History of Chincoteague, Virginia

The history of human activity in Chincoteague, on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, begins with the Native Americans. Until European settlers possessed the island in the late 17th century, the Chincoteague Indians used it as a place to gather shellfish, but are not known to have lived there; Chincoteague Island lacked suitable soil for their agriculture. The island's name derives from those early visitors: by one popular tale, chincoteague meant "Beautiful land across the water" in their language.

Use of Chincoteague Island by European settlers began in the 17th century, when the island was granted to a Virginia colonist. Legal disputes followed, and it was not until 1691 that title was determined by the courts. Although a few people were living on the island by 1700, it was primarily used as a place to graze livestock. This was probably the origin of the Chincoteague ponies, feral horses that long roamed in the area. They are no longer present in the wild on Chincoteague Island. During the American Revolutionary War, the islanders supported the new nation's bid for independence. The local fishing and seafood resources began to be systematically exploited in the early 19th century.

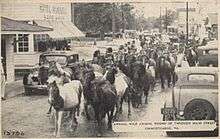

In the Civil War, the islanders supported the Union despite being located in a seceded state, and the war touched Chincoteague only lightly. Oysters became a major industry in the postwar years. Chincoteague's relative isolation ended in 1876 with the arrival of the railroad at Franklin City, Virginia, across Chincoteague Bay from the island, and the initiation of a dedicated steamboat service between the two settlements. Nevertheless, contemporary visitors found Chincoteague primitive. Part of the island was incorporated as the Town of Chincoteague within Accomack County in 1908; the municipality annexed the remainder of the island in 1989. Automobile traffic could reach the island with the completion of a causeway in 1922. Two devastating fires in that decade caused the establishment of the Chincoteague Fire Department in 1925; the new volunteer company took over the traditional pony penning, and soon had ponies from nearby Assateague Island swim the narrow channel between the two islands as part of that roundup. The carnival, pony swim, and subsequent auction constitute a highlight of the town's calendar, attracting tens of thousands to the island.

The seafood and poultry industries thrived through much of the 20th century, but neither is important to the island's economy today. Chincoteague is a major tourist destination on Virginia's Eastern Shore, with many coming to enjoy the beaches on Assateague Island. The success of Marguerite Henry's 1947 children's book Misty of Chincoteague and its sequels helped publicize Chincoteague, as did the 1961 film, Misty.

Setting and pre-European use

Chincoteague is the name of a town, and the barrier island on which it is located, on Virginia's Eastern Shore, in the United States.[1] The island is about 8 miles (13 km) long and 2 miles (3.2 km) wide. Sand forms its soil, with a thin layer of loam above it away from the water, enough to support pine trees and grass.[2] Chincoteague Inlet, a break in the barrier island system, occurs near Chincoteague Island, at the southern end of Assateague Island. Assateague shelters Chincoteague from the Atlantic and stretches north almost 30 miles (48 km) to Ocean City, Maryland.[1]

The local Native Americans, called by Europeans the Chincoteague Indians, did not in fact reside on Chincoteague Island itself, but lived on the mainland, where there was suitable land for hunting and agriculture. They lived near what was at first called Chincoteague Creek, on the mainland, and is today Little Mosquito Creek. The tribe moved to a new village site every few years, and visited Chincoteague Island to obtain shellfish. Although many references state that the name "Chincoteague" is the Native American word for "Beautiful land across the water", according to local historian Kirk Mariner, this legend is of 20th-century origin, invented to promote a song by that name by an islander. The name, he states, instead derives from the tribe's word for "large stream" or "inlet".[3]

The Chincoteague Indians gradually withdrew northwards in the late 17th century as European colonization grew; most settled on a reservation at present-day Snow Hill, Maryland, with allied tribes of Native Americans, though some may have remained in their traditional area. They were later forced from the reservation, and their descendants are among the Nanticoke people in southern Delaware.[4]

Colonial Chincoteague

Although Virginia was settled in 1607 with the advent of the Jamestown Colony, it was not until 1680 that Europeans occupied Chincoteague Island. A patent to Chincoteague Island had been granted by the British colonial authorities to Daniel Jenifer in 1671; that interest had been transferred to Thomas Welburn, husband of Jenifer's stepdaughter and prominent local merchant who lived on the mainland side of Chincoteague Bay. To fulfill the terms of the patent and gain title, the holder or his designee had to live on the land for a year—in the contemporary term, to "seat" the land. Welburn and several employees built a house there and cleared land for a small farm. His employee and tenant, Robert Scott, lived there only for the required year. Once it had expired, the house was abandoned, but Welburn, despite considering the land his own, did not register his efforts to perfect title.[5][6]

