Heliothis punctifera

Heliothis punctifera (Walker, 1857) or the lesser budworm, is an Australian moth of the family Noctuidae; one of the most migratory families of insects.[1] It is considered a pest species to agricultural crops, however, due to its inland habitat, is found to be less damaging to agricultural areas than other species of the genus.[2][3]

| Heliothis punctifera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. punctifera |

| Binomial name | |

| Heliothis punctifera Walker, 1857 | |

| |

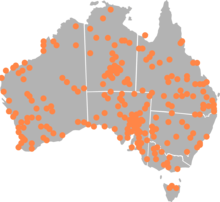

| Distribution of Heliothis punctifera | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

Francis Walker first described Heliothis punctifera in 1857. The lesser budworm is an Australian species of the genus Heliothis from the family Noctuidae.[3][4]

Heliothine moths are considered pests, however not all species are. The lesser budworm can be confused with the native budworm (Helicoverpa punctigera) and the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera), Australia's top two pest species, who are both more prevalent in agricultural areas and considered more detrimental to crops than the lesser budworm.[2][5]

Description

The lesser budworm caterpillar has stripes of dark green to light brown that run the length of its body and are separated by thin white lines. There is a thick pale stripe on each side of its body. The light coloured hairs behind its head are what distinguish it most from other similar species.[6]

The adult lesser budworm has a bold defined pattern on its brown to orange forewings. Its hindwings are dark and fade to the base which is a lighter colour.[6] The underside of each forewing has a large dark comma-shape. In moth form it has a wingspan is about 30 mm.[7]

Similar species

The lesser budworm looks very similar to the native budworm and the cotton bollworm, particularly in the larval stage where the species are difficult to differentiate.[1][8]

The following can be used to identify differences between H. punctifera and the other similar species:[8]

Larval stage:

Helicoverpa punctigera – (differences: ranges in colour from light brown, to green, to black and has black hairs around the collar).

Helicoverpa armigera – (differences: black/brown hair on body).

Moth stage:

Helicoverpa punctigera – (differences: lighter and slightly reddish in comparison with a less distinctive wing pattern).

Helicoverpa armigera – (differences: forewing has distinctive kidney-shaped marking in the centre, hind-wing has dark bands and a lighter patch in the centre).

.jpg)

Distribution

It is found primarily in arid inland desert regions, however, it is not restricted to this environment and is found across all states of Australia.[8][9]

Characteristics and migration

Noctuid moths tend to travel at night at high altitudes, capable of flying hundreds of kilometres. Because the lesser budworm occurs in arid inland areas, generally far from agricultural areas, there is little monitoring data on their migrations compared to the more popular pest species of heliothine moth.[3]

Lesser budworm caterpillars are considered extremely mobile, moving across the desert sands between host plants in their quest to consume many flower heads to guarantee their development. The desert plants that comprise most of their diet bloom in the winter months in a seasonal event after rains in the inland regions.[10]

Reproduction and lifecycle

The adult life of a heliothine moth is about 10 days.[11] In this time, the female moth can lay substantial amount of eggs in host plants; up to 1000.[12][11]

Successful breeding of the lesser budworm and other heliothine moths, depends on significant rainfall in late autumn and early winter which encourages the growth of desert flowers. The variability of rainfall across arid inland Australia ensures some growth of host plants is interspersed across the country, however the amounts and locations are variable.[3]

The eggs of heliothine moths tend to hatch within 3–10 days, dependent on how warm the temperature is. Eggs and pupae have the capacity to enter a diapause phase of overwintering if temperatures are too low for metamorphosis.[13]

By late winter and early spring, incoming warmer and drier weather usually signals the senescence of the seasons individuals and brings an influx of the lesser budworm in its moth stage. Favourable wind patterns and warm nights extend their migration.[3]

Diet

The Asteraceae are their desert flowers of choice, which tend to bloom in the winter months in large groups. Lesser budworms have been observed feeding predominantly on the species of annual yellow top, Senecio gregorii (F. Muell) and the poached egg daisy, Polycalymma stuartii (F. Muell & Sond.) and appear to prefer the annual yellow top.[2]

