Himyarite Kingdom

The Himyarite Kingdom (Arabic: مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, Hebrew: ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar (Arabic: حِمْيَر, Ḥimyar, Sabaean: 𐩢𐩣𐩺𐩧𐩣) (fl. 110 BCE–520s CE), historically referred to as the Homerite Kingdom by the Greeks and the Romans (its subjects being called Homeritae), was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According to classical sources, their capital was the ancient city of Zafar, relatively near the modern-day city of Sana'a.[1] Himyarite power eventually shifted to Sana’a as the population increased in the fifth century.

Himyar 𐩢𐩣𐩺𐩧𐩣 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110 BCE–525 CE | |||||||||

| Capital | Zafar Sana'a (from the beginning of the 4th century)[1] | ||||||||

| Common languages | Ḥimyarite | ||||||||

| Religion | Paganism Judaism after 390 CE | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 275–300 CE | Shammar Yahri'sh | ||||||||

• 390–420 CE | Abu Karib As'ad | ||||||||

• 510s–525 CE | Yusuf Ash'ar Dhu Nuwas | ||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||

• Established | 110 BCE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 525 CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Yemen |

|

| Timeline |

After the establishment of their kingdom, it was ruled by kings from dhū-Raydān tribe. The kingdom was named Raydān.[2]

The kingdom conquered neighbouring Saba' in c. 25 BCE (for the first time), Qataban in c. 200 CE, and Haḍramaut c. 300 CE. Its political fortunes relative to Saba' changed frequently until it finally conquered the Sabaean Kingdom around 280.[3] Himyar then endured until it finally fell to invaders from the Kingdom of Aksum in 525 CE.[4]

The Himyarites originally worshiped most of the South-Arabian pantheon, including Wadd, ʿAthtar, 'Amm and Almaqah. Since at least the reign of Abikarib Asʿad (c. 384 to 433 CE), Judaism was adopted as the de-facto state religion. The religion may have been adopted to some extent as much as two centuries earlier, but inscriptions to polytheistic deities ceased after this date. It was embraced initially by the upper classes, and possibly a large proportion of the general population over time.[2]

History

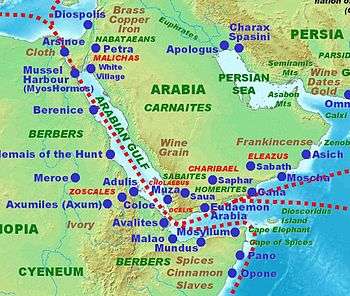

The Ḥimyarite Kingdom maintained nominal control in Arabia until 525. Its economy was based on agriculture, and foreign trade centered on the export of frankincense and myrrh. For many years, the kingdom was also the major intermediary linking East Africa and the Mediterranean world. This trade largely consisted of exporting ivory from Africa to be sold in the Roman Empire. Ships from Ḥimyar regularly travelled the East African coast, and the state also exerted a large amount of Influence both cultural, religious and political over the trading cities of East Africa whilst the cities of East Africa remained independent. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes the trading empire of Himyar and its ruler "Charibael" (probably Karab'il Watar Yuhan'em II), who is said to have been on friendly terms with Rome:

"23. And after nine days more there is Saphar, the metropolis, in which lives Charibael, lawful king of two tribes, the Homerites and those living next to them, called the Sabaites; through continual embassies and gifts, he is a friend of the Emperors."

Early period (115 BC until 300 AD)

During this period, the Kingdom of Ḥimyar conquered the kingdoms of Saba' and Qataban and took Raydan/Zafar for its capital instead of Ma'rib; therefore, they have been called Dhu Raydan (Arabic: ذو ريدان). In the early 2nd century AD Saba' and Qataban split from the Kingdom of Ḥimyar; yet in a few decades Qataban was conquered by Hadhramaut (conquered in its turn by Ḥimyar in the 4th century), whereas Saba' was finally conquered by Ḥimyar in the late 3rd century.[6]

Ẓafār's ruins cover scattered over 120 hectare on Mudawwar Mountain 10 km north-north-west of the town of Yarim.[7] Early, Empire and Late/Post art periods have been identified.[8]

Ẓafār was first agriculturally self-sufficient. The 6th century reveals a drastic loss of towns and population. Until the early 3rd century, trade flourished. Later it failed perhaps because of the Nabataean domain over the north of Ḥijāz and because of intertribal warfare. Families of Qaḥṭān were disunited and scattered over Arabia, particularly to the east.

