History of Grant County, Kansas

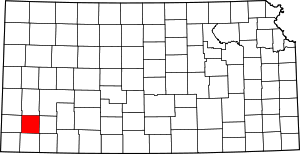

Grant County is a county located in southwest Kansas, in the Central United States. Its county seat and only city is Ulysses.[1]

Introduction

Grant county is located in the High Plains region in the southwestern corner of Kansas, with its western edge being 27 miles from the Colorado state line, and its southern edge 26 miles from the Oklahoma border, as these perimeters are currently delineated. It lies between the 37th and 38th parallels, and the 101st and 102nd meridians. The elevation at Ulysses Kansas, county seat in the center of the county, is 3,050 feet above sea level.[2]

The county is 24 miles square, and, generally speaking, is flat land, with the exception of the bluffs and breaks on the Cimarron River, which flows along the south edge of the county, the rolling country bordering the North Fork of the Cimarron River in the center of the county, and along Bear Creek in the northwestern corner. The streams flow eastward and carry little water under normal conditions, although rains falling to the west of the area tend to create flood conditions, as the streams have a fall of as much as eight feet to the mile in some places.[2] The overall width of the Cimarron River basin valley eroded in southern Grant County indicate in historical times past, it has been a raging river of significant proportions.

The focal points of prehistory and early history of what became Grant county are the ancient spring on the Cimarron now known as Wagonbed Springs, and the trading path trod by countless natives beside it which eventually came to be called the Santa Fe Trail.[2]

Prehistoric Era

Mastodon tusks and bones dated at about five million years ago, petrified trees and ferns deep in the river banks, even imprints of water creatures in limestone, bear witness that western Kansas was not always an arid plain.[2]

Vast deposits of natural gas means that millions of years ago this was a semi-tropical region with much vegetation. Even prior to that, it was an inland ocean.[2]

Workers on the railroad in 1922 thought they had found a victim of an Indian raid on the Santa Fe Trail when they uncovered a skeleton of a young woman while making the railroad cut east of Ulysses Kansas. They couldn't understand why she had been buried standing up, but they carefully collected her bones and re-buried her in the Ulysses Kansas cemetery. It can only be conjecture now that this might have been a prehistoric upright burial similar to others found in the region.[2]

Pottery found in the southeast corner of the county was dated by the Smithsonian Institution at 200-800 A.D., and some found nearby is believed to be older than that.[2]

Native Indian Era

For thousands of years, this has been Nature's pastureland. Millions of shaggy buffalo roamed and bellowed over the prairies, and with them moved the medicine and tools to the nomadic tribes that followed the herds; everything they needed, walking supermarkets. The smallest bone became a needle and the thinnest sinew, thread. Those natives left evidence in passing: weapon points of flint, circles burnt into the soil, grinding stones and scraping knives, axes and hoes.[2]

Spanish Era

Some 60 years before the English ventured onto the eastern shores of the North American continent, the history of what was to become far western Kansas was being written in the Spanish language.[2]

Some segment of the Plains Apache tribe was occupying this space when the first white man came. That man was the Spanish explorer, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, returning to Mexico disillusioned and disheartened by the grass huts of Quividra in 1541.[2]

The journal of his expedition states that they returned to New Spain (Mexico) "along a shorter route known to the natives". It is probable that the expedition was led from the Arkansas River south through the old Bear Creek pass in the sandhills to what later was the Cimarron cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail, and it is likely that they watered at the Springs on the Cimarron.[2]

This area shares history with New Mexico, because it was the Spanish who first touched and disrupted the native population of the plains. The first permanent colony in New Mexico was founded in 1598 at San Juan by Juan de Onate. A few years later, in 1610, Governor Pedro de Peralta established the capitol at Santa Fe. In the 300 years between Coronado and Santa Fe Trail days, there were 10 recorded expeditions east from New Mexico into this region, and nearly every written account mentions another, unauthorized forays onto the plains.[2]

Some of the Spaniards came, like Coronado, in search of gold and treasure. Some came under orders to search out the French traders who were encroaching upon territory claimed by Spain. And Captain Juan Ulibarri's expedition in 1706 was sent to reclaim and return Christianized Picuris pueblo Indians who had run away from Spanish domination to what is known as El Cuartelejo in Scott county, Kansas. He was disturbed by a report given him of the French who were living in walled houses on the Chinali, but because of the lateness of the season, he did not seek them further, so we remain in ignorance about which stream was the Chinali. A copy of Ulibarri's journal is in the possession of this writer, and it makes fascinating reading about how he saw eastern Colorado and western Kansas in 1706.[2]

