History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

The history of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) spans nearly two hundred years beginning with its founding in 1824. RPI is the oldest continuously operating technological university in both the English-speaking world and the Americas.[1] The Institute was the first to grant a civil engineering degree in the United States, in 1835.[2][3] More recently, RPI also offered the first environmental engineering degree in the United States in 1961,[4] and possibly the first ever undergraduate degree in video game design, in 2007.[5][6]

Timeline of institute events

| 1824 | Rensselaer School is established, board of trustees meet on December 29 |

| 1825 | School opens at Old Bank Place, on January 5 |

| 1826 | State of New York incorporates school |

| 1834 | Renamed the Rensselaer Institute, moving to Van der Heyden Mansion |

| 1835 | Institute confers first degree in civil engineering in the United States, to four students, a one-year C.E. Eight young women enroll in a special mathematics course[7] |

| 1841 | Institute removes back to Old Bank Place |

| 1850 | Reorganizes into a three-year undergraduate curriculum |

| 1861 | Renamed the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute |

| 1864 | Great Troy Fire destroys Infant School property |

| 1873 | Institute participates in its first ever intercollegiate sporting event, in baseball, against Union College |

| 1881 | Garnet Douglass Baltimore, first African-American at Rensselaer, earns a degree |

| 1904 | Fire destroys the Main Building |

| 1914 | Confers its first graduate degree in mechanical engineering, M.S. |

| 1916 | Confers its first doctorate in electrical engineering, D.Eng. |

| 1946 | Lois Graham and Mary Ellen Rathbun, first two women, earn a degree at the institute |

| 1951 | Reorganizes into a four-year curriculum for undergraduates |

| 1961 | Confers the first degree in environmental engineering in the United States |

| 1973 | Ivar Giaever is first alumni to win the Nobel Prize |

| 1999 | Shirley Ann Jackson elected first African-American female university president in the United States |

| 2000 | Rensselaer Plan unveiled |

Pre-RPI: The van Rensselaer Family

- see also: History of Troy, New York

In 1609, Henry Hudson, exploring for Holland, sailed up what is now called the Hudson River. His report back to Holland established a Dutch presence in the fur trade in what the "usurping Hollanders" in 1614 called "New Netherland." In 1630, Kiliaen van Rensselaer became the patroon of Rensselaerswyck, a manor 24 miles long and 48 miles wide that encompassed area within the current Albany, Rensselaer, and Columbia counties.

In 1659, Jan Barentsen Wemp, with the permission of Jan Baptist van Rensselaer and Arent van Corlaer, purchased the "Great Meadow Ground," which would become the site of the city of Troy.[8] On January 5, 1789 the freeholders in "Ashley's Ferry" and other surrounding farm areas met at Ashley's Tavern and established the name Troy for their village.

Founding

Stephen van Rensselaer III established the Rensselaer School on November 5, 1824 with a letter to the Rev. Dr. Samuel Blatchford, in which Van Rensselaer asked Blatchford to serve as the first president. Within the letter he appointed Amos Eaton as the school's first senior professor and appointed the first board of trustees. An untrue myth once circulated that the Van Rensselaer and Eaton met in prison. Amos Eaton was indeed in prison from 1810 to 1815 for forgery, but he and Stephen van Rensselaer met in 1820 when Van Rensselaer charged Eaton with surveying the land that would become the site of the Erie Canal.[9] Van Rensselaer gave Eaton permission to lecture at towns along the way, clearly a precursor to the founding of an institute of higher learning. The expressed purpose of the institute was to be "for the application of science and technology to the common purposes of life."[10]

On December 29 of 1824, the president and the board met and established the methods of instruction, which were rather different from methods employed at other colleges at the time. Students spent six hours a day performing experiments and explaining their rationale and gave their own lectures rather than listening to lectures and watching demonstrations.[11] Tuition was around $80 a semester.[11]

