History of the Boston Braves

The Atlanta Braves, a current Major League Baseball franchise, originated in Boston, Massachusetts. This article details the history of the Boston Braves, from 1871 to 1952, after which they moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin to become the Milwaukee Braves, and then eventually to Atlanta to become the Atlanta Braves. The Boston franchise played at South End Grounds from 1871 to 1914 and at Braves Field from 1915 to 1952. Braves Field is now Nickerson Field of Boston University. The franchise, from Boston to Milwaukee to Atlanta, is the oldest continuous professional baseball franchise.[2]

History

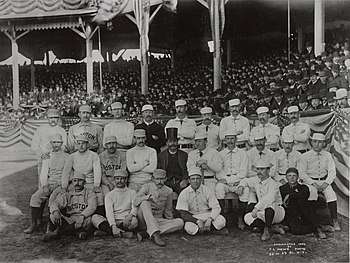

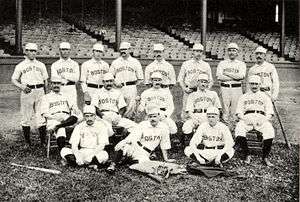

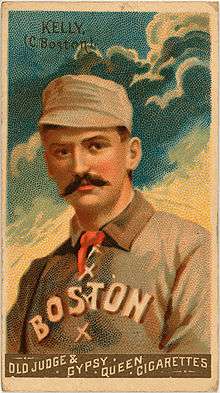

The Cincinnati Red Stockings, established in 1869 as the first openly all-professional baseball team, voted to dissolve after the 1870 season. Player-manager Harry Wright then went to Boston, Massachusetts—at the invitation of Boston Red Stockings founder Ivers Whitney Adams—with brother George and two other Cincinnati players, to form the nucleus of the Boston Red Stockings, a charter member of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. The original Boston Red Stockings team and its successors can lay claim to being the oldest continuously playing team in American professional sports.[3] (The only other team that has been organized as long, the Chicago Cubs, did not play for the two years following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.) Two young players hired away from the Forest City club of Rockford, Illinois, turned out to be the biggest stars during the NAPBBP years: pitcher Al Spalding (founder of Spalding sporting goods) and second baseman Ross Barnes.

Led by the Wright brothers, Barnes, and Spalding, the Red Stockings dominated the National Association, winning four of that league's five championships. The team became one of the National League's charter franchises in 1876, sometimes called the "Red Caps" (as a new Cincinnati Red Stockings club was another charter member). Boston came to be called the Beaneaters by sportswriters in 1883, while retaining red as the team color.

Although somewhat stripped of talent in the National League's inaugural year, Boston bounced back to win the 1877 and 1878 pennants. The Red Caps/Beaneaters were one of the league's dominant teams during the 19th century, winning a total of eight pennants. For most of that time, their manager was Frank Selee, the first manager not to double as a player as well. The 1898 team finished 102–47, a club record for wins that would stand for almost a century.

The team was decimated when the upstart American League's new Boston entry set up shop in 1901. Many of the Beaneaters' stars jumped to the new team, which offered contracts that the Beaneaters' owners didn't even bother to match. They only managed one winning season from 1900 to 1913, and lost 100 or more games six times. In 1907, the newly renamed Doves (temporarily) eliminated the last bit of red from their stockings because their manager thought the red dye could cause wounds to become infected (as noted in The Sporting News Baseball Guide during the 1940s when each team's entry had a history of its nickname(s). See details in History of baseball team nicknames). The American League club's owner, Charles Taylor, wasted little time in changing his team's name to the Red Sox in place of the generic "Americans".

When George and John Dovey acquired the club in 1907, the team earned the sobriquet Doves; when purchased by William Hepburn Russell in 1911 punning reporters tried out Rustlers. However, clever monikers did nothing to change the National League club's luck. The team adopted an official name, the Braves, for the first time in 1912. Their owner, James Gaffney, was a member of New York City's political machine, Tammany Hall, which used an Indian chief as their symbol.