Jewish monarchy

The Himyarite kings appear to have abandoned polytheism and converted to Judaism around the year 380, several decades after the conversion of the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum to Christianity (328). No changes occurred in the people's script, calendar, or language (unlike at Aksum after its conversion).[9] This date marks the end of an era in which numerous inscriptions record the names and deeds of kings, and dedicate buildings to local (e.g. Wagal and Simyada) and major (e.g. Almaqah) gods. From the 380s, temples were abandoned and dedications to the old gods ceased, replaced by references to Rahmanan, "the Lord of Heaven" or "Lord of Heaven and Earth".[10] The political context for this conversion may have been Arabia's interest in maintaining neutrality and good trade relations with the competing empires of Byzantium, which first adopted Christianity under Constantine the Great and the Sasanian Empire, which alternated between Zurvanism and Manichaeism.[11]

One of the first Jewish kings, Tub'a Abu Kariba As'ad (r. 390–420), is believed to have converted following a military expedition into northern Arabia in an effort to eliminate Byzantine influence. The Byzantine emperors had long eyed the Arabian Peninsula and sought to control the lucrative spice trade and route to India. The Byzantines hoped to establish a protectorate by converting the inhabitants to Christianity. Some progress had been made in northern Arabia but they had little success in Ḥimyar.[11]

Abu-Kariba's forces reached Yathrib and, meeting no resistance, they passed through the city, leaving the king's son behind as governor. Abu-Kariba soon received news that the people of Yathrib had killed his son. He turned back in order to wreak vengeance on the city. After cutting down the palm trees from which the inhabitants derived their main income, he laid siege to the city. The Jews of Yathrib fought side by side with their pagan neighbors.

During the siege Abu-Kariba fell severely ill. Two Jewish scholars in Yathrib, Ka'ab and Asad by name, called on the king in his camp and used their knowledge of medicine to restore him to health. While attending the king, they pleaded with him to lift the siege and make peace. The sages' appeal is said to have persuaded Abu-Kariba; he called off his attack and also embraced Judaism along with his entire army. At his insistence, the two Jewish scholars accompanied the Ḥimyarite king back to his capital, where he demanded that all his people convert to Judaism. Initially, there was great resistance. After an ordeal had justified the king's demand and confirmed the truth of the Jewish faith, many Himyarites supported Judaism. Some historians argue that the people were not motivated by politics, but that Judaism, by its philosophical, simplistic, and austere nature, was attractive to the nature of the Semitic people.[12]

Abu-Kariba continued to engage in military campaigns and met his death under unclear circumstances. Some scholars believe that his own soldiers killed him. He left three sons, Ḥasan, 'Amru, and Zorah, all of whom were minors at the time. After Abu-Kariba's demise, a pagan named Dhū-Shanatir seized the throne.[11] In the reign of Subahbi'il Yakkaf, Azqir, the son of Abu Karib Assad and serving as a Christian missionary from Najrān, was put to death after he had erected a chapel with a cross. Christian sources interpret the event as a martyrdom at Jewish hands: the site for his execution, Najrān, was said to have been chosen on the advice of a rabbi,[13] but indigenous sources do not mention persecutions on the grounds of faith. His death may have been intended to deter the extension of Byzantine influence.[14]

The first Aksumite invasion took place sometime in the 5th century and was triggered by the persecution of Christians. Two Christian sources, including the Zuqnin Chronicle once attributed to Dionysius I Telmaharoyo, which was written more than three centuries later, say that the Himyarite king prompted the killings by stating, "This is because in the countries of the Romans the Christians wickedly harass the Jews who live in their countries and kill many of them. Therefore I am putting these men to death."[15] In retaliation the Aksumites invaded the land and thereafter established a bishopric and built Christian churches in Zafar.

