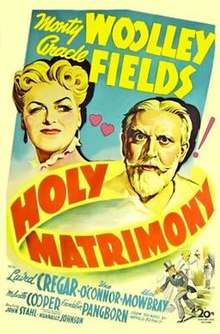

Holy Matrimony (1943 film)

Holy Matrimony is a 1943 comedy film directed by John M. Stahl and released by 20th Century Fox. The screenplay was based on the 1908 novel Buried Alive by Arnold Bennett.[4] It stars Monty Woolley and Gracie Fields, with Laird Cregar, Una O'Connor, Alan Mowbray, Franklin Pangborn, Eric Blore, and George Zucco in supporting roles.

| Holy Matrimony | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | John M. Stahl |

| Produced by | Nunnally Johnson |

| Written by | Nunnally Johnson |

| Based on | novel Buried Alive by Arnold Bennett |

| Starring | Monty Woolley Gracie Fields |

| Music by | Cyril J. Mockridge |

| Cinematography | Lucien Ballard |

| Edited by | James B. Clark |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date | August 27, 1943 |

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $709,000[1] |

| Box office | $1,250,000 (US rentals)[2] or $1.5 million[3] $1,570,700 (worldwide)[1] |

Screenwriter Nunnally Johnson was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Plot

Priam Farll is a famous English painter and recluse who has been living in various isolated places around the world with only his valet of 25 years, Henry Leek, for company. In 1905, Farll reluctantly travels to London to be knighted. Upon their arrival, however, Leek becomes very ill. Farll summons Dr. Caswell, but Leek succumbs to double pneumonia. The doctor mistakenly assumes it is Farll who has died, and the publicity-hating artist is only too glad to assume Leek's identity.

When the King himself shows up to pay his respects, Farll learns that the body is to be buried at Westminster Abbey. Trying to end the masquerade, he only manages to convince his sole relative, a cousin he has not seen since childhood, that he is a lunatic.

Farll sneaks into the funeral, but is ejected for weeping and is only saved from arrest by the arrival of Alice Chalice, a widow with whom Leek had been corresponding. It turns out that Alice had applied to a marriage bureau and had been put in touch with Leek. Since the photograph she was given shows both Leek and Farll, she too assumes that Farll is Leek. Impressed by her cheerful nature, combined with her practicality and quick thinking, he marries her and settles in Alice's comfortably large home in Putney. They are happy together.

One day, Leek's wife, Sara, and three adult sons show up to reclaim their father. Farll is unable to convince her that he is not Henry Leek without giving away his true identity to his wife. Once more, Alice saves her husband through quick thinking, pointing out that the Leeks will be disgraced by having a bigamist as a father and husband. The Leeks hastily depart. Alice herself does not care that her husband may be a bigamist.

When Alice's stock dividends are unexpectedly cut off, Farll tries to calm her worries about her mortgage by telling her that he can sell his paintings for thousands of pounds. When Alice remains unconvinced, he takes her to an art dealer to prove it, only to have the man offer him £15 for his work. Farll is outraged and leaves. Later, however, Alice reconsiders and starts selling his paintings without his knowledge.

Clive Oxford, Farll's art dealer, recognizes Farll's work, buys the paintings cheaply, and resells them for an enormous profit. One frequent buyer, Lady Vale, learns that her most recent purchase shows an omnibus that only went into service after Farll supposedly died, and takes Oxford to court for fraud. Oxford is certain Farll is still alive, tracks him down, and summons him to the trial.

Farll loathes both parties and refuses to cooperate when he is on the stand. Oxford's solicitor, Mr. Pennington, gets Farll's cousin to testify that he has two moles on his upper left chest. Farll refuses to open his shirt, but Alice does it for him, proving his true identity. Afterward, Farll and Alice move to where he can paint in blissful seclusion.

Cast

- Monty Woolley as Priam Farll

- Gracie Fields as Alice Chalice

- Laird Cregar as Clive Oxford

- Una O'Connor as Sarah Leek

- Alan Mowbray as Mr. Pennington

- Franklin Pangborn as Duncan Farll

- George Zucco as Mr. Crepitude, Lady Vale's solicitor

- Eric Blore as Henry Leek

- Ethel Griffies as Lady Vale

- Melville Cooper as Dr. Caswell

- Whit Bissell as Harry Leek

- Fritz Feld as Critic

- Cyril Delevanti as Townsman (uncredited)

- Olaf Hytten as Cockney (uncredited)

- Montagu Love as Judge (uncredited)

- Edwin Maxwell as King Edward VII (uncredited)

Production

Nunnally Johnson read the Arnold Bennett book in 1928, and was surprised no one had turned it into a film.[5] As it turned out, Johnson was incorrect. The book had been made into a film twice in the United Kingdom, and by Paramount Pictures in the United States in 1933 under the title His Double Life.[6] According to Johnson's wife, "Holy Matrimony was the picture Nunnally most enjoyed ... it was his favorite-size story, small, and the cockney wife that Gracie Fields played was Nunnally's dream wife."[7]

Rights to the book were purchased by 20th Century Fox in September 1942, and Monty Woolley was immediately cast to star in the picture.[8] On February 2, 1943, Fox announced the Gracie Fields would co-star in the picture and that the title was being changed from its working title of Buried Alive to the more audience-friendly Holy Matrimony.[9] Fox announced on March 29 that Una O'Connor and Eric Blore had been added to the cast as well.[10] The studio also said that Richard Fraser would co-star in the picture,[11] but he did not appear in the final cut of the film.

