History of Rakhine

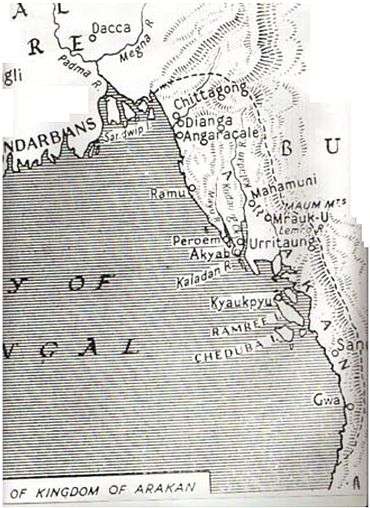

Rakhine State occupies the northern coastline of Myanmar up to the border with Bangladesh and corresponds to the historical Kingdom of Arakan. The history of Rakhine is divided into 7 parts - the independent kingdoms of Dhanyawadi, Waithali, Lemro, Mrauk U, Burmese occupation from 1784 to 1826, British rule from 1826 to 1948 and as a part of independent Burma from 1948.

| History of Myanmar |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

The Arakanese kingdom was conquered on 31 December 1784 by the Burmese Konbaung Dynasty. In 1826, Arakan was ceded to the British as war reparation after the First Anglo-Burmese War. It became part of the Province of Burma of British India in 1886, after the annexation of Burma by the British. Arakan became part of the Crown Colony of British Burma which was split off from British India in 1937. Northern Rakhine state became a contested battleground throughout the Japanese occupation of Burma. After 1948, Rakhine became part of the newly independent state of Burma. However, the independence of Arakan was just in paper after a few years because Myanmenization or nationalism of Myanmar broke up civil war across nationwide. In 1973, Arakan became a state of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma, designated as the homeland of the Rakhine people.

Sporadic communal strife has plagued Arakan since colonial times, between the majority Arakanese who are Buddhist, and Muslim communities, many but not all of whom came into Arakan with British rule. The latest conflagration was in June and October 2012.

Dhanyawadi

Arakanese legends claim that the history of the Rakhine people began in 3325 BC, although archaeological evidence supporting this claim is unavailable. "The presently dominant Rakhine are a Tibeto-Burman race, the last group of people to enter Arakan during 10th century and on.” (Pamela; The Lost Kingdom, Bangkok, 2002, P-5)]. Various Arakanese kingdoms stretched from the Ganges Delta to Cape Negrais on the Irrawaddy Delta.

Ancient Dhanyawadi lies west of the mountain ridge between the Kaladan and Le-mro rivers. Dhannyawadi could be reached by small boat from the Kaladan via its tributary, the Tharechaung. Its city walls were made of brick, and form an irregular circle with a perimeter of about 9.6 kilometres (6.0 miles), enclosing an area of about 4.42 km2 (1,090 acres). Beyond the walls, the remains of a wide moat, now silted over and covered by paddy fields, are still visible in places. The remains of brick fortifications can be seen along the hilly ridge which provided protection from the west. Within the city, a similar wall and moat enclose the palace site, which has an area of 26 hectares (64 acres), and another wall surrounds the palace itself.

At times of insecurity, when the city was subject to raids from the hill tribes or attempted invasions from neighbouring powers, there would have been an assured food supply enabling the population to withstand a siege. The city would have controlled the valley and the lower ridges, supporting a mixed wet-rice and taungya (slash and burn) economy, with local chiefs paying allegiance to the king.

From aerial photographs we can discern Dhannyawadi's irrigation channels and storage tanks, centred at the palace site. Throughout the history of Rakhine, and indeed the rest of early Southeast Asia, the king's power stemmed from his control of irrigation and water storage systems to conserve the monsoon rains and therefore to maintain the fertility and prosperity of the land. In ceremonies conducted by Indian Brahmins the king was given the magic power to regulate the celestial and terrestrial forces to control the coming of the rains which would ensure the continuing prosperity of the kingdom.