The Jewish monarchy in Ḥimyar ended with the reign of Yṳsuf, known as Dhū Nuwās, who, in 523, persecuted the Himyarite Christian population of Najrān.[16][17] By the year 500, on the eve of the regency of Marthad'īlān Yanūf (c. 500-515) the kingdom of Himyar exercised control over much of the Arabian peninsula.[18] It was during his reign that the Himyarite kingdom began to become a tributary state of Aksum, the process concluding by the time of the reign of Ma'dīkarib Yafur (519–522), a Christian appointed by the Aksumites.

A coup d'état ensued, with Dhu Nuwas, who had attempted to overthrow the dynasty several years earlier, assuming authority after killing the Aksumite garrison in Zafār. He proceeded to engage the Ethiopian guards, and their Christian allies in the Tihāma coastal lowlands facing Abyssinia. After taking the port of Mukhawān, where he burnt down the local church, he advanced south as far as the fortress of Maddabān overlooking the Bab-el-Mandeb, where he expected Kaleb Ella Aṣbeḥa to land his fleet.[10] The campaign eventually killed between 11,500 and 14,000, and took a similar number of prisoners.[18] Mukhawān became his base, while he dispatched one of his generals, a Jewish prince named Sharaḥ'īl Yaqbul dhu Yaz'an, against Najrān, a predominantly Christian oasis, with a good number of Jews, who had supported with troops his earlier rebellion, but refused to recognize his authority after the massacre of the Aksumite garrison. The general blocked the caravan route connecting Najrān with Eastern Arabia.[10]

Religious culture

During this period, references to pagan gods disappeared from royal inscriptions and texts on public buildings, and were replaced by references to a single deity. Inscriptions in the Sabean language, and sometimes Hebrew, called this deity Rahman (the Merciful), “Lord of the Heavens and Earth,” the “God of Israel” and “Lord of the Jews.” Prayers invoking Rahman's blessings on the “people of Israel” often ended with the Hebrew words shalom and amen. [19]

There is evidence that the solar goddess Shams was especially favoured in Himyar, being the national goddess and possibly an ancestral deity.[20][21][22][23]

Ancestral divisions of Himyar

- Himyar: The most famous of whose septs were Zaid Al-Jamhur, Banu Quda'a and Sakasik.

- Kahlan: The most famous of whose septs were Hamdan, Azd, Anmar, Ṭayy (today their descendants are known as Shammar), Midhhij, Kindah, Lakhm, Judham

Kahlan septs emigrated from Yemen to dwell in the different parts of the Arabian Peninsula prior to the Great Flood (Sail Al-‘Arim of Ma’rib Dam), due to the failure of trade under the Roman pressure and domain on both sea and land trade routes following Roman occupation of Egypt and Syria.

Naturally enough, the competition between Kahlan and Ḥimyar led to the evacuation of the first and the settlement of the second in Yemen.

The emigrating septs of Kahlan can be divided into four groups:

- Azd: Who, under the leadership of ‘Imrān bin ‘Amr Muzaiqbā’, wandered in Yemen, sent pioneers and finally headed northwards. Details of their emigration can be summed up as follows:

- Tha‘labah bin ‘Amr left his tribe Al-Azd for Ḥijāz and dwelt between Tha‘labiyah and Dhī Qār. When he gained strength, he headed for Madīnah where he stayed. Of his seed are Aws and Khazraj, sons of Haritha bin Tha‘labah.

- Haritha bin ‘Amr, known as Khuzā‘ah, wandered with his people in Hijaz until they came to Mar Az-Zahran. They conquered the Ḥaram, and settled in Makkah after having driven away its people, the tribe of Jurhum.

- ‘Imrān bin ‘Amr and his folks went to ‘Oman where they established the tribe of Azd whose children inhabited Tihama and were known as Azd-of-Shanu’a.