1825–1900

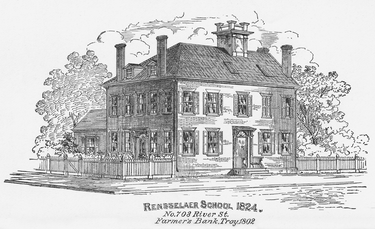

The school opened on Monday, January 3, 1825 at the Old Bank Place, a building at the north end of Troy.[12] The opening was announced by a notice, signed by the president, and printed in the Troy Sentinel on December 28. The school attracted students from New York, Massachusetts, Vermont, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The fact that the school attracted students from afar is attributed to the reputation of Eaton. Fourteen months of successful trial led to the incorporation of the school on March 21, 1826 by the State of New York. In its early years, the Rensselaer School resembled a graduate school more than it did a college. It drew graduates of older institutions such as Amherst, Bowdoin, Columbia, Harvard, Penn, Princeton, Union, Wesleyan, Williams, and Yale. Indeed, there was a considerable stream from Yale, where there were several teachers interested in the sciences.

During this period, the Rensselaer School, renamed the Rensselaer Institute in 1832, was a small but vital center for technological research. The first civil engineering degree in the United States was granted by the institute in 1835, and many of the best remembered civil engineers of that time graduated from the school. Important visiting scholars included Joseph Henry, who had previously studied under Amos Eaton, and Thomas Davenport, who sold the world's first working electric motor to the institute.[13] In 1847, alumnus Benjamin Franklin Greene became the new senior professor. Earlier he had done a thorough study of European technical schools to see how Rensselaer could be improved. In 1850 he reorganized the school into a three-year polytechnic institute with six technical schools.[14] In 1861 the name was changed to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.[15]

The great fire of 1862

One of the most well known events in Troy's early history is the Great Fire of 1862, which destroyed over 507 buildings in Troy and gutted 75 acres (300,000 m2) in the heart of the city.[16] The fire started around noon on May 10 due to sparks from a passing locomotive setting a shingle of the Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad Bridge on fire. Due to unfavorable winds, the fire spread to a broad belt of flame across the city in less than an hour and a half.[17] By six o'clock, the fire brigade stayed the spread of the fire at Donohue & Burge's carriage factory on 7th and Congress. As night fell, the view from 8th Street was still a no little grandeur. "Here and there unquenched flames illuminated desolated spaces, and great beds of fire glowed among the blackened walls of the destroyed buildings."[18]

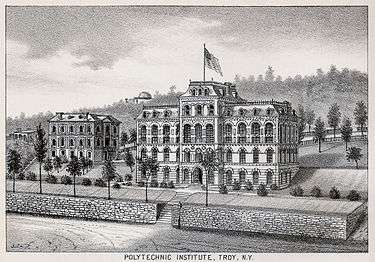

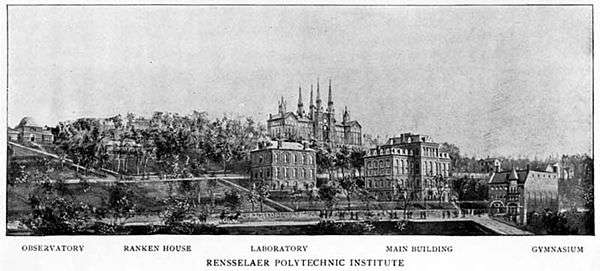

The "Infant School" building that housed the Institute at the time was destroyed in this fire. Columbia University proposed that Rensselaer leave Troy altogether and merge with its New York City campus. Ultimately, the proposal was rejected and the campus left the crowded downtown for the hillside which offered potential for expansion. Classes were temporarily held at the Vail House and in the Troy University building until 1864,[19] when the Institute moved to a building on Broadway on 8th Street, now the site of the Approach.[16]