A study on the host location behaviour of the lesser budworm found that the distribution of caterpillars on plants is not just dependent on the adults choice for the oviposition of larvae. The caterpillars were observed moving between plants. They were also seen feeding on both the flowering heads and the vegetative tissue of the plants. The study suggests that the purpose of including the vegetative tissue in their diet is to cope with host plant overcrowding. The end of the blooming season exhibits more movement as competition for host plants is highest.[2]

Agricultural impacts

Heliothine moths are considered particularly devastating pests to agricultural areas. Due to their polyphagous eating habits, they can move between crop species and as their numbers intensify, can have huge impacts. The most damaging species identified is the cotton bollworm.[5]

The lesser budworm can be damaging to crops, however, because they primarily occur in outback areas of Australia, they are only sometimes found in agricultural areas. The ideal conditions required for the lesser budworm to cause significant damage to crops are substantial rains in summer that encourage growth in vegetation, teamed with significant winds that permit flight over long distances to reach agricultural areas. The last reported large-scale occurrence of lesser budworm damage to crops was in 2005.[1]

There are reports of damage to wheat crops in Deniliquin where white heads appeared similar to crown rot. The larvae seemed to have chewed through plants to eat the inside of the stems which affects nutrient flow to the heads of the wheat plants.[1]

The moths can occur in huge numbers when migrating within the country. In November 2005, this species caused a panic at Murray Downs Golf Club near Swan Hill, when swarms of them invaded the course and clubhouse. The walls, ceiling and floor of the clubhouse were covered with resting moths.[7] It is considered a pest on alfalfa, Mexican cotton and wheat.

References

- "Lesser budworm". www.cesaraustralia.com. PestFacts. November 26, 2010. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- Cunningham, J.P.; Lange, C.L.; Walter, G.H.; Zalucki, M.P. (2011). "Host location behaviour in the desert caterpillar, Heliothis punctifera". Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 141: 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2011.01163.x.

- Gregg, P.C.; del Socorro, A.P.; Rochester, W.A. (2001). "Field test of a model of migration of moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in inland Australia". Australian Journal of Entomology. 40 (3): 249–256. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6055.2001.00228.x.

- IFB Common (1953). "The Australian species of Heliothis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and their pest status". The Australian Journal of Zoology. 1 (3) – via ResearchGate.

- Cunningham, J.P.; Zalucki, M.P. (2014). "Understanding Heliothine (Lepidoptera: Heliothinae) Pests: What is a Host Plant?". Journal of Economic Entomology. 107 (3): 881–896. doi:10.1603/EC14036.

- Herbison-Evans, D.; Crossley, S. (2013). "Heliothis punctifera". Coffs Harbour Butterfly House.

- Don Herbison-Evans & Stella Crossley (July 23, 2008). "Heliothis punctifera". uts.edu.au. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- "Lesser budworm and identification". cesaraustralia.com. PestFacts. September 21, 2007. Retrieved 2018-06-06.

- "Budworm trapping". pir.sa.gov.au. PestFacts. 2016. Retrieved 2018-06-10 – via Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA.

- Zalucki, M.P.; Murray, D.A.H.; Gregg, P.C.; Fitt, G.P.; Twine, P.H.; Jones, C. (1994). "Ecology of Helicoverpa-Armigera (Hubner) and Heliothis-Punctigera (Wallengren) in the Inland of Australia - Larval Sampling and Host-Plant Relationships During Winter and Spring". Australian Journal of Zoology. 42 (3): 329–346. doi:10.1071/ZO9940329.

- "Insects: Understanding Helicoverpa ecology and biology in southern Queensland: Know the enemy to manage it better" (PDF). Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Queensland Government. 2005. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- Miles, M.; McDonald, D. (2012). "Insect pests. In P.A. Salisbury, T.D. Potter, G. McDonald, & A.G. Green (Eds.), Canola in Australia: The first thirty years. Paper presented at the 10th International Rapeseed Congress, Canberra, Australia".

- Cullen, J.M.; Browning, T.O. (1978). "The influence of photoperiod and temperature on the induction of diapause in pupae of Heliothis punctigera". Journal of Insect Physiology. 24 (8–9): 595–601. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(78)90122-1.