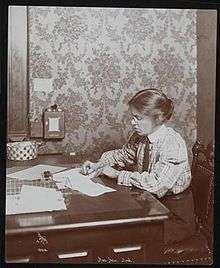

Helen Marot

Helen Marot (June 9, 1865 – June 3, 1940) was an American writer, librarian, and labor organizer. She is best remembered for her efforts to address child labor and improve the working conditions of women. She was from Philadelphia and became active in investigating working conditions among children and women. As a librarian, she worked at several important institutions and helped organize the Free Library of Economics and Political Science in 1897. Marot was a member of the Women's Trade Union League. She later organized the Bookkeepers, Stenographers and Accountants Union in New York. In 1912, she was part of a commission that investigated the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. She was an active writer and her articles about the labor movement appeared in many periodicals of the day.

Early life

Marot was born on June 9, 1865 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She grew up in an affluent family and received a Quaker education. From 1895 to 1896, Marot was the literary editor of Ladies' Home Journal where she was responsible for answering literary queries to the magazine. During this time, she compiled a 288-page reader's guide containing over 5,000 books. Included were some 170 author summaries.[1]

Early library work

Marot left Ladies' Home Journal in April 1896 to organize the King Library of the Church of the Redeemer in Andalusia, Pennsylvania. In September 1896 she worked as a librarian in Wilmington, Delaware as a cataloger. She stayed at the library for three years. The head librarian at the time, Enos L. Doan, remarked on her work: "She brought to it taste and literary discrimination of a high order—qualities which, in addition to her thorough technical training, gave her unusual efficiency in the performance of her duties."[1]

The Free Library of Economics and Political Science

In 1897 Marot, along with Dr. George M. Gould and Innes Forbes, opened a private library specializing in works on social and economic topics. The Free Library of Economics and Political Science concentrated on issues relating to social and economic reform and was greatly influenced by The Fabian Society, a socialist organization. It was located on the second floor of a department store on Filbert Street in Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Record described the library in its pages on June 15, 1897:

Philadelphia has been enriched with a library distinctively modern and progressive in spirit... The new library forms an important supplement to the municipal system, since the topics of the day and the problems of the industrial and sociological world cannot be thoroughly followed by an institution for the general circulation of books. With its proposed technical classification of magazine literature and an accessible collection of pamphlets and volumes, the Library of Economics should become a powerful factor for civic and social education in the community and Commonwealth.[2]

Marot explained the importance of the library in 1902: "It was founded on the idea that freely offered opportunities from education in economics and political science make directly for a more intelligent public opinion and a higher citizenship."[2]

The collection included foreign and domestic literature. It consisted of six hundred books, over two thousand pamphlets, and ninety-one periodicals. This literature, more particularly the periodicals, was not found elsewhere and thus met a most specific community need. The entire collection was donated by individuals and various organizations such as American Academy of Political and Social Science, Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Church Social Union, Civic Club of Philadelphia, Direct Legislation League, Englishwoman's Review, Fabian Society, Humboldt Publishing Company, Independent Labour Party, Indian Rights Association, Labor Exchange, and Land Nationalization League, among others.

To keep up to date with current information, the library collected news clippings and government publications, reports of labor societies, and other similar works. Indeed, a considerable part of the collection consisted of government, state, and municipal reports received from the United States government, the different states, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and New South Wales. Although the collection was small, teachers, students, and library patrons found its classified and indexed pamphlets and magazine literature concerning present-day problems to be satisfactory.

In addition, the patrons could purchase books and were permitted to check out books when they were unable to come to the reading room during library hours. The library was open daily from 11 a.m. until 6 p.m. and on Sunday, until 10 p.m. The small library soon became "the center of liberal thought in Philadelphia"—a popular gathering place for Philadelphian reformers and socialists. In addition to the usual work of a special library, public and private lectures and classes were given to different associations. Besides being the chairwoman of the library committee, Marot was also on the lectures committee, which were all well attended, the rooms being, in fact, more than filled.

The first lecture addressed the topic of "The Economics of Socialism." It was given free on October 30, 1897 by James R. MacDonald of the London Fabian Society and future Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. At the second meeting, on February 8, 1898, Professor Joseph French Johnson, Dr. Henry Rogers Seager, Charles Richardson, and Professor William I. Hull discussed and lectured on "Education in Economics." On March 19, 1898 a lecture on "Economic Education, the Salvation of Society" was given by Dr. Daniel G. Brinton.

Through her library, Helen Marot participated in educating Philadelphians to social changes and pursued the socialist cause for building a more just and humane society with perseverance, courage, and a combination of hardheaded realism and guileless romanticism.[2]

Labor and publishing work

In 1899 she published A Handbook of Labor Literature and also conducted and investigation for the U.S. Industrial Commission into working conditions in the custom tailoring trades in Philadelphia. In 1902 Marot investigated child labor in New York City for the Association of Neighborhood Workers and helped form the New York Child Labor Committee. With Florence Kelley and Josephine Clara Goldmark she drew up a report on child labor in the city that influential in the passage of the 1903 Compulsory Education Act by the state legislature.[1]

In 1906 Marot became executive secretary of the New York branch of the national Women's Trade Union League. Marot also was responsible for creating the Bookkeepers, Stenographers and Accountants Union of New York. She was the organizer and leader of the first great strike of shirtwaist makers and dressmakers (1909–10) under the banner of the new International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union.

In 1913, Marot resigned from her work with the trade union league. In 1914, she published American Labor Unions (1914), a work on the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World. She then served on the editorial board of The Masses (1916–17), a radical journal. After, she then served on the staff of The Dial (1918–20). She was also a member of the U.S. Industrial Relations Commission (1914–16).[1]

Helen Marot lived with her life partner, progressive educational reformer Caroline Pratt, until her death in on June 3, 1940, in New York, New York.

See also

References

- Nutter, K. (2010). Helen Marot. American National Biography. Available from: Gale Virtual Reference Library, Ipswich, MA.

- Gaudioso, M. (1992). Helen Marot: Librarian, 1865-1901. (Order No. 1350082, San Jose State University). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Further reading

- Faderman, Lillian. (1999.) To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America--a History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

- Marot, H. (1899.) A handbook of labor literature: Being a classified and annotated list of the more important books and pamphlets in the English language. Philadelphia Free Library of Economics and Political Science: PA. Digitized by University of Michigan Library.

- Marot, H. (1914.) American labor unions. Henry Holt: NY. Digitized.

- Marot, H. (1918.) Creative impulse in industry: A proposition for educators. E.P. Dutton: NY. Digitized.