Hochvogel

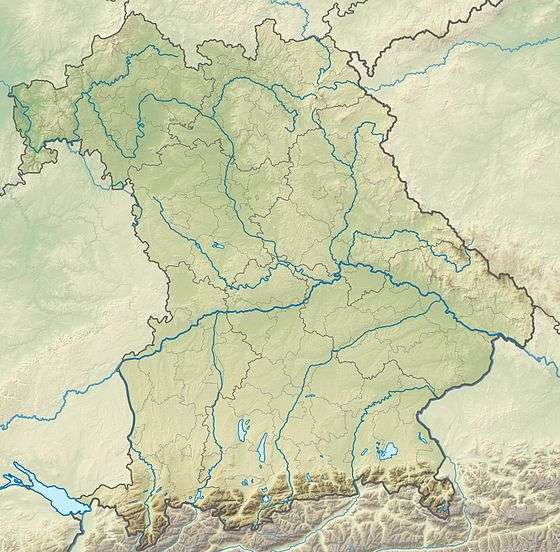

The Hochvogel is a 2,592-metre-high (8,504 ft) mountain in the Allgäu Alps. The national border between Germany and Austria runs over the summit. Although only the thirteenth highest summit in the Allgäu Alps, the Hochvogel dominates other parts of Allgäu Alps and the other ranges in the immediate neighbourhood. This is due to the fact that the majority of the higher peaks are concentrated in the central and western part of the Allgäu Alps. The Hochvogel stands on its own in the eastern part of the mountain group; the nearest neighbouring summits are 200 to 300 metres lower. Experienced climbers can ascend the summit on two marked routes.

| Hochvogel | |

|---|---|

Hochvogel | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,592 m (AA) (8,504 ft) |

| Prominence | 572 m ↓ Hornbachjoch → Großer Krottenkopf |

| Isolation | 5.4 km → Urbeleskarspitze |

| Coordinates | 47°22′52″N 10°26′14″E |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Hochvogel- and Rosszahn Group, Allgäu Alps |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Triassic |

| Mountain type | Main dolomite[1] Felsgipfel |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1832 by Trobitius |

| Normal route | Bad Hindelang – Prinz Luitpold Haus – Hochvogel |

Geology

The Hochvogel consists of main dolomite. The highest and most striking mountains in the Allgäu Alps are all made of this rock. Tectonically the Hochvogel and its main dolomite formation belong to the so-called Lech Valley Nappe (Lechtaldecke).

This rock package was overthrust over younger layers of rock during the course of Alpine mountain folding. The main dolomite is brittle in places, but forms striking rock formations in places in conjunction with the forces of erosion. The hut diary of the Prinz Luitpold Haus reports a mighty landslide on 27 May 1935 when thousands of cubic metres of rock from the southwest face crashed down into the valley.

Climbing history

The older, now out-of-print editions of the Alpine Club Guide (Alpenvereinsführer) for the Allgäu Alps state that the mountain was first climbed a long time ago. A shepherd's boy from Hinterhornbach is said to have already climbed it as early as 1767.[2] In 1818, the surveyors supposedly found a ruined cairn at the top.[3] The first ascent was at least as long ago as 1818, when the Allgäu Alps were surveyed and the Hochvogel summit was used as a triangulation point.[4] However, when a man named Trobitius from Kempten climbed the peak in 1832, some of his fellow townsfolk refused to believe him as the mountain was still considered unclimbable by many.[5]

One of the most notable touristic climbs was by Hermann von Barth, who stayed overnight at the summit in 1869. On 19 July that year he started off from Sonthofen in the morning and reached Hinterstein, travelling exclusively on foot, where he took a midday rest around 12 o'clock before continuing. Passing the Bärgündlealpe alps, the Balkenscharte saddle and the Kalter Winkel he reached the summit of the Hochvogel at around 8 o'clock in the evening. On the next day he climbed south on the eastern side of the south-southwestern arête into the Rosskar cirque and continued down to Hinterhornbach. On that day he arrived at the confluence of the Schwarzwasserbach and the Lech, where he stayed in an abandoned Alpine hut. The next day he walked via Weißenbach and the Gaicht Pass to Nesselwängle, climbed the Aggenstein and overnighted in Schattwald. On the fourth day of his great tour he returned to Sonthofen in the morning.

Conservation

The side of the Hochvogel lying on German territory, including the neighbouring mountains and valleys, is part of the Allgäu High Alps Nature Reserve. On the Austrian side there is no nature reserve near the summit. The bottom of the Hornbach valley, which borders the Hochvogel to the south, together with large parts of the Lech valley and its side valleys was designated on 1 December 2004 as the Tyrolean Lech Nature Reserve. It has an area of 41.38 km2 (15.98 sq mi).

Alpinism

Valley settlements / Bases

Hinterhornbach is the valley settlement on the southern side (in the Tyrol, Austria). Hinterstein is the village on the northern side (in the Free State of Bavaria, Germany). The approach routes from the two valleys are very different. Hinterhornbach is located immediately at the foot of the Hochvogel, its summit – admittedly not its picturesque side (Schauseite) – can be seen from the village. By contrast, Hinterstein is relatively far down the valley. The Hochvogel cannot be seen from Hinterstein or its neighbouring valleys.

On the German side there is a climber's base, the Prinz Luitpold Haus, run by the German Alpine Club. This Alpine hut may be reached from Hinterstein on the road to the Giebelhaus by bus (it is closed to private vehicles), and then on the farm track to the Bärgündletal valley and on the Alpine Club path (Alpenvereinsweg) to the hut.