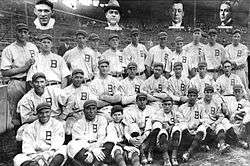

1914: Miracle

Two years later, the Braves put together one of the most memorable seasons in baseball history. After a dismal 4–18 start, the Braves seemed to be on pace for a last place finish. On July 4, 1914, the Braves lost both games of a doubleheader to the Brooklyn Dodgers. The consecutive losses put their record at 26–40 and the Braves were in last place, 15 games behind the league-leading New York Giants, who had won the previous three league pennants. After a day off, the Braves started to put together a hot streak, and from July 6 through September 5, the Braves won 41 games against only 12 losses.[4] On September 7 and 8, the Braves took 2 of 3 from the New York Giants and moved into first place. The Braves tore through September and early October, closing with 25 wins against 6 losses, while the Giants went 16–16.[5] They are the only team to win a pennant after being in last place on the Fourth of July. They were in last place as late as July 18, but were close to the pack, moving into fourth on July 21 and second place on August 12.

Despite their amazing comeback, the Braves entered the World Series as a heavy underdog to Connie Mack's Philadelphia A's. Nevertheless, the Braves swept the Athletics—the first unqualified sweep in the young history of the modern World Series (the 1907 Series had one tied game)—to win the world championship. Meanwhile, former Chicago Cubs infielder Johnny Evers, in his second season with the Braves, won the Chalmers Award.

The Braves played the World Series (as well as the last few weeks of the 1914 regular season) at Fenway Park, since their normal home, the South End Grounds, was too small. However, the Braves' success inspired owner Gaffney to build a modern park, Braves Field, which opened in August 1915. It was the largest park in the majors at the time, with 40,000 seats and also a very spacious outfield. The park was novel for its time; public transportation brought fans right into the park.

1915–1935: losing years

After contending for most of 1915 and 1916, the Braves spent much of the next 19 years in mediocrity, during which they posted only three winning seasons (1921, 1933, and 1934). The lone highlight of those years came when Giants' attorney Emil Fuchs bought the team in 1923 to bring his longtime friend, pitching great Christy Mathewson, back into the game. Although original plans called for Mathewson to be the principal owner, he had never recovered from tuberculosis that he'd contracted after being gassed during World War I. By the end of the 1923 season, it was obvious Mathewson couldn't continue even in a reduced role, and he would die two year later, with the result that Fuchs was permanently given the presidency. In 1928, the Braves traded for Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby who had a very productive year in his only season with Boston. He batted .387 to win his seventh and final batting championship.

Fuchs was committed to building a winner, but the damage from the years prior to his arrival took some time to overcome. The Braves finally managed to compete in 1933 and 1934 under manager Bill McKechnie, but Fuchs' revenue was severely depleted due to the Great Depression.

Babe Ruth to Boston Braves

Looking for a way to get more fans and more money, Fuchs worked out a deal with the New York Yankees to acquire Babe Ruth, who had, coincidentally, started his career with the Red Sox. Fuchs named Ruth vice president and assistant manager of the Braves, and promised him a share of team profits. He was also to be consulted on all player transactions. Fuchs even suggested that Ruth, who had long had his heart set on managing, could take over as manager once McKechnie stepped down—perhaps as early as 1936.[6]

At first, it looked like Ruth was the final piece the team needed in 1935. On opening day, he had a hand in all of the Braves' runs in a 4–2 win over the Giants. However, that proved to be the highest the Braves were over .500 all year. Events went downhill quickly. A 4–20 May ended any realistic chance of contention. Ruth's deterioration mirrored that of the team. While his high living of previous years had begun catching up with him a year earlier, his conditioning rapidly declined in the first month of 1935. While he was still able to hit at first, he could do little else. He could no longer run, and his fielding was so terrible that three of the Braves' pitchers threatened to go on strike if Ruth were in the lineup. Ruth soon discovered that he was vice president and assistant manager in name only, and Fuchs' promise of a share of team profits was hot air. In fact, Ruth discovered that Fuchs expected him to invest some of his money in the team.[6]

Seeing a franchise in complete disarray, Ruth retired on June 1 – only six days after he clouted, in what remains one of the most memorable afternoons in baseball history, what turned out to be the last three home runs of his career. He'd wanted to quit as early as May 12, but Fuchs wanted him to hang on so he could play in every National League park.[6] By this time, the Braves were 9–27, their season all but over. They ultimately finished 38–115, easily the worst season in franchise history. Their .248 winning percentage is the third-worst in baseball history, and the second-worst in National League history (behind only the 1899 Cleveland Spiders).

