Historical murders and executions in Stockholm

Murders and executions in Stockholm, Sweden have been documented since the 1280s, when King Magnus Ladulås ordered the execution of three magnates of the Privy Council, who had been accused of several "traitorous acts against the throne". The city's murders between the middle of the 15th century and the middle of the 17th century have been documented fairly well in the logs of the Stockholm City Court. Violence with a deadly outcome was most common during the Middle Ages, a trend which had more than halved by the beginning of the 1700s. The most common cases of manslaughter and murder usually involved fights between men where alcohol was involved.

During the reign of Gustav III, the use of capital punishment decreased and was abolished for certain crimes. The last hanging took place in 1818 at Hammarbyhöjden, and the last public execution occurred in 1862. The last execution in Sweden and Stockholm took place on 23 November 1910, when robber and murderer Alfred Ander was executed by decapitation in a guillotine.

Stockholm has experienced a remarkable number of political murders, and the most notable group of cases is the Stockholm Bloodbath between 7 November and 9 November 1520, when parts of the royalty and the nobility desired to get rid of several of their competitors and critics. Two highly acclaimed murders of politicians during recent years include the assassination of Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1986 and the murder of Anna Lindh in 2003. Additionally, several terrorist attacks have occurred in the city, namely the West German Embassy siege in 1975, the 2010 Stockholm bombings and the 2017 Stockholm attack.

Cases of murder and manslaughter have not increased in the past 250 years.

The Middle Ages

Murder and manslaughter among the populace

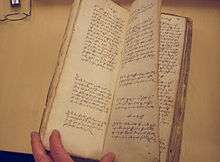

According to the Stockholm tänkeböcker, it is fair to assume that violence with a deadly outcome was up to a hundred times more common during the Middle Ages compared to today.[2] Usually, most cases of manslaughter involved two intoxicated men fighting each other, resulting in either party's death. If the surviving party were to report the event and turn himself in, his punishment would be less grave. Murder was a more serious crime, especially if the perpetrator would attempt to hide the fact.[3]

The Käpplinge Murders

Hostility between German merchants and the populace of Stockholm led to the so-called Käpplinge Murders. On 14 June 1389, German hättebröder, soldiers and merchants marched towards Stortorget and gathered near Kåkbrinken. The Germans read aloud a list of the names of 76 Swedish "traitors" who were to be taken into custody. A number of them were locked inside Tre Kronor Castle, and others were taken to Gråmunkeholmen (Riddarholmen). The captives were tortured with saws. On 17 June the prisoners inside Tre Kronor castle were ferried over to Käpplingeholmen (Blasieholmen) where they were locked inside a building which was set on fire. The smallest number of victims of the Käpplinge Murders was noted as 15, the highest was 76.[4]

Medieval legislation

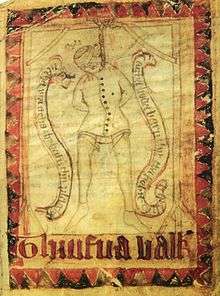

A quite harsh legislation composed of the Magnus Erikssons stadslag and Magnus Erikssons landslag, which made the death penalty legal for thieves still did not manage to deter criminals. 140 persons were executed between 1474 and 1492 in Stockholm. 50 persons had been convicted of violent crimes such as manslaughter, murder and assault. 90 were thieves and robbers. The chapter addressing thievery in Magnus Erikssons landslag is introduced with a picture depicting a hanging. The text promotes corporal punishment against children in order to prevent them turning into criminals.[5] A human life was not worth much during the Middle Ages. If Sweden were to exercise the death penalty at the same level today, around 1 560 persons would be executed yearly, or four people daily.[6]

Fights and honor

The most common incidents were fights between two men who were usually intoxicated. The most common murder weapon was a knife, as almost every man carried one. Less common weapons included wooden logs, stein (beer mugs), axes, hammers and furniture.[6] Insulting ones honor could also be a justification to deadly violence. A third of all cases of murder and manslaughter during the 1500s usually involved honor-related conflicts.[7] Minor conflicts sometimes triggered murder. On 9 June 1589, a knight known as Anders was accused of the murder of the farmhand Bengt Persson. They had been shooting darts and when Anders missed the target, Bengt mocked him by whistling. This was enough for Anders to draw his knife and stab Bengt in the head. The court ruled that a murder for such a minor reason was not right and therefore sentenced Anders to the death penalty.[8]