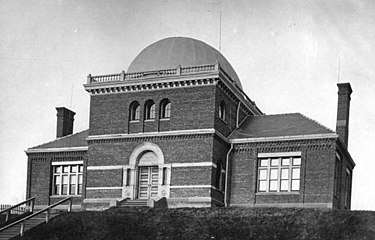

The Proudfit observatory

In 1875 Mr. and Mrs. Ebenezer Proudfit of Troy donated $15,000 to build an impressive observatory named the William Proudfit Observatory.[20] The observatory was named in honor of the Proudfit's son, an RPI student in the class of 1877 who died in a tragic stagecoach accident at the age of 19. On November 10, 1875, the trustees accepted a proposal by the Proudfits to build an observatory in his honor, noting that the gift was "not only a valuable contribution to science and learning, but also an appropriate memorial to their lamented son".[21] The building was constructed on the precipice of the hill near where Walker Lab now stands. Some of the foundations of the building may still be intact, lying beneath what is now a small garden. The central part of this building was two stories high, and was topped with an impressive dome measuring 29 feet in diameter. The original design intended the eastern wing to be used for "meridian instruments" while the western wing would be used for "computation and a library". The dome was by far the most interesting feature of this building and was innovative in being one of the first paper domes constructed. The Hall process had not been invented, so aluminium was still more expensive than gold, and paper was a practical material. The design and construction was overseen by Prof. Dascom Greene, a professor of mathematics and astronomy, who may be considered the inventor of the paper design. Prof. Greene provided the following rationale for paper construction:[22]

I ascertained that a dome of the dimensions required, constructed in any of the methods in common use, would weigh five to ten tons, and require the aid of cumbersome machinery to move it. It therefore occurred to me to obviate this objection by making the frame-work of wood, of the greatest lightness consistent with the requisite strength, and covering it with paper of a quality similar to that used in the manufacture of paper boats; the principal advantages in the use of these materials being that they admit of great perfection of form and finish, and give extreme lightness, strength, and stiffness in the structure ...

Prof. Greene contracted E. Waters & Sons, a firm in Troy known for boat manufacture, to work on the project. In 1878 they finished the paper observatory dome for the newly erected building. The construction method was almost identical to that used at the time for paper boats: thick linen paper was formed over a mold with a wooden framework, which was removed from the mold along with the paper. Finished sections were bolted together and the joints were weatherproofed with cotton cloth saturated with white lead. The RPI dome was 29 feet in diameter and consisted of 16 sections plus a 4-foot wide shuttered opening for the telescope. The paper material was 1/6 of an inch thick and was described as "hard as wood".[23] It weighed 4000 pounds, of which paper probably accounted for 1000 pounds. The dome was supported by six eight-inch cannonballs, which moved between grooved iron tracks, allowing the dome to "be easily revolved by a moderate pressure applied directly without the aid of machinery."[22] The method of paper dome construction was utilized in several other observatories in the Northeast, including one at West Point. A patent was issued to E. Waters & Sons in 1881.

Sadly, while records show there were a few small telescopes, a large telescope was never housed in the observatory due to lack of funding, and because of this it was never of much use to the university. In 1900 the dome was replaced by a roof and a second story was added to the three wings. The building was partially destroyed by fire in 1902. As part of the renovation in 1903, a third story was added and the basement deepened. The building became a laboratory for mechanical and electrical engineering. The building went through several renovations and other uses and was eventually razed in 1959. The only physical reminder of this structure is the archway keystone which is memorialized on the southern entrance of the Science Center in 1961.[20]

First fraternities

The first fraternity at RPI was Theta Delta Chi, founded in 1853 after being started in 1847 at Union College.[24] This fraternity spread to 40 other campuses, bu no longer exists at RPI. The next fraternities were Sigma Delta in 1859 followed by the Alpha (first national) chapter of Theta Xi and Delta Phi in 1864.[25] Many others soon followed. In 1898 the first association of Latin American students in the United States was formed at RPI, called the Union Hispano-Americana.[26] This organization would later merge with other like-minded organizations and form the first Latin American fraternity in the United States, Phi Iota Alpha, in 1931.[27]