1936–1941: the Bees

Insolvent like his team, Fuchs was forced to give up control of the Braves in August 1935,[6] and new owner Bob Quinn tried to change the team's image by renaming it the Boston Bees.[7] This did little to change the team's fortunes. After five uneven years, a new owner, construction magnate Lou Perini, changed the nickname back to the Braves.

1948: National League champions

In 1948, the team won the pennant, behind the pitching of Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain, who won 39 games between them. The remainder of the rotation was so thin that in September, Boston Post writer Gerald Hern wrote this poem about the pair:

- First we'll use Spahn

- then we'll use Sain

- Then an off day

- followed by rain

- Back will come Spahn

- followed by Sain

- And followed

- we hope

- by two days of rain.

The poem received such a wide audience that the sentiment, usually now paraphrased as "Spahn, Sain, then pray for rain" or "Spahn, Sain and two days of rain", entered the baseball vocabulary. Ironically, in the 1948 season, the Braves actually had a better record in games that Spahn and Sain did not start than in games they did. (Other sources include pitcher Vern Bickford in the verse.)

The Braves lost the 1948 World Series in six games to the Indians (who had beaten the Red Sox in a one-game playoff to spoil an all-Boston World Series). This turned out to be the Braves' last hurrah in Boston.

Sam Jethroe

Acquired earlier by trade from the Brooklyn Dodgers, on April 18, 1950, Sam "Jet" Jethroe was added to the Boston Braves roster. The Dodgers had another young CF in Duke Snider rising in their system, resulting in the trade to the Braves.[8] Going on to be named National League Rookie of the Year at age 32, Jethroe broke the color barrier with Boston. In 1950, Jethroe hit .273 with 100 runs, 18 home runs and 58 RBI. His 35 stolen bases led the National League, a feat he would duplicate in 1951. While in Boston, Jethroe was roommates with Chuck Cooper, of the Boston Celtics who was the first African-American player drafted by an NBA team.[8] A former Negro League star and military veteran, Jethroe remains the oldest player to have won Rookie of the Year honors.[9][10]

Move to Milwaukee and aftermath

With the rise of Ted Williams for the Red Sox, it became clear the Braves were no longer Boston's #1 team.

Amid four mediocre seasons after 1948, attendance steadily dwindled, even though Braves Field had the reputation of being more family friendly than Fenway.

For a half century, the major leagues had not had a single franchise relocation.[11] The Braves played their last home game in Boston on September 21, 1952, losing to the Brooklyn Dodgers 8–2 before 8,822 at Braves Field; the home attendance for the 1952 season was under 282,000.[11]

On March 13, 1953, owner Lou Perini said that he would seek permission from the National League to move the Braves to Milwaukee.[12] After the franchise's long history in Boston, the day became known as “Black Friday” in the city as fans mourned the team's exit after eight decades. Perini, however, pointed to dwindling attendance as the main reason for the relocation. He also announced that he had recently bought out his original partners. He announced Milwaukee as that was where the Braves had their top farm club, the Brewers. Milwaukee had long been a possible target for relocation. Bill Veeck had tried to move his St. Louis Browns there earlier the same year (Milwaukee was the original home of that franchise), but his proposal had been voted down by the other American League owners.

Going into spring training in 1953, it appeared that the Braves would play another year in Boston. However, during a game against the New York Yankees on March 18th, the sale was announced final and that the team would move to Milwaukee, immediately.[13][14] The All-Star Game had been scheduled for Braves Field. It was moved to Crosley Field and hosted by the Cincinnati Reds.[14] The Braves franchise moved their triple-A Brewers from Milwaukee to Toledo, Ohio.[15]

After the Braves moved to Milwaukee in 1953, the Braves Field site was sold to Boston University and reconstructed as Nickerson Field, the home of many Boston University teams. The Braves Field scoreboard was sold to the Kansas City A's and used at Municipal Stadium; the A's moved to Oakland after the 1967 season.[16]