Principal photography occurred in April and May 1943. As the picture was shooting, Johnson quit his job at Fox to become an independent producer.[12] Internal studio previews of the film were so positive that Fields was offered a full contract at Fox in June 1943.[13]

The motion picture premiered in Los Angeles, California, on August 27, 1943,[14] and in New York City on September 15, 1943.[4]

Reception

Box office

The film made a profit of $267,400.[1]

Critical

Nunnally Johnson was nominated for the Oscar for Best Screenplay, but lost to Philip G. Epstein, Julius J. Epstein, and Howard Koch for Casablanca.[15]

Holy Matrimony won nearly universal praise. Bosley Crowther, writing in The New York Times, called it "a most delightful union between [Monty Woolley] and Gracie Fields", and said it was "a charming picture which is full of sly humor. And John Stahl has directed it with understanding of its smooth wit and satire." He also had strong praise for actors Cregar, O'Connor, Mowbray, and Pangborn.[16] More recent appraisals have also been very positive. Film historian Tony Thomas wrote, "The humor of Holy Matrimony stems not only from the grand performance of Monty Woolley, but also from the offbeat casting of Gracie Fields as the warmhearted wife. ... [The film is] a perfect vehicle for an actor whom nature had already typecast as a crusty highbrow."[17] Geoffrey McNab, a British film critic, called it "brilliantly scripted" in 2000.[18] Historian of LGBT culture Eric Braun said Holy Matrimony was the "most charming yet low-key comedy" of Woolley's career.[19] Film historian Peter Cowie praised Laird Cregar's "distinguished performance ... as the effeminate art dealer Clive Oxford".[20]

Legacy

The film was so successful that Woolley and Fields were reunited again two years later in the motion picture Molly and Me.[17]

The film also spawned a literary legacy. According to Gore Vidal, a subplot in Dawn Powell's novel The Wicked Pavilion is lifted directly from Holy Matrimony.[21] In 1968, the Theater Guild (an organization that commissioned plays for production off-Broadway) turned the screenplay into a musical, Darling of the Day.[22] So many changes were made to the play, however, that Johnson demanded that his name be removed from it.[5] The Musical although not a huge hit was praised for its score, by Jule Styne and E. Y. Harburg, and the performance of Patricia Routledge, who won the Tony for Best Actress in a musical. Vincent Price co-starred with her as Priam Farll.

References

- Mank, Gregory William (2018). Laird Cregar: A Hollywood Tragedy. McFarland.

- "Top Grossers of the Season", Variety, 5 January 1944 p 54

- Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century-Fox: A Corporate and Financial History Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 p 220

- "Of Local Origin." New York Times. September 15, 1943.

- Stempel, Tom. Screenwriter: The Life and Times of Nunnally Johnson. San Diego, Calif.: A.S. Barnes, 1980, p. 94.

- Kael, Pauline. 5001 Nights at the Movies. New York: Henry Holt, 1991, p. 337.

- Johnson, Nora. Flashback: Nora Johnson on Nunnally Johnson. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1979, p. 59.

- "Screen News Here and In Hollywood." New York Times. September 23, 1942.

- "Michele Morgan Will Star in Mystery Picture at Universal." New York Times. February 3, 1943.

- "Grayson, Johnson to Play in 'Tale of Two Sisters'." New York Times. March 30, 1943.

- "Fox Renews Option on Ann Rutherford's Contract." New York Times. April 20, 1943.

- Pryor, Thomas M. "News and Comment on Various Film Matters." New York Times. May 2, 1943.

- "Screen News Here and In Hollywood." New York Times. June 21, 1943.

- Leonard, William T. Theatre: Stage to Screen to Television. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1981, p. 628.

- Best American Screenplays. New York: Crown Publishers, 1990, p. 503.

- Crowther, Bosley. "Delightful Union of Monty Woolley and Gracie Fields in 'Holy Matrimony' at Roxy." New York Times. September 16, 1943.

- Thomas, Tony. The Films of the Forties. New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1975, p. 91.

- McNab, Geoffrey. Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screen Acting in British Cinema. London: Cassell, 2000, p. 92.

- Braun, Eric. Frightening the Horses: Gay Icons of the Cinema. London: Reynolds & Hearn, 2007, p. 1923.

- Cowie, Peter. Hollywood 1920-1970. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1977, p. 164.

- Vidal, Gore. The Selected Essays of Gore Vidal. Jay Parini, ed. New York: Doubleday, 2008, p. 220.

- Meyerson, Harold and Harburg, Ernest. Who Put the Rainbow in the Wizard of Oz?: Yip Harburg, Lyricist. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press, 1993, p. 331.