Since 1900

| Enrollment History:[15] | |

|---|---|

| 1825: 10 students | |

| 1850: 53 students | |

| 1900: 225 students | |

| 1910: 650 students[28] | |

| 1925: 1,240 students | |

| 1945: 1,604 students | |

| 1950: 3,987 students (dormitory construction on "Freshman Hill") | |

| 1965: 5,232 students | |

| 2013: 6,995 students[29] | |

RPI enjoyed a period of academic and resource expansion under the leadership of President Palmer Ricketts. Born in 1856 in Elkton, Maryland, Ricketts came to RPI in 1871 as a student.[30] Named president in 1901, Ricketts liberalized the curriculum by adding the Department of Arts, Science, and Business Administration, in addition to the graduate school. He also expanded the university's resources and developed RPI into a true polytechnic institute by increasing the number of degrees offered from two to twelve; these included electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, biology, chemistry, and physics. During Rickett's tenure, enrollment increased from approximately 200 in 1900 to a high of 1700 in 1930.[15]

After fires completely destroyed what was then RPI's Main Building in 1904, the administration and trustees decided to move the institute further east up the hill. The city of Troy responded by building the "Approach", a massive granite staircase on the former site of the Main Building as a representation of the interdependence of the industrialised city of Troy and the institute. The project cost $40,000.[31] The Approach became an important link among students travelling to and from Troy.

In 1909 alumni of city of Pittsburgh provided funds for the Pittsburgh Building, the current home of the Lally School of Management. This was the first instance in American history that alumni of a single city raised money to erect a building on a college campus.[32]

Margaret Sage's donations

Russell Sage was a titan of the railroad industry who accumulated great wealth. The woman who became his second wife, Olivia Slocum, was a Troy schoolteacher, who had attended the Troy Female Seminary (today's Emma Willard School). When they married she was 41, he was 53. The marriage was not out of love; Sage needed someone to call his wife so that he would not be the prey of "seduction lawsuits". There is no indication that Olivia and Russell ever really cared for each other, and it seems even less likely that they were ever intimate. Sage continued to have affairs with women until his later years. Russell Sage was elected onto the institute's board of trustees on June 24, 1896.[33] His only relative to attend RPI was a nephew, Russell Sage, Jr., who graduated in 1859.[33]

Many an admissions tour has told prospective students that Russell Sage hated three things: (1) philanthropy, (2) higher education, and (3) women. While such extreme accusations are false, there were circumstances that would lead to such a conclusion. He was not averse to loaning money under the assumption that it would be paid back in full, but he loathed the idea of philanthropy for its own sake. His education ended at grade school, and he was somewhat predisposed to mistrust the educated of his time. And, while there was little affection between him and his second wife, Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage, there is no other evidence suggesting that he hated women in general.[34]

Sage died in 1906, during a vacation that his doctor requested he take to get away from the business. Olivia found herself with a $70 million will, and became the wealthiest woman in the United States.[33] She immediately established the Russell Sage Foundation to aid in promoting social and educational causes. In particular, she fought for better women's education.

Olivia Slocum Sage made two large contributions to RPI. The first was funds for the building of the Russell Sage Laboratory, which was to house the new mechanical and electrical engineering departments. When Palmer Ricketts, then president, sent her a letter suggesting the building of these departments, Olivia replied with a letter which said, in effect, "Good idea." To lend some weight to her letter, she also enclosed a check for $100,000. Eventually, the total sum donated for that purpose reached one million dollars.[33] The other major contribution came in the wake of a new addition to the Quadrangle dorms. During the planning for the White dorm extensions, Olivia Slocum wrote President Ricketts stating that she would offer $100,000 for the construction of a dining hall. This hall was to be named after her nephew, Russell Sage, Jr.[33]

World War II

During World War II, Rensselaer was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program that offered students a path to a Navy commission.[35]