Notable Boston Braves

- Source:[17]

- Earl Averill, Boston Braves (1941), HOF (1975)

- Dave Bancroft, Boston Braves (1924–27), HOF (1971)

- Alvin Dark, Boston Braves (1946–49), ROY (1948)

- Bob Elliott, Boston Braves (1947–51), NL MVP (1947)

- Johnny Evers, Boston Braves (1914–17, 1929), HOF (1946)

- Hank Gowdy, Boston Braves (1911–1917, 1919–1923 and 1929–1930)

- Burleigh Grimes, Boston Braves (1930), HOF (1964)

- Billy Herman, Boston Braves (1946), HOF (1975)

- Rogers Hornsby, Boston Braves (1928), HOF (1942)

- Del Crandall, Boston/ Milwaukee Braves (1949-63) 11 Time All Star, Last living Boston Braves player

- Sam Jethroe, Boston Braves (1950–52) ROY (1950)

- Ernie Lombardi, Boston Braves (1942), HOF (1986)

- Al López, Boston Bees (1936–40), HOF (1977)

- Bill McKechnie, Boston Braves (1913, Manager 1930-37), HOF (1962)

- Rabbit Maranville, Boston Braves (1912–20, 1929–35), HOF (1954)

- Eddie Mathews, Boston/Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves (1952–66), HOF (1978)

- Christy Mathewson, Owner/Executive, Boston Braves (1922–25), HOF as Player (1936)

- Rube Marquard, Boston Braves (1922–25), HOF (1971)

- Johnny Sain, Boston Braves (1942-51), 3X All Star, Ace of 1948 Staff

- Joe Medwick, Boston Braves (1945), HOF (1968)

- Kid Nichols, Boston Beaneaters (1890–1901) HOF (1949)

- Babe Ruth, Boston Braves (1935), HOF (1936)

- Al Simmons, Boston Braves (1939), HOF (1953)

- George Sisler, Boston Braves (1928–30), HOF (1939)

- Billy Southworth, Boston Braves (1921–23, Manager 1946–49, 1950–51), HOF (2008)

- Warren Spahn, Boston Braves Boston/Milwaukee Braves (1942, 1946–64), HOF (1973)

- Casey Stengel, Boston Braves (1924–25, Manager 1938–43), HOF (1966)

- Ed Walsh, Boston Braves (1917), HOF (1946)

- Lloyd Waner, Boston Braves (1941), HOF (1967)

- Paul Waner, Boston Braves (1941–42), HOF (1952)

References

- Achorn, p. 24

- "BRAVES FIELD". www.ballparksofbaseball.com. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- Atlantabraves.com History

- http://www.baseball-almanac.com/teamstats/schedule.php?y=1914&t=BSN

- http://www.baseball-almanac.com/teamstats/schedule.php?y=1914&t=NY1

- Neyer, Rob (2006). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders. New York: Fireside. ISBN 0-7432-8491-7.

- Bjarkman, Peter C.; Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Team Histories: The National League, p. 35 ISBN 0887363741

- "Unheralded Jethroe broke barriers with Braves". MLB.com. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/jul/17/guardianobituaries.sport

- https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/j/jethrsa01.shtml

- Hand, Jack (March 19, 1953). "Transfer of Braves to Milwaukee viewed as first in series of future changes". Youngstown Vindicator. (Ohio). Associated Press. p. 38.

- Larson, Lloyd (March 14, 1953). "Big league ball here this year!". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 1, part 1.

- "Boston Braves go to Milwaukee". Pittsburgh Press. United Press. March 18, 1953. p. 1.

- Thisted, Red (March 19, 1953). "We're home of the Braves!". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 1, part 1.

- April 9, 1953: Braves get a wet welcome to Milwaukee, SABR (Society for American Baseball Research), Bill Nowlin, included in SABR's book From the Braves to the Brewers: Great Games and Exciting History at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, 2016.

- Lowry, Philip (2006). Green Cathedrals. Walker & Company. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8027-1608-8

- "Hall of Famers". Atlanta Braves. Retrieved 5 November 2019.