, Tradition and Style: Horace Day’s Rediscovered Portraits of Black Alexandrians, Catalogue: Style and Identity: Black Alexandria in the 1970s, Portraits by Horace Day, Alexandria Black History Museum, 2010, on the Web at Archived 2012-04-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Jessica Dawson, Galleries, Washington Post, April 24, 2003 p. C05 (Horace Day at the Lyceum).

- Exhibition bulletin

- American Art Today; Gallery of American Art Today, New York World’s Fair. New York, National Art Society, 1939. Reproduction of “Live Oak, Beaufort, S.C.”

- Aimée Crane, ed., Art in the Armed Forces, Hyperion Press. (1944) Paintings from exhibition reproduced: K.P., Reveille in Bivouac, Suspicion of Gas

- Note, At War with Day: One-Man Show of Oils, Watercolors and Drawings at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Art Digest, 24, 6: 26 (October 15, 1949)

- "Press release". Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- Note on exhibition

- Carolina Arts (Dec. 2004) (visited 4/10/09)

- (visited 11/21/11)

External links

- Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, Horace Talmage Day Papers, 1929–1965 description of collection

- Brown University Library Center for Digital Initiatives, Paintings Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection (keywords “Horace Day”) Military Collection search window

- New Deal/WPA Art in Tennessee, Post Office New Deal Artwork (“Farm and Factory”, Clinton, Tennessee Mural) Tennessee New Deal Art