Unaware that Welburn had seated the land, the authorities declared Chincoteague Island abandoned and issued another patent for the land in December 1684 to John Clayton, who conveyed it to Colonel William Kendall of Northampton. When Welburn learned that Kendall was planning to seat the land himself, he threatened to shoot trespassers on the island. Instead, Welburn sued, and the case dragged on in the Accomack County[lower-alpha 1] courts until the local justices transferred it to the General Court in the capital of Williamsburg. Welburn lost the case, as the General Court ruled in 1691 that as Jenifer had never lived on the island, he had not conveyed a valid patent to Welburn. Fresh patents were then issued, dividing the island between Kendall and another prominent citizen of Northampton, Major John Robins, with the dividing line near present-day Church Street.[5][6]

Once ownership of the island was settled, it was used mostly as a place to house livestock, since there was no need for fences or other enclosures to prevent the animals from straying, and they could feed off of the marsh grasses.[7] This usage was most likely the origin of the ponies that have made Chincoteague and Assateague Islands famous, though there are legends that the ponies' ancestors survived a shipwreck of a Spanish vessel. One such ship did run aground on Assateague Island in 1750, but according to John Amrhein Jr. in his account of his efforts to locate that vessel, "the mystery of the origin of the wild ponies became fused with the oldest memories of the Spanish shipwreck".[8]

An early inhabitant was Henry Towles, who had seated the island for Kendall in 1686. He bought land from Kendall on the island, lived there, and sold it in 1709. The first permanent residents were likely George and Hannah Blake, originally tenants; their son John bought land from Kendall in the 1690s. Blake's Point, which extends out into Chincoteague Bay, testifies to their residence on the western side of the island. The will of John Robins, recorded in 1709, documents the presence of horses on Chincoteague—he bequeaths one, and mentions that his livestock were on the island. He also willed a "mallato [mulatto boy Charles son of Hannah, which said boy is now on my part of Jengoteague [sic] Island".[9] Through the 18th century the population slowly expanded until by the end of it about 200 people, mostly tenant farmers and squatters, lived on Chincoteague and Assateague.[10]

Antebellum period (1776–1860)

When the Thirteen Colonies broke away from the British Crown in 1776, early decrees of the provisional Virginia Convention affected Chincoteague. In May 1776, the body ordered that the coastal islands be stripped of livestock that might be taken by British ships. The islanders, in June, petitioned for a repeal or exemption, as they had, the petition stated, "the most fervent desire to do everything in their power to defeat the ... enemies of American liberty", as well as a militia of some forty men able to repel British raiders. The convention allowed Chincoteague and other islands along the Atlantic coast to retain their livestock.[11]

In mid-1776, the convention voted to fortify Chincoteague's harbor—it was then being used by ships evading the British blockade of Chesapeake Bay. Smuggled goods were unloaded on the mainland, and taken down the Eastern Shore toward more populated areas. The resulting fort was built on Wallops Island, across the inlet from Chincoteague. The smuggling route maintained its importance as the American Revolutionary War continued, and in August 1779, the sole action in the area took place—a British privateer, pretending to be a smuggler, disabled the fort's guns and captured a cargo ship at anchor in Chincoteague Bay. Island legend holds that four men from Chincoteague fought for the Americans at the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781, and that one was delayed in returning to the island because General George Washington had the soldier transport the battle flag to the general's home at Mount Vernon.[12]

By 1800, the original large parcels of land on Chincoteague Island were being broken into plots of 30 acres (12 ha) or larger. There were some 200 people living on Chincoteague or Assateague, but there were no stores or other retail enterprises. A school, unusual for Virginia's Eastern Shore at the time, was erected sometime before 1804. Three island families were free African-Americans; two other households had black servants or slaves. One of the free African-Americans, Ocraw Brinney, became a major island landowner. Born in Africa and transported by slave ship, he was freed in 1787 and was supposedly 130 years old when he died around 1840, but was more likely aged about 100. His holdings included what today are the Carnival Grounds, south of downtown Chincoteague.[13]