Post World War II expansion

| Samuel Blatchford | 1824–1828 |

| John Chester | 1828–1829 |

| Eliphalet Nott | 1829–1845 |

| Nathan S.S. Beman | 1845–1865 |

| John F. Winslow | 1865–1868 |

| Thomas C. Brinsmade | 1868 |

| James Forsyth | 1868–1886 |

| William Gurley | 1886 – 1887 (acting) |

| Albert E. Powers | 1887 – 1888 (acting) |

| John H. Peck | 1888–1901 |

| Palmer C. Ricketts | 1901–1934 |

| Edwin Seton Jarrett | 1934–1935 (acting) |

| William O. Hotchkiss | 1935–1943 |

| Livingston W. Houston | 1944–1958 |

| Richard G. Folsom | 1958–1971 |

| Richard J. Grosh | 1971–1976 |

| George M. Low | 1976–1984 |

| Daniel Berg | 1984 – 1985 (acting) 1985 – 1987 |

| Stanley I. Landgraf | 1987 – 1988 (acting) |

| Roland W. Schmitt | 1988–1993 |

| R. Byron Pipes | 1993–1998 |

| Cornelius J. Barton | 1998 – 1999 (acting) |

| Shirley Ann Jackson | Since 1999 |

As with many US universities, a period of rapid expansion occurred following the war. Enrollment for the 1946 school year was so high that temporary dormitories had to be constructed. Fifty surplus metal military barracks, each housing twenty students, were arranged into a trailer-park like camp over a mile from campus, nicknamed "tin town".[37] This arrangement was used by students until new freshman residence halls were opened in 1953. The new dorm complex, affectionately called "Freshman Hill", was subsequently expanded with the Commons Dining Hall in 1954, two more halls in 1958, and three more in 1968, just in time for the baby boomers. The year 1961 saw major progress in academics at the institute with the construction of the Gaerttner Linear Accelerator, then the most powerful in the world,[38] and the Jonsson-Rowland Science Center. In addition to new academic buildings, the growing student body also needed a larger student union, which was finished in 1967.

Donations of John Erik and Margaret Jonsson

J. Erik Jonsson, a Rensselaer alumnus of the class of 1922 and co-founder of Texas Instruments, along with his wife Margaret, did much to improve the appearance and facilities of RPI. Their first major contribution came in 1961 when they gifted the institute and led to the construction of the Science Center, on a twenty-acre site of land that the school had just purchased from the Catholic Seminary in 1958.[33]

The next major gift to Rensselaer was $2,600,000 toward the construction of a new engineering center. The initial cost estimate for the building, as given to the New York State Dormitory Fund on March 4, 1975, was $11,808,100. While the Dormitory Fund did cover some of it, a 30-year bond was taken to cover most of the cost of the building. RPI intended to cover the bond with gifts, despite the annual payments of $202,000.[33]

The actual groundbreaking was to be initiated by Margaret Jonsson; however, she was in Dallas, Texas at the time. A small charge was set up to be detonated by a phone call that Mrs. Jonsson made ... thus the term "dial-a-bomb" came to be the description of the event on April 15, 1975, at eleven o'clock. The '86 Field became the '43 Field, as construction equipment and much of the fill that was excavated for the basement of the Center (4000 cubic yards) was placed on the playing surface, cutting the field almost precisely in half down the long axis. The half of the field that was buried with fill became known as Mount Fogarty. The Jonsson Engineering Center opened in August 1977, and became a center piece of the "Rensselaer 2000 plan".[33]

The Voorhees Computing Center

A 1977 study detailed options for a new computer center to replace the Amos Eaton facility and house a 'brand-new' IBM 3033. The study was to choose among three plans. The first two proposals sought to build the center on top of or below the Armory Parking Lot. The third plan suggested renovating the Seminary Chapel, which was empty as of the opening of the Folsom Library. The Chapel option was not favored by either the architecture group doing the study, nor by the trustees, but a student referendum overwhelmingly chose the old church building as the site, remarking on the aesthetic beauty of the Chapel versus yet another "high-tech" edifice.[33] According to students who were present at the time these decisions were deliberated, the student referendum was not considered; the item which tipped the scales in the favour of the chapel as a computer center was that the estimated cost of the Armory computer center nearly doubled between the initial cost estimates and the final decision. With Alan Voorhees' $3.4 million gift (the largest single donation in RPI's history up to that time) the Voorhees Computing Center went under construction. The center opened on Oct 9, 1979.[33] To save energy costs, the heat generated by the computer within kept the building warm during the winter.[33] With the advent of newer computers generating less heat, a more traditional heating system was installed.