- Jafna bin ‘Amr and his family, headed for Syria where he settled and initiated the kingdom of Ghassan who was so named after a spring of water, in Ḥijāz, where they stopped on their way to Syria.

- Lakhm and Judham: Of whom was Nasr bin Rabi‘a, father of Manadhira, Kings of Heerah.

- Banū Ṭayy: Who also emigrated northwards to settle by the so- called Aja and Salma Mountains which were consequently named as Tai’ Mountains. The tribe later became the tribe of Shammar.

- Kindah: Who dwelt in Bahrain but were expelled to Hadramout and Najd where they instituted a powerful government but not for long, for the whole tribe soon faded away.

Another tribe of Himyar, known as Banū Quḑā'ah, also left Yemen and dwelt in Samāwah on the borders of Iraq.

However, it is estimated that the majority of the Ḥimyar Christian royalty migrated into Jordan, Al-Karak, where initially they were known as Banū Ḥimyar (Sons of Ḥimyar). Many later on moved to central Jordan to settle in Madaba under the family name of Al-Hamarneh (pop 12,000, est. 2010)

Language

It is a matter of debate whether the Ṣayhadic Himyarite language was spoken in the south-western Arabian peninsula until the 10th century.[24] The few 'Himyarite' texts seem to be rhymed.

Dynasties and rulers after the spread of Islam

After the spread of Islam in Yemen, Himyarite noble families were able to re-establish control over parts of Yemen.

- Yufirid Dynasty over most of Yemen (847–997)

- Mahdid Dynasty over Southern Tihama (1159–1174)

- Manakhis over Taiz (ninth century)

See also

- Ancient history of Yemen

- Rulers of Sheba and Himyar

- Tub'a Abu Kariba As'ad

- Yemenite Jews

- Zafar, Yemen

- Ethiopian–Persian wars

- List of Jewish states and dynasties

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Himyar

- Jérémie Schiettecatte. Himyar. Roger S. Bagnall; Kai Brodersen; Craige B. Champion; Andrew Erskine; Sabine R. Huebner. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, John Wiley & Sons, 2017, 9781444338386.ff10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah30219ff. ffhalshs-01585072ff

- See, e.g., Bafaqih 1990.

- Playfair, Col (1867). "On the Himyaritic Inscriptions Lately brought to England from Southern Arabia". Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London. 5: 174–177. doi:10.2307/3014224. JSTOR 3014224.

- Source

- Korotayev A. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996.

- Paul A.Yule, Late Antique Arabia Ẓafār, Capital of Ḥimyar, Rehabilitation of a ‘Decadent’ Society, Excavations of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1998–2010 in the Highlands of the Yemen, Abhandlungen Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, vol. 29, Wiesbaden 2013, ISSN 0417-2442, ISBN 978-3-447-06935-9

- Paul Yule, Himyar–Die Spätantike im Jemen/Late Antique Yemen, Aichwald 2007, pages 123-160ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6; R. Stupperich and [[P. Yule, Ḥimyarite Period Bronze Sculptural Groups from the Yemenite Highlands, in: A. Sedov (ed.), Arabian and Islamic Studies A Collection of Papers in Honour of Mikhail Borishovic Piotrovskij on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday, Moscow, 2014, 338–67. ISBN 978-5-903417-63-6

- Christian Julien Robin, "Arabia and Ethiopia," in Scott Johnson (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, Oxford University Press 2012 pp.247-333, p.279.

- Norbert Nebes, 'The Martyrs of Najrān and End of the Ḥimyar: On the Political History of South Arabia in the Early Sixth Century,' the Angelika Neuwirth, Nicolai Sinai, Michael Marx (eds.), The Qur'ān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations Into the Qur'ānic Milieu, BRILL 2010 pp.27-60, p.43.