In the first half of the 19th century, Chincoteague became a source of seafood. As the cities along the eastern seaboard, such as New York and Philadelphia, continued to expand, their local areas could not supply them with enough shellfish. Islanders saw the opportunity, and many abandoned agriculture, instead harvesting the sea.[14] The villagers of Chincoteague petitioned the Virginia General Assembly three times between 1833 and 1851 seeking the repeal of various fishing laws. The first post office was established in 1854, and the first doctor arrived four years later. By 1860 there were 150 families resident on Chincoteague, 126 oystermen on the island, and others belonging to allied trades. That year, a hotel was operating on the island, located in what today is the downtown area—in the mid-19th century, that part of the island developed as Chincoteague's commercial core.[15]

The first accounts of pony penning are from an 1835 letter to the editor published in the Farmer's Register by Thompson Holmes of "Chincoteague"—that is, the mainland opposite the island, then also called by that name. According to his letter, few horses remained wild on Chincoteague Island, and residents would go over to Assateague to build temporary corrals to place the local herds in. Selected horses were branded, gelded, and sold. Holmes told about an earlier practice, to drive the horses directly into the water, which had been abandoned because too many had drowned. Holmes mourned that the pony pennings of his day were only "a shadow of their former glory".[16] The pennings, the letter related, nevertheless attracted crowds from far and near.[17]

Civil War (1861–65)

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 left Chincoteague residents with a stark choice. If they left the Union as Virginia sought to do, they might lose access to their seafood markets. Refusal to do so might isolate Chincoteague from the rest of its state. In the referendum on secession held in Virginia on May 23, 1861, Northampton County, in the southern Eastern Shore, voted unanimously for secession, and there was also a majority for leaving the Union in Accomack County. Nevertheless, the residents of Chincoteague, along with those on Tangier Island (part of Accomack) in the Chesapeake Bay, chose not to leave the Union, in Chincoteague's case by a vote of 134 or 135 to 1 or 2—sources differ as to the exact tally. Despite this lopsided tally, some from Chincoteague supported the South, or even fought for it.[18]

Even before the vote, commerce between the North and Virginia had been forbidden by Union officials. Residents sent John A.M. Whealton, a merchant and staunch Union loyalist, to Philadelphia to seek the release of confiscated supplies. He was able to gain the support of local officials and sailed cautiously for home with the goods, aware that the permission of Philadelphia's mayor did not bind the U.S. Navy. He found the Assateague Lighthouse extinguished by southern sympathizers and the bay again used for smuggling. In September, the USS Louisiana, an ironclad, arrived, with orders to secure the area against smugglers, and within days, one smuggler's ship was burned in the engagement known as the Battle of Cockle Creek, and another captured two days later. The naval vessel received a warm welcome from the islanders, who promptly took oaths of allegiance to the Union. After a petition on behalf of 800 inhabitants of the island was passed up the chain of command, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles granted the islanders the right to continue to engage in trade in November 1861, the same month the Eastern Shore was taken for the North with little bloodshed.[18]

The Louisiana was sent away to more troubled waters in December 1861, arousing fears by the islanders that they would be abused by Confederate loyalists on the mainland. There were some incidents of this sort, but they ceased as the mainlanders adjusted to the military presence, and the war did not again come near Chincoteague. Union soldiers were stationed on Chincoteague Island for about four months in 1863 and 1864 to guard against a rumored attack on Assateague Lighthouse by sympathizers. Maryland militia were initially used, followed by a regiment of African-American soldiers, but in March 1864, they were removed and local men in the Eastern Shore Volunteers, formed in 1863 but not called into service until the following year, guarded the island and other local points.[19]

Postwar prosperity (1865–1908)

The years after the Civil War brought prosperity to Chincoteague with expansion of the oyster trade. As the law required an oysterman to be a Virginia resident for a year before harvesting in Virginia waters, many in that trade bought lots along Main Street, running along the west side of the island, or across the bay in the new village of Greenbackville, Virginia, just south of the Maryland line. Other new residents on the island were freed African-Americans, or Northerners who sought opportunities in the southern states.[20] Chincoteague oysters, especially those from Tom's Cove at the southern point of the island, gained a reputation for taste, and, marketed across the country as "Chincoteague salt oysters", became famous.[21][22]