Some of the courts sentences are today difficult to comprehend. Persons who committed murder or manslaughter were not always sentenced to death, an example would be when a flayer known as Henrik was charged with manslaughter on 18 June 1492 for killing his servant. But Henrik was later freed from all charges since it turned out that the servant was envious of Henrik, which was considered sinful. On 17 December 1498, Klas Larsson from Utsunda village was accused of murder. He was sentenced to death, simply because the jury stated that they could see in his eyes that he was guilty.[9]

Political murders

Besides murder and manslaughter among the general population, political murders were not uncommon occurrences in Stockholm. The most common cases were politicians who desired to get rid of competitors or punish critics. The oldest documented cases of this category goes back to 1280, when King Magnus Ladulås ordered the execution of three members of the privy council, who had been accused of several "traitorous acts against the throne".[10]

Another notable case is the execution of Torkel Knutsson on 10 February 1306. After being sentenced to death, he was killed by decapitation on Pelarbacken (Götgatsbacken) and buried in Grey Friar's Abbey. The capture and subsequent execution of Torkel was the result of an agreement between King Birger Magnusson and his brothers in order to stop Torkels dominance of the government.[11]

Magnus Birgersson, son of Birger Magnusson, did not die a natural death either. He was a prince and was capable of threatening the throne. On 21 October 1320 he was sentenced to death and executed a week later at Helgeandsholmen. He received an honorable funeral at Riddarholm Church.[12]

The knight Broder Svensson Tjurhuvud was forced to pay with his life in 1436 after he had publicly expressed his dismay against the king. He had insulted King Charles VIII with harsh words, when he had not received a castle as a fief. He was arrested and executed on Brunkebergstorg.[13]

Betrayal against the king was not acceptable either and was punishable by death. Måns Bryntesson Lilliehöök, one of Sweden's most eminent men in the 1520s, suffered the death penalty in 1529 when he participated in the Westrogothian Rebellion against King Gustav Vasa. The rebellion failed, and the king offered Lilliehöök mercy. But, in his belief that all evidence incriminating him had been destroyed, Lilliehöök declined and demanded that a trial be held. Authorities did have evidence, and in 1529, the Riksdag at Strängnäs sentenced him to death. Lilliehöök attempted to escape custody, but fell and broke his femur. After crawling his way out of the city, he was found hiding in a field. On 7 September 1529, Lilliehöök was executed by decapitation on Södermalmstorg. His head was impaled on a spear and his body was buried at Riddarholm Church.[14]

In some cases, kings have personally murdered people. In 1568, King Eric XIV beat his secretary Martin Olai Helsingius to death with a stove poker. Martin had allegedly advised the king against pardoning his former secretary Jöran Persson,[15] who was a very trusted advisor and friend of the king, but whom the Swedish people despised. Persson had been accused of causing the looting of Svartsjö Palace in 1567 and the Sture murders the same year. He received his verdict on 28 September 1568 and was punished "as an honorless, faithless and perjurous traitor, rogue and villain". Martins punishment was cruel. Both of his ears were nailed against the gallows, along with his patent of nobility. He was later hinged onto the gallows, but before his death he was brought down again. and subjected to breaking wheel torture at Brunkebergstorg. He was eventually beheaded and his body was nailed to a stake, where his body could be observed in public. This was a regular practice during the Middle Ages in Sweden, until it was outlawed in 1841.[16]

Stockholm Bloodbath

The largest group of political murder cases in Stockholm is undeniably the Stockholm Bloodbath, which revolves around the looting and subsequent executions between 7 November och 9 November 1520. The events took place three days following the coronation of Christian II as King of Sweden. when the coronation party guests were called to a meeting at Tre Kronor Castle. Archbishop Gustav Trolles demands of economic compensation for the demolishing of his castle led to the question if the previous regent Sten Sture the Younger and his followers should be found guilty of heresy or not. Supported by canon law, approximately 82 persons were executed during the following days. The executions were performed on Stortorget and commenced in the afternoon of 8 November with the beheadings of bishops Mattias och Vincent. 15 members of the nobility were thereafter also beheaded by sword, thereafter the mayor of Stockholm along with his advisors were killed by hanging. On 9 November, the servants belonging to the now executed parts of the nobility were also executed. Bonfires were lit on Södermalm in the same area where Katarina graveyard would be laid out on 10 November. The grave of Sten Sture the Younger in the Black Friars' Monastery was dug up and thrown in the bonfire on Pelarbacken.[17] The events were immortalized in 1524 on Blodbadstavlan (literally "The Bloodbath Painting") which also contains one of the oldest known depictions of the city of Stockholm.