Continued expansion and the CII

The period 1970–1990 brought continued growth to the campus. It was during these years that the university began to become proactive in helping businesses. In 1980, several researchers and graduate students who wished to start a company approached the administration and asked for a place to set up a small lab.[39] The administration provided a basement in an old engineering building. Two weeks later, another start-up company made a similar request. It was at this point that the "H-building", which had previously been used for storage, became the home for the RPI incubator program, the first such program sponsored solely by a university.[40] Shortly thereafter, RPI invested $3 million in pavement, water and power on around 1,200 acres (490 ha) of land it owned 5 miles (8.0 km) south of campus.[39] Now known as the Rensselaer Technology Park, companies may rent the land and collaborate with RPI students and researchers. As companies began to move in, the New York State government realized how the university was helping the local economy. This is one of the reasons legislation was passed to grant RPI $30 million to build the George M. Low Center for Industrial Innovation, a center for industry-sponsored research and development.

During the 1970s "The Approach" had been closed due to disrepair. Several subsequent attempts to refurbish it failed and by the 1990s it had accumulated large amounts weeds and graffiti. In 1994 the Louis and Hortense Rubin Foundation launched the "Approach and Beyond campaign" with a $100,000 gift. The campaign raised most of the $850,000 needed.[31] After extensive renovation and landscaping, the Approach was officially reopened and renamed at a celebration on October 14, 1999.[31]

The Jackson administration

1999 saw the arrival of President Shirley Ann Jackson. A graduate of MIT, Jackson had held physics research positions at Bell Laboratories and Rutgers University, and had most recently served as chairperson for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. She instituted the "Rensselaer Plan", an ambitious plan to revitalize the institute. That same year, RPI gained attention when it was one of the first universities to implement a mandatory laptop computer program. Many saw the program as unnecessary, costly, and rushed into practice too quickly by the administration.[41] However, the program has persisted, and remains an integral part of life at RPI, with many courses requiring that a student bring their laptop to class.

In the following years Jackson's leadership began to not sit well with many faculty; on April 26, 2006, RPI faculty voted 149 to 155 in a failed vote of no-confidence in Jackson.[42] In August 2007, Jackson's administration disbanded the faculty senate and called for a full review of faculty governance, prompting a strong reaction from the Rensselaer community, including faculty petitions against the measure and a faculty hosted "teach in".[43][44]

On October 4, 2008, RPI celebrated the grand opening of the $220 million Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center. About two months later, President Jackson announced via email that there would be Institute-wide layoffs due to "the global and national economic crisis, and its impact on endowments."[45] On December 16, 2008, RPI eliminated 98 positions across the Institute, about five percent of its workforce.[46]

Bibliography

- Baker, Ray Palmer (1924). A Chapter in American Education: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824–1924 (PDF). New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 1982907.

- Greene, Benjamin Franklin (1855). The Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: Its Reorganization in 1849–50, Its Condition at the Present Time, Its Plans and Hopes for the Future (PDF). Troy, NY: D.H. Jones & Co. OCLC 41976314.

- Nason, Henry B. (1855). Biographical Record of the Officers and Graduates of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824–1886 (PDF). Troy, NY: D.H. Jones & Co. OCLC 1675616.

- Phelan, Thomas; D. Michael Ross; Car Westerdahll (1995). Rensselaer: Where Imagination Achieves the Impossible. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. OCLC 33427362.

- Rezneck, Samuel (1968). "Education for a Technological Society: A Sesquicentennial History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute" (PDF). Troy, NY: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. OCLC 33427362. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ricketts, Palmer C. (1934). History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824–1934, Third Edition (PDF). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. OCLC 3050727.

References

- "RPI History". Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Retrieved May 1, 2009. Note: a possible competitor for this title is the United States Military Academy (USMA) at West Point, which claims to have the oldest engineering department in the US Archived August 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. While this is true, it is still true that RPI offered the first engineering degree (Civil Engineering) in 1835. The statement of being 'the oldest" is thus justified in different ways by both. The modifier "in continuous existence" appears in Ricketts, Palmer C. History of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. 2nd e.