In 1876, art student Howard Pyle visited Chincoteague. He wrote of his experiences, including viewing the pony penning (which took place behind his hotel), the following year in Scribner's Magazine, accompanying the text with the first known contemporary drawings of the event.[23] Pyle was struck by the quaintness of Chincoteague, describing it as "an enchanted island, cut loose from modern progress and left drifting some seventy-five years backward in the ocean of time".[24] The publicity in a national magazine did nothing to reduce the crowds coming to Chincoteague for the penning.[23]

The island's status as an isolated backwater began to end in 1876, when a rail line reached Franklin City, on the shores of the bay and only 5 miles (8.0 km) from Chincoteague Island, with a steamship supplying the remaining connection. This improvement gave oystermen an efficient means of getting their wares to market, and also brought early tourists to Chincoteague, seeking respite from the sweltering summers in the city.[21]

Due to the popularity of oysters, Chincoteague continued to grow; commercial buildings were built along Main Street. In 1890, the island acquired its first barbershop, and about 500 barrels of shucked oysters were being sent to the mainland daily on the steamer. Gas illumination arrived by 1900, the first telephone exchange in 1902, and rural free delivery by the United States Post Office Department in 1905.[25] Although there were few shops or public buildings, there was a shoe store and a notary public. The roads were made of dirt, covered with sea shells.[26]

Entering the modern era (1908–46)

In the early 20th century, according to Mariner, Chincoteague "was a curious mixture of the progressive and the primitive, of worldly-wise townsfolk and isolated country people".[27] Beginning in about 1900, the residents sought to be incorporated as a town. Gaining a municipal charter from the General Assembly would allow ordinances to be passed to keep livestock off the streets without seeking redress from the state government in Richmond or the county government in Accomac. In 1908, the legislature incorporated part of the island as the Town of Chincoteague, and on July 4, A. Frank Matthews became the first mayor.[28]

The 1910 United States Census showed a population of 3,295 for the island, of whom 1,419 lived in the town. Few resided in the interior of the island; most lived in single-family houses, facing the water across roads that ran just above the high tide line. The population of the island had increased to about 3,600 as of 1916; there were about 100 African-Americans, all of whom lived on the same part of the island. Most islanders of working age were part of or supported the seafood trade. At that time, most houses got their water from shallow-dug wells, located in many cases close by primitive privies. Water from such wells was also used to wash the oysters and to make ice to preserve them. Almost all Chincoteague oysters were sent out of state, and the federal Public Health Service intervened in 1916 to get the mayor and town council to order improved sanitation, with islanders living outside the town line agreeing to abide by the ordinances.[29]

Although dwarfed in population by the neighboring island, Assateague was still populated by a few families. A penning was still held on Assateague along with one on Chincoteague, but the Assateague event was suspended after 1920 as the largest landowner refused to allow access. Beginning in 1923, the Assateague herd was transported to Chincoteague for a joint penning, most likely by boat, as the idea of swimming the ponies had not yet been adopted.[30] The refusal of the Assateague landowner to allow islanders to cross his land made it difficult for them to get to work, and Assateague became depopulated, with most of the buildings disassembled and rebuilt on Chincoteague Island. Most of Assateague Island was sold to the federal government in 1943.[31]

In 1919, John B. Whealton, Chincoteague-born though a Florida resident, persuaded the Virginia General Assembly to grant a charter to his Chincoteague Toll Road and Bridge Company to build a causeway from the mainland to the island. Whealton submitted the winning bid to build the causeway as well as gaining the charter for his company to operate it. The road was originally a toll crossing, and early plans had it reaching the island south of downtown, near the site of today's Carnival Grounds, but Whealton persuaded the town council to have the terminal point be downtown, near the Atlantic Hotel, the island's largest. The road was close to completion when a major fire destroyed much of downtown, including the hotel, on February 5, 1920. There was then only a small, ill-equipped fire company in Chincoteague, and the fire was fought by men of the Coast Guard from the stations near the island. The hotel was underinsured and not rebuilt, though others took its place, and the council took advantage of the disaster to straighten Main Street. The fire and poor weather in the winters of 1921 and 1922 delayed the causeway, which was officially opened on November 15, 1922, by Virginia Governor E. Lee Trinkle. Most vehicles on the first day wound up mired in mud once a downpour turned the causeway into a quagmire. Nevertheless, the causeway proved a success, and by year's end over 100 vehicles were crossing it on an average day.[32] Water from mainland wells was piped along the causeway, allowing the town to offer running water.[33]

