Hectocotylus

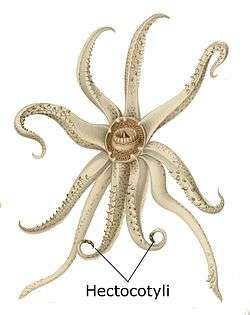

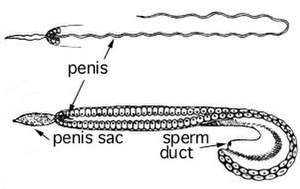

A hectocotylus (plural: hectocotyli) is one of the arms of male cephalopods that is specialized to store and transfer spermatophores to the female.[1] Structurally, hectocotyli are muscular hydrostats. Depending on the species, the male may use it merely as a conduit to the female, or he may wrench it off and present it to the female.

The hectocotyl arm was first described in Aristotle's biological works. Although Aristotle knew of its use in mating, he was doubtful that a tentacle could deliver sperm. The name hectocotylus was devised by Georges Cuvier, who first found one embedded in the mantle of a female argonaut. Supposing it to be a parasitic worm, in 1829 Cuvier gave it a generic name.[2][3][4][5]

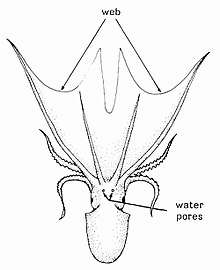

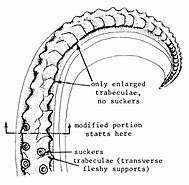

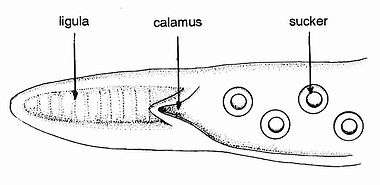

Anatomy

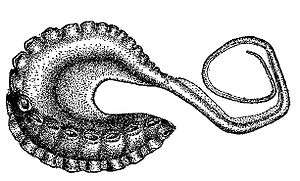

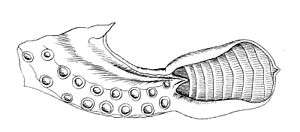

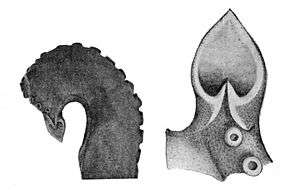

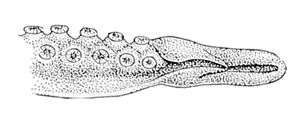

Generalized anatomy of squid and octopod hectocotyli:

Variability

Hectocotyli are shaped in many distinctive ways, and vary considerably between species. The shape of the tip of the hectocotylus has been much used in octopus systematics.

- Many coleoids lack hectocotyli altogether.[6]

- Among Decapodiformes (ten-limbed cephalopods), generally either one or both of arms IV are hectocotylized.

- In incirrate octopuses it is one of arm pair III.[6] Rare examples of double and bilateral hectocotylization have also been recorded in incirrate octopuses.[7][8]

- In male Seven-arm Octopuses (Haliphron atlanticus), the hectocotylus develops in an inconspicuous sac in front of the right eye that gives the male the appearance of having only seven arms.

- In argonauts, the male transfers the spermatophores to the female by putting its hectocotylus into a cavity in the mantle of the female, called the pallial cavity. This is the only contact the male and female have with each other during copulation, and it can be at a distance. During copulation, the hectocotylus breaks off from the male. The funnel–mantle locking apparatus on the hectocotylus keeps it lodged in the pallial cavity of the female.

| Shape of hectocotylus | Species | Family |

|---|---|---|

|

Abraliopsis morisi | Enoploteuthidae |

|

Argonauta bottgeri | Argonautidae |

|

Bathypolypus arcticus | Octopodidae |

|

Graneledone verrucosa | Octopodidae |

|

Haliphron atlanticus | Alloposidae |

|

Ocythoe tuberculata | Ocythoidae |

|

Scaeurgus patagiatus | Octopodidae |

|

Tremoctopus violaceus | Tremoctopodidae |

|

Uroteuthis duvauceli | Loliginidae |

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hectocotylus. |

- Roger T. Hanlon; John B. Messenger (22 March 2018). Cephalopod Behaviour. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-54674-4.

- Leroi, Armand Marie. The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1913). On Aristotle as a biologist, with a prooemion on Herbert Spencer. Being the Herbert Spencer Lecture before the University of Oxford, on February 14, 1913. Oxford University Press. p. 19.

- Nixon M.; Young J.Z. (2003). The brains and lives of Cephalopods. Oxford University Press.

- "GBIF:Hectocotylus Cuvier, 1829". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Young, R.E., M. Vecchione & K.M. Mangold (1999). Cephalopoda Glossary. Tree of Life Web Project.

- Robson, G.C. 1929. On a case of bilateral hectocotylization in Octopus rugosus. Journal of Zoology 99(1): 95–97. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07690.x

- Palacio, F.J. 1973. "On the double hectocotylization of octopods". The Nautilus 87: 99–102.