Vesali (Waithali)

It has been estimated that the centre of power of the Arakanese world shifted from Dhanyawadi to Waithali in the 4th century AD. Although it was established later than Dhanyawadi, Waithali is the most Indianized of the four Arakanese kingdoms to emerge. Like other Arakanese kingdoms, the Kingdom of Waithali was based on trade between the East (pre-Pagan Myanmar, Pyu, China, the Mons), and the West (India, Bengal, Persia).

The Anandachandra Inscriptions that date back to 729 AD, originally from Vesali (now preserved at Shitethaung), indicates adequate evidence for the earliest foundation of Buddhism and the subjects of the Waithali Kingdom practised. Dr. E. H. Johnston's analysis reveals a list of kings which he considered reliable beginning from Chandra dynasty. The western face inscription has 72 lines of text recorded in 51 verses describing the Anandachandra's ancestral rulers. Each face recorded the name and ruling period of each king who were believed to have ruled over the land before Anandachandra.

Important but badly damaged life-size Buddha images were recovered from Letkhat-Taung, a hill east of the old palace compound. These statues are invaluable in helping to understand the Waithali architecture, and also the extent of Hindu influence in the kingdom.

According to local legend, Shwe-taung-gyi (lit. Great Golden Hill), a hill northeast of the palace compound maybe a burial place of a 10th-century Pyu king.

The rulers of the Waithali Kingdom were of the Chandra dynasty, because of their usage of Chandra on the Waithali coins. The Waithali period is seen by many as the beginning of Arakanese coinage - which was almost a millennium earlier than the Burmese. On the reverse of the coins, the Srivatsa (Arakanese/Burmese: Thiriwutsa), while the obverse bears a bull, the emblem of the Chandra dynasty, under which the name of the King is inscribed in Sanskrit.

Le-Mro

Le-Mro or Lay Mro in the Rakhine language means "four cities," which refers to the four ancient Rakhine cities that flourished by the side of the Lemyo River.

Mrauk U

_no_primeiro_plano_o_bairro_portugu%C3%AAs.jpg)

Mrauk U may seem to be a sleepy village today but not so long ago it was the capital of the Arakan empire where Portuguese, Dutch and French traders rubbed shoulders with the literati of Bengal and Mughal princes on the run. Mrauk U was declared capital of the Arakanese kingdom in 1431. At its peak, Mrauk U controlled half of Bangladesh, modern day Rakhine State (Arakan) and the western part of Lower Burma. Pagodas and temples were built as the city grew, and those that remain are the main attraction of Mrauk-U. From the 15th to 18th centuries, Mrauk U was the capital of a mighty Arakan kingdom, frequently visited by foreign traders (including Portuguese and Dutch), and this is reflected in the grandeur and scope of the structures dotted around its vicinity.[1]

The old capital of Rakhine (Arakan) was first constructed by King Min Saw Mon in the 15th century, and remained its capital for 355 years. The golden city of Mrauk U became known in Europe as a city of oriental splendor after Friar Sebastian Manrique visited the area in the early 17th century. Father Manrique's vivid account of the coronation of King Thiri Thudhamma in 1635 and about the Rakhine Court and intrigues of the Portuguese adventurers fire the imagination of later authors. The English author Maurice Collis who made Mrauk U and Rakhine famous after his book, The Land of the Great Image based on Friar Manrique' travels in Arakan.

The Mahamuni Buddha Image, which is now in Mandalay, was cast and venerated 15 miles from Mrauk U where another Mahamuni Buddha Image flanked by two other Buddha images. Mrauk U can be easily reached via Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine State. From Yangon there are daily flights to Sittwe and there are small private boats as well as larger public boats plying through the Kaladan river to Mrauk U. It is only 45 miles from Sittwe and the seacoast. To the east of the old city is the famous Kispanadi stream and far away the Lemro river. The city area used to have a network of canals. Mrauk U maintains a small archaeological Museum near Palace site, which is right in the centre of town. As a prominent capital Mrauk U was carefully built in a strategic location by levelling three small hills. The pagodas are strategically located on hilltops and serve as fortresses; indeed they are once used as such in times of enemy intrusion. There are moats, artificial lakes and canals and the whole area could be flooded to deter or repulse attackers. There are innumerable pagodas and Buddha images around the old city and the surrounding hills. While some are still being used as places of worship today, others are in ruins, some of which are now being restored to their original splendor.[2]

The city eventually reached a size of 160,000 in the early 17th century.[3] Mrauk U served as the capital of the Mrauk U kingdom and its 49 kings until the conquest of the kingdom by the Burmese Konbaung Dynasty in 1784.