The second devastating fire in four years destroyed much of downtown Chincoteague on February 25, 1924, and caused the town's leaders to conclude that a better-organized volunteer fire department was needed to replace Chincoteague's fire brigade. The Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company was founded in June 1925, though it needed much equipment, including a fire truck.[25] To raise funds the fire company took over the 1925 Chincoteague pony penning, which had been declining, and sold some horses at fixed prices (auctioning began not later than 1932). Fifteen thousand people attended the penning and other festivities. The proceeds from the event were over $6,000, enabling the department to buy a pump truck. Public fascination with the pony swim, inaugurated that year at the narrowest point of the channel between the two islands, led to increased attendance in the following years.[34] Except during the war years of 1943 and 1944, the carnival, pony swim and auction have occurred every year since.[25]

By 1930, the year the causeway was purchased by the state and the toll removed, the Town of Chincoteague had a population of 2,130.[33] In the 1930s, poultry farming became popular on the island, and by the 1950s, produced over a million birds per year.[35] Although oystering was still a common occupation, the trade was increasingly regulated, causing much of the production and canning to be done by large companies, and many watermen turned to fishing, clamming, and crabbing. Others shot ducks and other waterfowl indigenous to the island. Locals carved duck decoys to aid in the hunt; these remain a popular collectible and souvenir of the island.[36]

In 1941, the United States entered World War II; early the following year, the Germans torpedoed two merchant ships off the Assateague coast. To guard the coast, the United States Army established two small posts on Virginia's Eastern Shore, one each at Accomac and Chincoteague. The Navy established the Chincoteague Naval Auxiliary Air Station in 1943, across from Chincoteague on the mainland. One young pilot being trained there, future president George Herbert Walker Bush, got in trouble for "buzzing" the house of a young woman he had met at a dance. The conclusion of the war, in 1945, brought celebrations in Chincoteague and the reinstatement of the annual July events, now held at the brand-new Carnival Grounds south of downtown.[37]

Misty and changes (1946–62)

In 1946, children's author Marguerite Henry came to Chincoteague for the summer, intending to write about the wild horses of Assateague and the pony penning and auction on Chincoteague Island.[38] With her came illustrator Wesley Dennis, with whom she had previously worked, and who would take photographs to be converted to pen-and-ink drawings.[39]

Staying at the bed and breakfast of Miss Molly Rowley on Main Street, Henry encountered island horse breeder Clarence Beebe, visited his ranch on the southern portion of the island, and met his grandchildren Maureen and Paul. On the Beebe Ranch, Henry saw a young filly named Misty. Henry fell in love with the horse, and tried to persuade "Grandpa" Beebe to sell the filly, promising to include him and his grandchildren in her book. The breeder eventually agreed, on condition Misty remained on the Beebe Ranch until she was weaned, and that the animal was eventually returned to him from Henry's Illinois home for breeding. Henry made the purchase, and returned to the Midwest with an outline of her story. Several months later, Misty arrived by rail. In 1947, Henry's book Misty of Chincoteague was published, about the desire of the Beebe children to have a pony of their own—Misty, daughter of the untamable Phantom. The book became an immediate best seller, and the following year was designated as a Newbery Honor Book by the American Library Association.[38] Following the book's appearance and success, a steady stream of articles on Chincoteague began to appear in national magazines.[40]

Henry wrote a series of sequels, and hoped to interest the movies, but Hollywood was slow to reach out to the Eastern Shore. It was not until 1960 that filming of Misty began. Almost all of the motion picture was shot locally—though the Beebe Ranch was not used, with a property on the mainland substituted. The film premiered at a Hollywood cinema and at the Roxy Theatre in Chincoteague, with the first showings simultaneous. In a nod to Hollywood, the real-life horse Misty placed her hoof in wet cement outside the Roxy just before the movie ran.[41]

Despite the new source of island fame, many young people left Chincoteague in the years after World War II. There was no beach on Chincoteague; in an effort to provide one for visitors and townsfolk, local promoters sought the construction of a bridge to Assateague Island, where there is a beach along the Atlantic shoreline. They were led by Wyle Maddox, a wealthy chicken farmer who had significant business interests on Chincoteague Island. First proposed around 1950, the bridge and roadway across Assateague, by then uninhabited and under federal jurisdiction, took over a decade to approve, and finally opened in September 1962. The bridge to Assateague is at the east end of Maddox Boulevard, that crosses Chincoteague Island north of downtown, and was developed by Wyle Maddox.[42]