Swedish Empire

Between the middle of the 1500s and the middle of the 1700s, the punishment had grown harsher both in the rest of Europe and in Sweden, but after the middle of the 1700s, the trend aimed towards milder forms of punishment. It would appear that the breaking points towards harsher punishment was the Protestant Reformation, while the Age of Enlightenment involved tendencies towards milder forms of punishment.[18]

During the entirety of the 1600s and the rule of Swedish Empire, the number of deadly crimes committed decreased. The amount of crime compared to the size of the population in the Stockholm area decreased by over 90 percent between 1600 and 1750. It is unclear whether or not this reduction was caused by harsher legislation.[19]

One possible explanation could be the wars of Sweden. In the beginning of the 17th century, around 30 percent of all cases of murder and manslaughter were committed by Swedish soldiers in Stockholm. When these soldiers were on the battlefield, however, deadly crime occurrences showed a steady decline. A lot of men died, and the number of young, aggressive men roaming the streets decreased.[20] Additionally, fires and local epidemics occurred.[21] In 1635, the city government started hiring guards who were tasked with patrolling public places and maintaining order. In 1667, there were over 70 official city guards, the city guard was a predecessor to the Stockholm police. It is probable that the guards contributed to the decrease in violence.[20]

17th century

Murder and manslaughter was still the most common reason for the use of capital punishment. Sometimes, an executioner would have to execute another executioner:[22]

Executioner Mikael Reissuer (also known as Mäster Mikael) was executed on 20 March 1650 by his successor. Mäster Mikael exercised his practice at a designated execution spot in Södermalm from 1635 until his death in 1650. Mikael killed his friend, Påwel Andersson in 1650 following an argument about a debt. Mikael plead not guilty and stated that Påwel had "accidentally run into the edge of Mikael's sword". The court did not believe him and he was sentenced to death and executed by his successor.[23]

The well-known poet Lasse Lucidor (his real name was Lars Johansson) also known as "the unlucky one" was just 36 years old when he got caught in a melee battle on the night of 12 August 1674 and was pierced by Lieutenant Arvid Kristian Storm's sword. The murder took place in the basement of today's Kindstugatan 14 in Gamla stan. These armed conflicts, or so called "duels" were usually the result of trifles combined with alcohol. Lucidor had gotten into a fight with the bartender who had refused to continue serving him wine unless he paid for it. In an attempt to disrupt the commotion, army Lieutenant Storm approached Lucidor, at which point Lucidor drew his sword and scratched Storm's hand. Storm drew his own sword and stabbed Lucidor. Lucidor was buried in an unmarked poor man's grave in the north end of Maria Magdalena graveyard. Storm was charged with manslaughter on 22 August 1674, but managed to escape custody with the help of his mother, presumably to flee the country.[24]

Vercits from the 1400s may seem odd today. But in the 1600s, authorities started operating in a similar way as police investigations and trials look like today. Crimes were reconstructed and witnesses were interviewed. The following example is a court case from April 1626 which can help illustrate the Swedish legal system at the time.[25]

A man had been found brutally murdered on a location known as 'Häägersteen'. The authorities quickly asked the public for help, and called for the murderer to turn himself in, which he did not. A citizen claimed that the victim was a Hans Putestad, an unemployed tailor who had travelled to a farm in Ekerö to meet with shoemaker Hans Schechtelfocht. Putestad was known for bringing his entire life savings with him, by sewing them directly into his clothes. Upon further inspection, no money could be found in his clothing. Scechtelhocht was apparently the farmowners gardener and was taken in for interrogation. Schechtelfocht stated in front of the court that he had offered the tailor employment, and had not heard from him since.[26]