- "The Jewish Kingdom of Himyar (Yemen): Its Rise and Fall," by Jacob Adler, Midstream, May/June 2000, Volume XXXXVI No. 4

- P. Yule, Himyar Spätantike im Jemen, Late Antique Yemen, Aichwald, 2007, p. 98-99

- Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People, Verso 2009 p.194.

- Robert Hoyland,Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge, 2001, p.51.

- Christopher Haas, 'Geopolitics and Georgian Identity in Late Antiquity: The Dangerous World of Vakhtang Gorgasali,' in Tamar Nutsubidze, Cornelia B. Horn, Basil Lourié(eds.),Georgian Christian Thought and Its Cultural Context, BRILL pp.29-44, p.39.

- G.W. Bowersock, The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Kingdom in Arabia, Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, 2011, ; The Adulis Throne, Oxford University Press, in press.

- Bantu, Vince L. (10 March 2020). A Multitude of All Peoples: Engaging Ancient Christianity's Global Identity. InterVarsity Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8308-2810-4.

- Christian Julien Robin,'Arabia and Ethiopia,'in Scott Johnson (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity, Oxford University Press, 2012, pp.247-333.p.282

- David, Ariel (15 March 2016). "Before Islam: When Saudi Arabia Was a Jewish Kingdom". Haaretz.

- J. F. Breton (Trans. Albert LaFarge), Arabia Felix From The Time Of The Queen Of Sheba, Eighth Century B.C. To First Century A.D., 1998, University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame (IN), pp. 119-120.

- Julian Baldick (1998). Black God. Syracuse University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8156-0522-5.

- Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, 1999 - 1181 páginas

- J. Ryckmans, "South Arabia, Religion Of", in D. N. Freedman (Editor-in-Chief), The Anchor Bible Dictionary, 1992, Volume 6, op. cit., p. 172

- Pro: C. Robin, Himyaritic, in Encycl. Arab. Language & Linguistics, 2010, 256-261, ISBN 978-90-04-14973-1; Contra: P. Stein, The ‘Himyaritic’ Language in pre-Islamic Yemen A Critical Re-evaluation, Semitica et classica 1, 2008, 203–212, ISSN 2295-8991

Bibliography

- Alessandro de Maigret. Arabia Felix, translated Rebecca Thompson. London: Stacey International, 2002. ISBN 978-1-900988-07-0

- Andrey Korotayev. Ancient Yemen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-19-922237-7.

- Andrey Korotayev. Pre-Islamic Yemen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1996. ISBN 978-3-447-03679-5.

- Bafaqīh, M. ‛A., L'unification du Yémen antique. La lutte entre Saba’, Himyar et le Hadramawt de Ier au IIIème siècle de l'ère chrétienne. Paris, 1990 (Bibliothèque de Raydan, 1).

- Paul Yule, Himyar Late Antique Yemen/Die Spätantike im Jemen, Aichwald, 2007, ISBN 978-3-929290-35-6

- Paul Yule, Zafar-The Capital of the Ancient Himyarite Empire Rediscovered, Jemen-Report 36, 2005, 22-29

- Paul Yule, (ed.), Late Antique Arabia Ẓafār, Capital of Ḥimyar, Rehabilitation of a 'Decadent' Society, Excavations of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg 1998–2010 in the Highlands of the Yemen, Abhandlungen Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, vol. 29, Wiesbaden 2013, ISSN 0417-2442, ISBN 978-3-447-06935-9

- Joseph Adler, "The Jewish Kingdom of Himyar (Yemen): Its Rise and Fall" Midstream, May/June 2000, Volume XXXXVI, No. 4

- R. Stupperich–P. Yule, Ḥimyarite Period Bronze Sculptural Groups from the Yemenite Highlands, in: A. Sedov (ed.), Arabian and Islamic Studies A Collection of Papers in Honour of Mikhail Borishovic Piotrovskij on the Occasion of his 70th Birthday, Moscow, 2014, 338–67. ISBN 978-5-903417-63-6

External links

- friesian.com, Islam by Kelley L. Ross, Ph.D.

- archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de

- heidicon.ub.uni-heidelberg.de