The town remained busy and prosperous in the postwar years, especially by the standards of the rural Eastern Shore, and the locals took pride in this—in the early 1950s, the town twice finished second in a competition for the cleanest community in America, and then won the award for its size classification in 1954 and 1955. Main Street was so crowded with cars that parking meters were installed. When oyster parasites and overfishing combined to devastate the oyster industry in the 1950s, clams became the island's major industry. The Burton Clamming Company promoted itself as the largest in the world, sending 1.3 million clams to market on a typical day in 1957.[43]

The final delay in the completion of the Assateague bridge was caused by the Ash Wednesday Storm of March 1962 that devastated both islands, as well as other points along the Atlantic Seaboard.[44] Although no one died on Chincoteague,[lower-alpha 2] the storm flooded virtually all buildings on Chincoteague Island and wiped out the poultry industry—not only were an estimated quarter million birds killed, the buildings used in chicken farming were destroyed. An estimated 100 ponies were killed by the storm, both on Assateague Island and at the Beebe Ranch. Misty was pregnant with her third foal; the Beebes placed her in their kitchen before they were evacuated. Once the ranch could again be reached, Misty was taken to a farm on the mainland just over the Maryland line, where she gave birth to a filly, Stormy. The devastation of the storm brought national attention to Chincoteague, and Stormy's birth upstaged the visit of Virginia Governor Albertis S. Harrison. Many contributed to the recovery efforts, and Misty—both film and horse—was made available for special benefit showings.[45]

Tourist destination (1962–present)

Until the 1950s, most tourists to the island, except during the annual carnival and pony penning, were sportsmen, there to fish or hunt waterfowl.[46] Publicity generated by the Misty franchise, and the easy access to the beach and recreational facilities on Assateague Island, brought many tourists to Chincoteague who were uninterested in shooting the wildlife except with cameras. Combined with the continued decline of the seafood industry, the economy of Chincoteague gradually shifted from being based on harvesting its waters to tourism.[47]

Many souvenir shops and other tourist enterprises were built along Maddox Boulevard,[48] especially in the years after 1962.[49] At first, the motels were buildings converted from other uses, but by the late 1960s, purpose-built structures were being erected along Maddox Boulevard, some with swimming pools.[50] Although Misty died in 1972 at age 26,[51] the island continued to be publicized. By the 1990s, tourism was the island's principal business, bringing in more than $100 million annually. National hotel chains, including a Hampton Inn and a Comfort Suites, arrived with the 21st century.[52]

The changes to Chincoteague, including the sale of the Beebe Ranch for development in 1989 and the destruction by fire of the ranch house in 1996, brought local soul-searching. Islanders were divided by such questions as the establishment of a nudist beach on Assateague (outlawed by Accomack County ordinance in 1984) and the building of a McDonald's near the bridge between the two islands. The modest homes on Chincoteague Island were supplemented by townhouses and condominiums, many occupied by seasonal residents. With increased real estate prices, many from Chincoteague sold their land and moved to less expensive property on the mainland. The seafood industry ceased to be a major factor in the island's economy: most of the oyster-shucking houses, which had continued in operation using imported shellfish despite the local decline in oystering, finally closed in the 1980s and 1990s. The clam industry sought bivalves from deeper waters, and Chincoteague by then supplied few shellfish.[53]

In 1989, the town expanded, by agreement with the Accomack County government, bringing all of Chincoteague Island under town jurisdiction. Despite local opposition, the modest bridge between Chincoteague and Assateague was rebuilt into a four-lane structure in 2010, the better to accommodate the millions of annual visitors to Assateague. The causeway from the mainland was re-routed, moving the terminal point on Chincoteague Island to a point north of downtown, the intersection of Main Street and Maddox Boulevard. From there, visitors may proceed south to downtown and the Carnival Grounds, or east to the tourist strip along Maddox Boulevard and to the bridge to Assateague Island.[53] The tourist stores on Maddox Boulevard sell souvenirs, local artwork, the necessities for a day at the beach, and pony-related T-shirts and books.[48] As of 2009, the average foal at the auction sold for $1,344. Between 60 and 80 are sold annually; the auction helps keep the herd at a sustainable population of 150.[51] In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the pony swim and associated events were canceled.[54] James Tigner Jr. wrote in his 2008 book about Chincoteague Island,