Schechtelfocht had apparently not had enough time to change clothes, he had blood on his shirt. Schechtelfocht stated that he had a nosebleed, even though the blood was only visible on the back of his shirt. The court deemed him suspicious and looked into his story. The persons who had discovered the body could confirm that Putestads pants had been replaced, this made the court believe that Schechtelfocht must be in possession of the victims real clothes, and in turn, his money. Schechtelfocht constantly changed details of his story and the court eventually told him to give up the truth, or his soul would be taken by the devil. He was found guilty of the murder of Hans Putestad and was executed.[26]

18th century

During the Age of Enlightenment, the trend in Europe started aiming towards milder forms of punishment.[18]

Stockholm in the 1750s is described as a calm city with kind and welcoming citizens. A secretary of the court chancellery stated that Stockholm had been transformed into a city with extraordinary standards of order and morality. The fact that Stockholm still was quite a small city compared to other European capitals, where everyone knew everyone may have contributed to this.[27]

The citizens of Stockholm also generally avoided leaving their homes at night, as Stockholm was quite a dark city at night in the 1800s. Torches and other open sources of light were prohibited due to the fire risk, and persons who wished to leave their houses were reminded to not forget their lanterns.[28]

Stockholm operated an effective guards force which consisted of 148 official guards by 1720.

In 1776, Kungliga Poliskammaren (literally The Royal Police Chamber) was established with its headquarters located within the Tessin Palace. The Police Chamber was to be overseen by the Governor of Stockholm and was tasked with issuing city regulations and laws regarding public order, as well as handling petty crime court cases.

At the end of the 1700s, cases of deadly violence were considered rare in Stockholm, and the ratio of murder and manslaughter cases per citizen was just 2 per 100 000 annually. Thus, the ratio was not higher then, than it is in today's Stockholm.[29] Of all violent crime cases of the 18th century, roughly more than half were cases of infanticide.

Punishment was still relatively harsh, even though torture had been abolished under Gustav III. He had closed the infamous Rosenkammaren (literally: 'The Rose Chamber'), and was known for despising the death penalty and using all means necessary to change sentences or, in some cases, pardon felons. According to statistics, hanging was never used as capital punishment during the reign of Gustav III. Hanging was considered the most humiliating manner of death, and was often used on thieves and forgers. Beheading by sword, however, held a higher status.[30]

The Assassination of Gustav III

Even though Gustav III was known as "the mild monarch" at the time, he was the victim of an assassination attempt on 16 March 1792, which led to his death thirteen days later.

Gustav III and the nobility had gone through numerous disputes during his reign. Parts of the nobility did not approve of the King cutting their privileges. Other parts did not agree with his politics, and certain parts simply had personal grounds for hatred against Gustav III. This led to a conspiracy against his life, led by Jacob Johan Anckarström, whose goals were both personal and political.[31]

Anckarström, along with Carl Fredrik Pechlin, Adolph Ludvig Ribbing, Clas Fredrik Horn af Åminne, among others, conspired together against the King at Huvudsta gamla slott. Gustav III's own theater, Gustavianska operahuset was chosen as the crime scene.

On 16 March 1792, Anckarström entered the theater during a masquerade, which granted him inconspicuous concealment, and shot Gustav III. The bullet was fired at close range and hit the King in the back, near his left hip. The King's company, a member of the Von Essen family, immediately ordered all exits to be closed, and Polismästare Nils Henric Lilljensparre had all party guests demasked and their names noted. Anckarström was arrested the day following the murder.

Gustav III did not die instantly, but instead continued to function as head of state, until his wound became infected which he died from thirteen days later, on 29 March. Unaware that he was dying, he gave the order that the lives of all 40 persons involved in the conspiracy were to be spared, except for the murderer.[32]

Anckarström was sentenced to public humiliation and the death penalty. His right hand was cut off, he was publicly whipped for three days on Riddarhustorget until he was beheaded on 27 April 1792. Parts of his body were nailed to the execution spot, as part of tradition.