Climbing

An ascent of the Hochvogel is a climbing tour with a UIAA climbing grade of I. The normal route runs from the Prinz Luitpold Haus (1,846 m (6,056 ft)) in 2½ hours over the Balkenscharte saddle and the snowfield of the Kalter Winkel to the summit. In early summer, crampons or Grödeln (= light crampons) will be needed to negotiate the said snowfield. The Kalter Winkel can be circumvented by using a partially secured climb via the Kreuzspitze, which joins the route from the Prinz Luitpold Haus above the snowfield.

Due to a widening crack at the top and imminent rockfall danger, the Bäumenheimer Weg which ran from the south, starting at Hinterhornbach in the Lechtal is closed since 2014.[6]

The out-of-print editions of the Alpine Club Guides for the Allgäu Alps also show several climbing routes. These are:

- West pillar (Westpfeiler), UIAA grade IV+

- Southwest face (Südwestwand), grade III–IV

- Northeast face (Nordostwand), grade IV+–VI−

- North pillar (Nordpfeiler), grade III

- Hochvogel east shoulder, north face (Hochvogel-Ostschulter, Nordwand), grade IV+–VI

- Hochvogel east shoulder, southwest face (Hochvogel-Nordwestschulter, Südwestgrat), grade IV

- East-northeast arête (Ostnordostgrat), grade III

- Southeast face (Südostwand), grade IV–VI

The current 16th edition of the Alpine Club Guide only contains routes up to climbing grade II. This means that in the literature today only the two normal routes to the Hochvogel are described. In 2006, however, the Allgäu-Immenstadt DAV Section put forward a DAV hut guide for the Prinz Luitpold Haus that presents the four current climbing routes on the northern side of the Hochvogel on one photograph and describes and assesses them in the text.

In the era of sport climbing, the climbing routes on the Hochvogel, which involve brittle rock and a long approach march, are rarely used.

Views

The view from the top is vast and grandiose, encompassing many of the peaks in the Allgäu Alps as well as those in the neighbouring Lechtal Alps to the south. To the east, the view extends over other chains in the Northern Limestone Alps as far as the Wetterstein and Karwendel. To the south, a panorama of the central Alpine ridge opens up from the High Tauern across the Zillertal, Stubai and Ötztal Alps to the mountains of the Albula and the Silvretta. To the west, the Swiss Alps - the Alpstein (Säntis) and the Glarus Alps (Tödi) can be seen. And, to the north, the view extends far beyond the Swabian Alps to the Black Forest and the Swabian Jura. The best views tend to occur in the autumn and winter rather than in spring and summer.

Aircraft crash

On 14 December 1945 an American Flying Fortress (a four-engine bomber) crashed on the western flank of the Hochvogel. The aircraft came from Belgium and actually intended to land at the Lechfeld Air Base. The accident killed all six crew members. their remains could not be retrieved until months later because of their location on steep slopes and heavy snow.[7]

According to the United States Air Force the accident was due to a navigation error when the aircraft flew into a snowstorm. The wreck of the machine was dismantled in the 1950s and carried away.

Gallery

Northern aspect from the Jubiläumsweg

Northern aspect from the Jubiläumsweg Southern aspect with the Kaufbeurer Haus and Hornbachtal

Southern aspect with the Kaufbeurer Haus and Hornbachtal Southern side of the summit from the Kaufbeurer Haus

Southern side of the summit from the Kaufbeurer Haus From Hinterhornbach

From Hinterhornbach

References

- Geologische Karte von Bayern mit Erläuterungen (1:500,000). Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, 1998.

- "Hochvogel.at". Hochvogel.at (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- "Heiko`s Bergtourenbuch". Wochenendaussteiger.npage.de (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- Spiehler, 1893, pp. 47-48. (in German)

- Spiehler, 1893, pp. 86-7.

- "Sperrung Bäumenheimer Weg" (in German). Deutscher Alpenverein Sektion Donauwörth. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Flugzeugabsturz am Hochvogel". www.wanderpfa.de. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

Sources and maps

- Anton Spiehler, Die Allgäuer Alpen, in Die Erschliessung der Ostalpen, Volume 1, 1893, pp. 47-48. (in German)

- Alpenvereinsführer Allgäuer Alpen 9th edition 1974, Bergverlag Rudolf Rother, ISBN 3-7633-1101-7, out of print;

- Alpenvereinsführer Allgäuer Alpen und Ammergauer Alpen alpin 16th edition 2004, Bergverlag Rudolf Rother, ISBN 3-7633-1126-2;

- Alpenvereinskarte 2/2 Allgäuer-Lechtaler Alpen – Ost 1:25,000 7th edition 2002;

- Gipfelziele Allgäuer Alpen 1987, Bruckmann Verlag, ISBN 3-7654-2095-6, out of print

- Kristian Rath und Tobias Burger, Prinz-Luitpold-Haus DAV-Hüttenführer – Wandern, Klettern, Abenteuer rund um den Hochvogel, Kempten 2006, ISBN 3-9810320-2-0.

- Wanderführer Hinterhornbach. Natur- und kulturkundlicher Wanderführer von Gustav und Georg Dinger, hrsg. v. d. Sektion Donauwörth d. Deutschen Alpenvereins, Verlag Ludwig Auer, ISBN 978-3-9807169-6-3

- Hermann von Barth, Einsame Bergfahrten, Albert Langen Verlag Munich, o.J. (description of the above-mentioned summit crossing)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hochvogel. |