The return of the runaway Picuris to the fold was essential. The Spanish were well aware that if one group got away with that trick, the whole native population of New Mexico might well move out from under them. Since the Spaniard had found no gold and small glory, he at least had to hang onto what he had done in the "name of God". So the rebels were escorted back to New Mexico "for the good of their eternal souls". Incidentally, it was in Captain Ulibarri's journal that he described "this plains region" as "the place where even the Apaches lose themselves".[2]

Another reason for coming east from Pecos was to capture the natives and return with them as slaves, also in the name of saving their souls. Although this was frowned upon by the government, it became a too common practice.[2]

Members of these expeditions, as man has always done, left behind evidence of their passing. The Spanish exhibit at the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka, Kansas until recently featured only three items of Spanish origin, all from southwest Kansas:

- the Gallego sword from Finney county

- the ring bit found near Plains, Kansas

- and another Toledo-made sword found in Grant county, Kansas[2]

The sword was found in 1938 by Ray Kepley in the southwest part of the county, on a hill above the North Fork (of the Cimarron River). Two similar swords have been reported as found along the North Fork, but they cannot be traced now.[2]

A French religious medallion dating about 1750 was found long ago near Wagonbed Springs, and the finder was persuaded to place it in the state Society's museum. On a research trip to Topeka, the request was made to see it and photograph it, but it couldn't be found. Accession records show that it arrived, but it is gone now; the only trace locally of the French intrusion, against which the Spanish guarded so jealously.[2]

During this "empty" period, the plains Indian tribes acquired horses, entirely changing the native cultures. The Comanche and Kiowa, the Cheyenne and the Arapaho and the fierce Pawnee became forces to be reckoned with, as they pushed southward the less mobile Plains Apaches.[2]

And more than 20 years before Atchison, Topeka and Lawrence were founded, a busy trail ran through Grant county, carrying eastern goods to Santa Fe and returning with silver and gold.[2]

The Five Flags of Grant County

The Spanish extended their borders beyond their capacity to defend, and that, combined with war and internal troubles in Spain, led eventually to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, encompassing all of Kansas except the extreme southwest corner. The Arkansas river was the northern boundary of Spanish territory, and the 100th meridian (where Dodge City, Kansas now is located) was the eastern boundary in this part of the plains. So the territory in which Grant County is located remained a foreign nation after the rest of the state belonged to the United States.[2]

Had this southwest corner of Kansas been settled between 1541 and 1854, it would have had a bewildered citizenry. During that time, while only five different nations claimed the area, ownership changed among them at least nine times. In addition, the region was under five separate territorial governments of the United States before becoming a state in 1861.[2]

The first flag over Grant and her sister counties (figuratively speaking) was that of Spain, with Coronado's expedition. The second claim was made by the French explorer, LaSalle, in 1684. Following the French and Indian War, the region was again claimed by Spain.[2]

Mexico's independence from Spain was recognized in 1821. All the territory of New Spain then became the Republic of Mexico, adding the third flag to the collection.[2]

Settlers from the east poured into Texas through the years, and in 1836, after the defeat at the Alamo and the victory at San Jacinto, Texas became an independent republic, flying the Lone Star flag. The northern and eastern boundaries remained the same.[2]

After a long argument over the slavery question, and some political maneuvering by Sam Houston with the British, this region was annexed to the Union as a rather unwanted part of the state of Texas in 1845.[2]

The area became more treasured when the federal government in 1850 agreed to pay Texas ten million dollars for its claims outside its present state borders.[2]

The Territory of Kansas was organized in 1854, including this area, along with all of Colorado to the Rocky Mountains, and reaching north along the Platte River in what is now Nebraska. The city of Denver, Colorado was founded in what was then Arapahoe county, Kansas, and was named for the territorial governor.[2]

Incredible as it now seems, when state boundaries were fixed in 1861, a total of 44,509 square miles of land, including the gold fields in the Rockies, was rejected as unfit to be part of the state of Kansas. Only because of "the possible development of this region as grazing areas" for eastern Kansas farmers was the western boundary placed as far west as it is.[2]

Establishment of County Boundaries

In 1873, the part of Kansas west of Range 25 was divided into 25 new counties. The new counties were Decatur, Rawlins, Cheyenne, Sheridan, Thomas, Sherman, Lane, Buffalo, Foote, Meade, Scott, Sequoyah, Arapahoe, Seward, Wichita, Kearny, Greeley, Hamilton, Stanton, Kansas, Stevens, and Grant.[3]