An entire family, sentenced to death

In 1756, Maria Rial Guntlack, together with her lover Johan Wilhelm Falcker, poisoned her husband Abraham Guntlack. Falcker's punishment was the decapitation of his right hand followed by his beheading on 16 July 1756. Maria Rial received similar punishment, with the exception of her burning on 21 February 1757. Owing to her being pregnant with Falcker's child, the execution had to be postponed for a few months. Abraham and Maria's firstborn son Jacob Guntlack was 12 years old when his mother was executed. Jacob would grow up to become a thief and swindler. He was sentenced to death on four occasions, but managed to escape custody three times. In the fall of 1769 he was recaptured and finally executed on 16 January 1771. He spent the two years prior to his execution writing his biography, while imprisoned at Nya smedjegården.[33]

The biography was supposedly written by Jacob himself, but no proof has been presented to support this. The book was widely famed at the time and was translated into other languages.[34] Guntlack was executed on 16 January 1771 in public.

Cases of infanticide in the 18th century

Between 1751 and 1765, 138 people were executed for infanticide while 132 persons were executed for murder.

The average killer of a child at the time was generally a young woman in her late 20s who did not have either the will nor the means to keep the child.[35]

Usually, if the victim was an infant, the mother would state that the child was a stillborn, such was the case in the winter of 1765 when a Brita Engström was suspected of the crime. Her neighbors had noticed that Brita had grown fatter and then suddenly she was very thin. Brita confessed that she had in fact had a child, but it was a stillborn. But when the authorities examined the corpse of the infant, they found evidence that the infant was alive at the time of its birth. The infant's neck had blue bruises which indicated that it had been strangled. Simson, the father, stated that he did not know anything, even though he and Brita lived together. The court did not believe the couple, and Simson was sentenced to 14 days in prison, while Brita was sentenced to death.[36]

In order to combat the issue, Gustav III passed the Infanticide Act in 1778, a law which allowed unmarried mothers to give birth anonymously. Nurses were now prohibited from asking for the name of the father. The idea was to prevent infanticide by letting the woman travel to another town and give birth there instead of having to state her name.

Under the law, the death penalty was abolished for unintentional infanticide.[37]

19th century

The death penalty was abolished for certain crimes during the reign of Gustav III, and pardons were more frequently issued. During the 19th century, the use of pardons increased even more, and starting in the middle of the 1800s, courts were officially permitted to pick between the death penalty or lifetime in prison.[38]

The last hanging at Hammarbyhöjden occurred in 1818, and the last public execution at Hammarbyhöjden took place in 1862 when Per Viktor Göthe was beheaded for the rape and murder of Anna Sofia Forssberg (read more below).[39] Public executions were abolished entirely in 1877, and in 1890 the last execution of a woman, Anna Månsdotter, took place for her participation in the infamous Yngsjö murder.[37]

Lynching of Axel von Fersen

The bloody 19th century in Stockholm starts with the lynching of Marshal of the Realm Axel von Fersen on 20 June 1810 outside of the Bonde Palace in Gamla Stan. The story behind the event could be seen in the political disorder which occurred following the death of Gustav III and the exile of his heir Gustav IV Adolf. As Marshal of the Realm, von Fersen had a close relationship with Gustav III, and was subsequently beaten to death by an angry mob, following the death of the new Crown Prince Charles August. The guards posted outside the palace did not intervene.

Axel von Fersen and his sister Sophie von Fersen were Gustavian loyalists, who sought to install the exiled Prince Gustav, son of Gustav IV Adolf as Crown Prince. When Crown Prince Charles August suddenly died of a stroke in 1810, the position was yet again vacant. The parts of the nobility who had exiled Gustav IV Adolf did not wish to see the exiled King's son as successor. When Charles August died, rumors were spread regarding the possible poisoning of Charles August, and that the von Fersens were responsible.[40]

Murder of Anna Sofia Forssberg

The 1861 murder of 34-year old Anna Sofia Forrsberg was greatly sensationalized at the time, due to no small part of the fact that 21-year old guardsman Per Victor Göthe defiled the woman's body. Forssberg was stabbed to death by Göthe in her store at Hornsgatan, where she also resided, on Easter Day in 1861. Göthe was sentenced to death and executed on 8 February 1862. The execution was witnessed by 4000 onlookers. Göthe was said to have been calm and compliant throughout his execution. Per Victor Göthe was the last convict to be executed below Galgbacken in Hammarbyhöjden.[41]