- Griggs, Francis (January 1997). "Amos Eaton was Right!". Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice. 123 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(1997)123:1(30).

- "Rensselaer History Timeline Scroll". Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- "Rensselaer To Celebrate 50 Years of Environmental Engineering at Colloquium". RPI Press Release. March 18, 2005. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- Rensselaer Alumni Magazine (2005). "Game Design by Degree". Retrieved January 26, 2007. (More information is available at http://www.gsas.rpi.edu/ )

- D'Errico, Richard A. (September 2, 2005). "Early in the game: RPI creates video game major". The Business Review. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- "RPI Archives of First Women at Institute". RPI.edu. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- Weise, Arthur James (1886). The City of Troy and its Vicinity. Troy, NY: Edward Green.

- McAllister, E. M. (1941). Amos Eaton: Scientist and Educator 1776–1842. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Helfrich, K. (2006). Amos Eaton., quote from the founding letter written by Stephen van Rensselaer

- Ricketts, Palmer C. (1934). "History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824–1934, Third Edition". New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 34. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Institute Archives and Special Collections. "RPI Building Histories". Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- Wicks, Frank (July 1999). "The blacksmith's motor". Mechanical Engineering Magazine. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- "Timeline of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute History 1999". Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- "NEB&W Guide to the History of RPI". Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- Nehrich, John (January 27, 2010). "Classic buildings result of citywide fire". Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- Weise, Arthur James (1891). Troy's One Hundred Years 1789–1889. Troy, NY: William H. Young.

- "Troy Irish Genealogy Society".

- "The Infant School Property". RPI Building Histories. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- "Williams Proudfit Astronomical Observatory". RPI Archives Building Histories. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- Nason. pg 6

- Cupery, Ken. "Paper Observatory Domes". Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- American Architect & Building News. Jan 25, 1879, p 30.

- Lutzky, Raymond A. "History of Greek Life at RPI". RPI Alumni Association. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- "Founding of Theta Xi". Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- Ricketts, Palmer C. (1934). A History of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1824–1934. New York, New York: Wiley Publishing Company.

- Anson, Jack L.; Robert F. Marchesani Jr (1991). Baird's Manual of American College Fraternities. Menasha, Wisconsin: Banta Publishing Company. VIII-22. ISBN 978-0-9637159-0-6.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 319.

- "Quick Facts". Retrieved February 23, 2014.

- "RPI Biography of Palmer Ricketts". Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- "The Approach". RPI Archives. Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- "History of the Pittsburgh Building". Archived from the original on October 30, 2006. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- "Not the Rensselaer Handbook". Retrieved June 20, 2011. original text by Steve Staton, Tom White, and others September 18, 1985. Text was subsequently published on the "Not the Rensselaer Wiki" and released into public domain under GNU. See here for more info

- Sarnoff, P. (1965). Russell Sage: The Money King. New York City: Ivan Obolensky.

- "Shots from RPI". Troy, New York: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- "Rensselaer Archives and Special Collections: RPI Presidents". Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ""Tin Town" on Rensselaer Building Histories site".

- "History of RPI's Gaerttner Linear Accelerator". Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- Le Maistre, C.W. (1989). "Academia linking with industry-the RPI model". Academia Linking With Industry: the RPI model. pp. 207–208. doi:10.1109/EMTS.1989.68976.

- "RPI's Incubator Program History". February 2010. Archived from the original on August 19, 2010. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- Monahan, Torin (2003). "Hot Technologies on Every Pillow". Radical Pedagogy. 4 (1).

- "No-Confidence Motion Fails at Rensselaer Polytechnic". The Chronicle of Higher Education. April 27, 2006.

- RPI (2007). "Faculty Governance Review". Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- Times Union (2007). "RPI professors stage '60s-style teach-in". Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- "Layoffs Coming to RPI". Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- "For RPI, priorities an issue: Layoffs spark questions about school's spending on construction, salaries". Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2008.