In the book and in real life, the story of Misty is really of those who loved her unconditionally. For that reason Misty today is a symbol for all that is wonderful and beautiful ... From my visits I know that much of the good that Misty represents can still be found on her little island of Chincoteague.[48]

See also

- Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, Assateague Island

References

Explanatory notes

- At that time it was often spelled Accomac, the name still borne by its county seat. The county was officially designated as Accomack by the Virginia General Assembly in 1940.

- Two Marylanders died when their boat was grounded on Assateague Island south of the state line; one evacuated man died of a heart attack at a mainland hospital. See Mariner, p. 142

References

- Amrhein, pp. xx–xxi.

- Cumming, pp. 25–26.

- Mariner, p. 4.

- Mariner, pp. 10–11.

- Mariner, pp. 12–14.

- Tigner, p. 7.

- Amrhein, p. xxi.

- Amrhein, pp. xxi–xxii.

- Mariner, pp. 18–19.

- Camagna & Cording, p. 4.

- Mariner, pp. 22–23.

- Mariner, pp. 25–28.

- Mariner, pp. 31–33.

- Camagna & Cording, p. 5.

- Mariner, pp. 41, 46.

- Mariner, p. 39.

- Camagna & Cording, pp. 4–5.

- Mariner, pp. 46–54.

- Mariner, pp. 54–57.

- Mariner, p. 59.

- Tigner, pp. 7–8.

- Camagna & Cording, pp. 5, 10.

- Mariner, pp. 70–74.

- Pyle, p. 738.

- Tigner, p. 8.

- DeVincent-Hayes & Bennett, p. 29.

- Mariner, p. 94.

- Mariner, pp. 95–96.

- Cumming, pp. 26–29.

- Mariner, pp. 95–104.

- Camagna & Cording, p. 44.

- Mariner, pp. 105–113.

- Mariner, p. 125.

- Mariner, pp. 116–117.

- DeVincent-Hayes & Bennett, p. 85.

- Mariner, pp. 117–120.

- Mariner, pp. 129–130.

- Tigner, p. 13.

- Mariner, p. 136.

- Mariner, p. 137.

- Mariner, pp. 138–139.

- Mariner, pp. 135, 140–144.

- Mariner, pp. 132–134.

- Tigner, p. 14.

- Mariner, pp. 141–144.

- Mariner, p. 135.

- Camagna & Cording, pp. 18, 20.

- Tigner, p. 18.

- Camagna & Cording, p. 28.

- Mariner, p. 46.

- Fried.

- Mariner, p. 146.

- Mariner, pp. 145–154.

- "Chincoteague pony swim and 2020 carnival canceled due to COVID-19". WMAR. May 19, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

Bibliography

- Amrhein, John Jr. (2007). The Hidden Galleon. Kitty Hawk, NC: New Maritima Press. ISBN 978-0979687204.

- Camagna, Dorothy; Cording, Jennifer (2004). Chincoteague Revisited: A Sojourn to the Chincoteague and Assateague Islands. Richmond, VA: The Oaklea Press. ISBN 1-892538-11-3.

- Cumming, Hugh S. (March 1916). "Investigation of the pollution of tidal waters of Maryland and Virginia". Public Health Bulletin. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office (74).

- DeVincent-Hayes, Nan; Bennett, Bo (2000). Chincoteague and Assateague Islands. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadis Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0562-5.

- Fried, Kerry (June 18, 2010). "Where the wild ponies swim". Parade: 12.

- Mariner, Kirk (2010) [1996]. Once Upon an Island: The History of Chincoteague (3rd ed.). Onancock, VA: Miona Publications. ISBN 0-9648393-3-4.

- Pyle, Howard (April 1877). Chincoteague: The island of ponies. Scribner's Monthly. pp. 737–746.

- Tigner, James Jr. (2008). Chincoteague Island. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7643-2919-7.

Further reading

- Pleasants, Bernie (1999). Chincoteague Pony Tails. Columbus, GA: Brentwood Christian Press. ISBN 1-55630-905-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Chincoteague, Virginia. |