20th century – present

The 1900s saw the abolition of the death penalty in Sweden. At 8 a.m on 23 November 1910, convicted robber and murderer Alfred Ander was executed by guillotine at Långholmen Prison. This was the last execution to take place in Swedish history, and the first and last time a guillotine was used. The death penalty was officially abolished in 1921 for crime during times of peace. The death penalty for crimes during war-time, however, would not be abolished until 1972. It is worth noting that crime did not increase following the abolition of death penalty.[42]

Three main categories of murder were dominant in Sweden throughout the 20th century. The first category involved unprovoked killings of men by other men, during intoxication. The second category could be called "failed collective suicide" as it involved a mother poisoning her children and then attempting to poison herself, but failing in the latter. The third category is the "crime of passion", where a man kills his wife out of jealousy when she expresses the desire to leave him.[43] The "jealousy" is said to be the uncontrollable feeling that drives the person to commit the murder, and the reason for this uncontrollable feeling is the actions of the victim. The victim is hence blamed by the perpetrator, who often expresses his/her deep love for the victim during interrogations and in court.

The Massacre aboard Prins Carl

The 20th century begins with the deadliest mass murder in Swedish history at the time. The incident didn't occur in Stockholm, but it illustrates how incidents at the time were printed on broadside ballads. The massacre took place on the night of 16 May 1900 aboard the steamer Prins Carl, which was en route to Stockholm from Arboga. 25-year old John Filip Nordlund had recently served his sentence at Långholmen prison. Now a free man, he desired money in order to live a luxurious life, he therefore started plotting a heist to rob and kill all travellers aboard the Prins Carl.

Nordlund's first victim was the ship's captain Olof Rönngren. When Johan Filip stabbed a woman, he was allegedly so forceful that the blade snapped. He escaped in a lifeboat, leaving behind five dead and nine injured. Nordlund was arrested a day later and was sentenced to death. He was executed in Västerås on 10 December 1900 by executioner Gustaf Dalman.[44]

The incident was interpreted in several broadside ballads, such as "Mälaredramat: en sångbar berättelse om de gräsliga ogerningarna å ångbåten Prins Carl"[44] and "En alldeles ny visa om det hemska Mälaredramat".[45]

Alfred Ander

Johan Alfred Ander was the last person to be executed in Sweden and the only Swede to be executed by guillotine,[46] as capital punishment prior to 1907 was executed through manual beheading. On 5 January 1910, Ander robbed Gerells växelkontor, a cash exchange agency at Malmtorgsgatan, near Gustav Adolfs torg. During the robbery, the clerk, Victoria Hellsten, was severely beaten, and she later succumbed to her injuries. Ander managed to steal at least 5 200 crowns in cash, bank notes which would later be used as evidence against him, as some of the notes had been covered in blood. The murder weapon, a steelyard balance was connected to Ander, in addition to a box that Ander had left at Hotel Temperance which contained some of his loot, blood, a photography of Ander as well as his form of identification. On 14 May 1910, Ander was sentenced to death for murder, and he was executed at 8 a.m on 23 November. Ander never admitted to his crimes.[46]

The Von Sydow murders

On 7 March 1932, politician Hjalmar von Sydow is found beaten to death along with two female employees in von Sydow's apartment at 24 Norr Mälarstrand. The bodies had been discovered by the young niece to von Sydow's late wife. The testimony of the niece, who had been living at von Sydow's residence, led police to suspect von Sydow's son and his wife, Fredrik and Ingun von Sydow as the perpetrators. The couple were tracked down and found at a restaurant in Uppsala around 8 p.m. The restaurant staff were instructed to ask Fredrik von Sydow to enter the hallway where police were waiting. As the couple entered the hall, Ingun sat down. Her husband bent down, seemingly in order to kiss her, whereupon Fredrik shot his wife, and subsequently himself. The couple died immediately, and a clear motive for the incident has never been established.[47] The weapon used in the murder of Hjalmar von Sydow, an iron pipe, is today part of an exhibition at the Swedish Police Museum.

Political murders

The late 1900s and the early 2000s are overshadowed by two notorious political assassinations: the 1986 assassination of Olof Palme and the 2003 murder of Anna Lindh.