Trading city

Due to its proximity to the Bay of Bengal, Mrauk U developed into an important regional trade hub, acting as both a back door to the Burmese hinterland and also as an important port along the eastern shore of the Bay of Bengal. It became a transit point for goods such as rice, ivory, elephants, tree sap and deer hide from Ava in Burma, and of cotton, slaves, horses, cowrie, spices and textiles from Bengal, India, Persia and Arabia. Alongside Pegu and later Syriam, it was one of the most important ports in Burma until the 18th century.

The city also traded with non-Asian powers such as Portugal and then the VOC of the Netherlands. The VOC established trading relations with the Arakanese in 1608 after the Portuguese fell in favour due to the lack of loyalty of Portuguese mercenaries, such as Filipe de Brito e Nicote in the service of the Arakanese king. The VOC established a permanent factory in Mrauk U in 1635, and operated in Arakan until 1665.[4]

At its zenith, Mrauk U was the centre of a kingdom which stretched from the shores of the Ganges river to the western reaches of the Ayeyarwaddy River. According to popular Arakanese legend, there were 12 'cities of the Ganges' which constitute areas around the borders of present-day Bangladesh which were governed by Mrauk U, including areas in the Chittagong Division. During that period, its kings minted coins inscribed in Arakanese, Arabic and Bengali.

Much of Mrauk U's historical description is drawn from the writings of Friar Sebastian Manrique, a Portuguese Augustinian monk who resided in Mrauk U from 1630 to 1635.

Colonial period

The people of Rakhine (Arakan) resisted the conquest of the kingdom for decades after. Fighting in border areas created problems between British India and Burma. The year 1826 saw the defeat of the Bamar in the First Anglo-Burmese War and Rakhine (Arakan) was ceded to Britain under the Treaty of Yandabo. Akyab was then designated the new capital of Rakhine (Arakan). In 1852, Rakhine (Arakan) was merged into Lower Burma as Arakan Division.

During the Second World War, Rakhine (Arakan) was given autonomy under the Japanese occupation and was even granted its own army known as the Arakan Defence Force. The Arakan Defence Force went over to the Allies and turned against the Japanese in early 1945.

Part of independent Burma

Upon independence in 1948, Rakhine (Arakan) became a division within the Union of Burma. Shortly after, violence broke out along religious lines between Buddhists and Muslims. Later there were calls for secession by the Rakhine (Arakan), but such attempts were subdued. In 1974, the Ne Win government's new constitution granted Rakhine (Arakan) Division the status of a Union state. In 1989, the name of Arakan State was changed to "Rakhine" by the military junta.

Communal strife

See also

- List of Arakanese monarchs

- Pyu city states

- Rakhine people

- Rakhine State

References

- Richard, Arthus (2002). History of Rakhine. Boston, MD: Lexington Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-7391-0356-3. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- William, Cornwell (2004). June 2013 History of Mrauk U Check

|url=value (help). Amherst, MD: Lexington Books. p. 232. ISBN 0-7391-0356-3. - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/1887/12637/11/08.pdf

Bibliography

- Charney, Michael W. (1993). 'Arakan, Min Yazagyi, and the Portuguese: The Relationship Between the Growth of Arakanese Imperial Power and Portuguese Mercenaries on the Fringe of Mainland Southeast Asia 1517-1617.' Masters dissertation, Ohio University.

- Leider, Jacques P. (2004). 'Le Royaume d'Arakan, Birmanie. Son histoire politique entre le début du XVe et la fin du XVIIe siècle,' Paris, EFEO.

- The Land of the Great Image: Being Experiences of Friar Manrique in Arakan, Maurice Collis (1943), (US publication 1958, Alfred A. Knopf)

- Aye Chan.The Kingdom of Arakan in the Indian Ocean Commerce (AD 1430 - 1666)(2012),The Bulletin of the Bu San University of Foreign Studies, Korea.