Grant County, Kansas was named after Ulysses S Grant, the 18th President of the United States (1869–1877), four star Union General in the USA Civil War, and fought in the Mexican–American War of 1846-1848.[2] The initial survey establishing county boundaries was in the summer of 1874.[2]

In 1883, Kearny, Sequoyah, Arapahoe, Kansas, Stevens, Meade, Clark and Grant counties disappeared. Hamilton, Ford, Seward, and Hodgeman counties enlarged and Finney County was created. Grant County was split with the western portion becoming a part of Hamilton County and the eastern portion becoming a part of the newly created Finney County.[3]

On June 9, 1888, Grant County was again established as a Kansas county, with original county boundaries, with the first officers of the new Grant County being sworn in on June 18, 1888.[3]

In October 1888, the county seat election for Grant County resulted in victory for Ulysses, Kansas, election results were:[3]

- Ulysses = 578

- Appomattox = 268

- Shockeyville = 41

- Golden = 31

- Spurgeon = 2

Early Day Settlements in Grant County

All the town sites have been vacated by an act of the state legislature, with the exception of New Ulysses, now called Ulysses, and Hickok.

Old / New Ulysses

- "Old" Ulysses was located on S36-T-28-R37, established 1885. It became a thriving typically western town of about 1500 inhabitants. It boasted four hotels, twelve restaurants, twelve saloons, a bank, six gambling houses, a large school house, a church, a newspaper office and an opera house. "Old" Ulysses, subsequently moved to New Ulysses in 1909.[2]

- "New" Ulysses - The original townsite of "New" Ulysses, established June 30, 1909 (plat map filing date), is located on S27-T28-R37, as the southwest quarter of said section.[2] Currently, due to municipal expansion from additions and subdivisions, city limit perimeters encompass a much larger area.

Surprise-Tilden

Located on S16-T28-R37, Surprise was established in 1885. John Arthur, E. R. Watkins, Frederick Ausmus, Henry H. Cochran, and George W. Cook were some of the early day settlers. The name of the post office was changed to Tilden in 1887.[2]

Cincinnati-Appomattox

Located on S28-T28-R37, Cincinnati was established in 1887. The name was later changed to Appomattox. It had a population of about 1,000 and was the chief contender for the county seat.[2]

Shockey (Shockeyville)

Located on S29-T27-R38, Shockey was established in 1886 and grew to a town of fifty inhabitants.[2]

Golden

Located on S34-T29-R38, Golden was established in 1886 with a population of 50. The Golden cemetery is in the vicinity of the old village.[2]

Zionville

Located on S16-T30-R37, Zionville was established in 1885. M. M. Wilson was one of the early settlers and erected a store building which became the center of activity of the town. Sunday School and church services were held in the Wilson home. This town was about 10 miles south of New Ulysses, with the Zionville cemetery slightly southwest.[2]

Lawson

Located on S27-T29-R35, Lawson was established in 1886. The population of the town was 25.[2]

Waterford

Located on S33-T30-R35, Waterford was established in 1886. It was an Irish settlement on the border of the Grant and Stevens county lines near the Cimarron River.[2]

Gognac

Located on S36-T28-R39, Gognac (or Goguac) was established in 1885 in Stanton County, Kansas; however, later the post office was moved to Grant County, Kansas. The town consisted of one building and a store and post office combined.[2]

Spurgeon

Located on S28-T27-R35, Spurgeon had a population of 15. The town lasted but four years.[2]

Rock Island

Located on S26-T28-R37, a town plat was filed, but never developed, although many lots were sold, some to people who never saw the land. There were no buildings erected or improvements of any kind put on the land. There was no post office.[2]

Hickock

Located on S2-T29-R36, a town plat was filed on May 15, 1928, and a small unincorporated community currently exists here.[2]

References

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Bessire, Fern (1982). Grant County, Kansas. Grant County History Commission.

- Ulysses 1885-1909 From Boom to Bust; compiled by The Historic Adobe Museum Staff of Ulysses, Kansas; 2009.

Further reading

- History of the State of Kansas; William G. Cutler; A.T. Andreas Publisher; 1883. (Online HTML eBook)

- Kansas : A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc; 3 Volumes; Frank W. Blackmar; Standard Publishing Co; 944 / 955 / 824 pages; 1912. (Volume1 - Download 54MB PDF eBook),(Volume2 - Download 53MB PDF eBook), (Volume3 - Download 33MB PDF eBook)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grant County, Kansas. |

- Official sites

- Maps

- Grant County Map, GrantCoKs.org

- Grant County Map, KDOT