The assassination of Olof Palme has still not been solved as of 2018, despite it being the subject of one of the most significant criminal investigations in the world. Mijailo Mijailović, Anna Lindh's killer, was, however, arrested two weeks after the murder, and was sentenced to life in prison, due to significant evidence from surveillance cameras and DNA matching.

Terrorist attacks

The 1975 West German Embassy siege occurred on 24 April in Diplomatstaden when members of the far-left militant organization Red Army Faction barricaded themselves inside the embassy and demanded the release of a number of imprisoned RAF members in West Germany. In order to convey the seriousness of their demands, military attaché Andreas von Mirbach and trade official Heinz Hillegaart were both shot and killed. Two of the embassy's occupiers were killed in an explosion at the embassy. The surviving terrorists were arrested when they attempted to flee the embassy and were all sentenced to two consecutive life sentences each.[48] They were eventually pardoned and released between 1994 and 1996.

The 2010 Stockholm bombings took place on 11 December 2010 when two explosions occurred at Olof Palme's street and on Bryggargatan. Thousands of Christmas shoppers were present near the places where the detonations occurred. The explosion at Bryggargatan killed lone terrorist Taimour Abdulwahab, and no other injuries were reported. The incident sparked debate around chemical production regulations[49] as well as the seemingly flawed Swedish system of preventing violent extremism.[50]

At around 3:53 p.m on 7 April 2017, a hijacked lorry was deliberately driven into crowds along Drottninggatan before crashing through a corner of an Åhléns department store, killing five and seriously injuring 14. Rakhmat Akilov, a 39-year old rejected asylum seeker born in the Soviet Union and a citizen of Uzbekistan, was apprehended the same day suspected on probable cause of terrorist crimes through murder. Akilov, who has expressed sympathy with extremist organizations such as ISIL,[51] was sentenced to life in prison and lifetime expulsion from Sweden on 7 June 2018.[52]

References

Notes

- Eisner 2003

- Ericsson 2006, p. 9

- Ericsson 2006, p. 20

- Berg 1972, pp. 6–7

- Ericsson 2006, p. 33

- Ericsson 2006, p. 10

- Andersson 2011

- Ericsson 2006, p. 30

- Ericsson 2006, p. 22

- Berg 1972, p. 1

- Berg 1972, p. 2

- Berg 1972, p. 3

- Berg 1972, pp. 8–9

- Berg 1972, p. 18

- Berg 1972, p. 23

- Berg 1972, p. 24

- Ericson Wolke 2006, pp. 137-143

- Ericsson 2006, p. 38

- Ericsson 2006, p. 62

- Ericsson 2006, p. 69

- Lundevall 2006, p. 51

- Berg 1972, pp. 32–33

- Schéele 2006, pp. 70-71

- "Lars Johansson Lucidor". Svenska familj-journalen: illustrerad månadsskrift, innehållande svensk-historiska samt fosterländska skildringar och berättelser ur naturen och lifvet, original-noveller, skisser och poemer samt uppsatser i vetenskap och konst, m. m (in Swedish). Halmstad: Gernandt. 11: 305. 1872. SELIBR 2809216.

- Ericsson 2006, p. 57

- Ericsson 2006, pp. 58–59

- O'Regan 2004, p. 144

- Hallerdt (1992), p. 17

- O'Regan 2004, p. 147

- O'Regan 2004, p. 159

- Berg 1972, p. 73

- Berg 1972, p. 75

- "Lista över dödsdömda fångar på Smedjegården". www.stockholmskallan.se (in Swedish). Stockholmskällan. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- Guntlack, Jacob, ed. (1770). Den uti Smedjegårds-häktet nu fängslade ryktbare bedragaren och tjufwen Jacob Guntlacks lefwernes-beskrifning, af honom sjelf författad. Stockholm, tryckt uti kongl. tryckeriet, 1770 (in Swedish). Stockholm. SELIBR 2406182.

- Ericsson 2006, p. 93

- Ericsson 2006, pp. 91-92

- Ericsson 2006, p. 94

- Hofer 2011, p. 28

- Sign at the murder scene describing the event.

- Hildebrand, Bengt; Hafström, Gerhard (1956). "Hans Axel Fersen, von". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). 15. National Archives of Sweden. p. 708. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Masoliver 2012, p. 49

- Ericsson 2006, pp. 103–104

- Ericsson 2006, p. 103

- Mälaredramat: en sångbar berättelse om de gräsliga ogerningarna å ångbåten "Prins Carl" [The Mälaren Drama: A sung story about the grisly enormities on the steamer Prins Carl] (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Ol. Hansens förl. 1900. SELIBR 10186398.

- En alldeles ny visa om det hemska "Mälaredramat" som utspelades natten till den 16 maj 1900 af Johan Filip Nordlund [An all new song about the horrible Mälaren Drama which took place the night on 16 May 1900 by John Filip Nordlund] (PDF) (in Swedish). Gothenburg: A. Lindgren & Söner. 1905. SELIBR 10188294.

- Nordlander 2010

- Masoliver 2012, p. 92

- Nordström 2010

- Jönsson 2010a

- Jönsson 2010b

- Johnson, Pollard & Roos 2017

- Jones 2018

Books

- Berg, P. G., ed. (1972). Stockholms blodbestänkta jord (in Swedish). Stockholm: Rediviva. ISBN 91-7120-029-0. SELIBR 7605822.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ericsson, Niklas (2006). Mord i Stockholm. Stockholms historia (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska Media. ISBN 91-85377-10-4. SELIBR 10041382.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ericson Wolke, Lars (2006). Stockholms blodbad (in Swedish). Stockholm: Prisma. ISBN 9151843803. SELIBR 10136327.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garnert, Jan (1998). Stockholmsnatt (in Swedish). Stockholm: Stockholms stadsmuseum. ISBN 91-85239-09-7. SELIBR 7746849.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hasselblad, Björn; Lindström, Frans (1979). Stockholmskvarter: vad kvartersnamnen berättar (in Swedish). Stockholm: AWE/Geber. ISBN 91-20-06252-4. SELIBR 7219146.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hofer, Hanns von (2011). Brott och straff i Sverige: historisk kriminalstatistik 1750-2010 : diagram, tabeller och kommentarer (PDF). Rapport / Kriminologiska institutionen, Stockholms universitet, 1400-853X ; 2011:3 (in Swedish) (4th updated ed.). Stockholm: Kriminologiska institutionen, Stockholms universitet. ISBN 9789197984706. SELIBR 12318083.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lundevall, Peter (2006). Stockholm - den planerade staden (in Swedish). Stockholm: Carlsson. ISBN 9172037881. SELIBR 10166528.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Masoliver, Michael (2012). Stockholm gata för gata: en guide till brotten, böckerna, filmerna, musiken, personerna (in Swedish). Stockholm: Ordalaget. ISBN 9789174690262. SELIBR 12342708.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Regan, Christopher (2004). Gustaf III:s Stockholm: glimtar ur 1700-talets stadsliv (in Swedish). Stockholm: Forum. ISBN 9137125974. SELIBR 9472226.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Andersson, Axel (18 February 2011). "Mord som skakat Sverige". Populär Historia (in Swedish) (2). Retrieved 14 October 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eisner, Manuel (2003). "Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime" (PDF). Crime and Justice. 30: 83–142. doi:10.1086/652229.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schéele, Maria von (2006). "Mäster Mikael" (PDF). Blick (Stockholm) (in Swedish). 3. ISSN 1652-8328. SELIBR 10674939.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Web

- Jones, Evelyn (7 June 2018). "Stockholm terrorist Rakhmat Akilov sentenced to life in prison". Dagens Nyheter. Retrieved 7 June 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Simon; Pollard, Niklas; Roos, Rebecka (10 April 2017). "Uzbek suspect in Swedish attack sympathized with Islamic State". Stockholm. Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jönsson, Olof (17 December 2010a). "EU saknar regelverk för bombingredienser". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-05-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jönsson, Olof (16 December 2010b). "Ont om förebilder för avhoppande islamister". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-05-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nordlander, Jenny (23 November 2010). "Ander blev den siste att avrättas". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 29 May 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nordström, Johan (1 October 2010). "Terrordåd som skakat Sverige". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 2018-05-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)