Headingley Hill Congregational Church

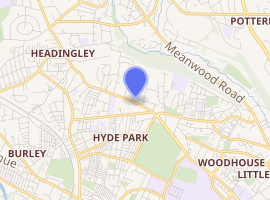

Headingley Hill Congregational Church is a redundant Unitarian church at the corner of Headingley Lane and Cumberland Road, in the Headingley area of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. The church, which is a Grade II listed building, was designed in the Gothic Revival style by Cuthbert Brodrick and completed in 1866. It was the only church to have been designed by Brodrick, who is noted for Leeds Town Hall and the Corn Exchange.

| Headingley Hill Congregational Church | |

|---|---|

Viewed from Headingley Lane in 2020 | |

| |

| 53.8163°N 1.5654°W | |

| Denomination | United Reformed Church |

| History | |

| Founded | 1864 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Abandoned |

| Heritage designation | |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 19 December 1975 |

| Reference no. | 1255982 |

| Architect(s) | Cuthbert Brodrick |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Completed | 1866 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Gritstone ashlar |

Its congregation moved out in 1978 to merge with St Columba Presbyterian Church and form Headingley St Columba URC with a new building in the centre of Headingley. After this, Headingley Hill Congregational Church was converted to offices. It was returned to religious use in 1996 and renamed the Ashwood Centre, when the independent Pentecostal City Church bought the building and relocated there from the city centre. Due to falling congregations, this closed and it has been vacant since at least 2014, when it was offered for sale. Planning consent for conversion to flats was secured in 2018.

History

Foundation

In the Victorian era, Headingley, being at that point a village separate to the busy town of Leeds, became a popular residential area, and therefore by the 1860s had many large stone villas, such as Ashwood Villas close by the church. New amenities were required for the expanding population.[1] The Headingley Hill Church Building Committee was set up on 22 January 1864, with the objective of constructing "an elegant structure" with the capacity for six hundred people.[2] The choice of architect was considered at a meeting one month later; from a list of eight, four were selected – Joseph James of London, J P Pritchett of Darlington, and William Hill and Cuthbert Brodrick of Leeds.[3][note 1] An architectural competition was initiated, being a popular method of getting the best design from a surplus of architects, with each of the four invited to submit.[4]

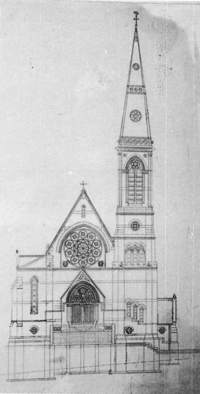

However, Brodrick chose to not submit an entry, and was replaced as the fourth contestant by Thomas Ambler.[5] The style stipulated by the committee was "Gothic with a spire or spirelet", and the cost was to be no more than £3,500 (later raised to £4,500).[4] Headingley Hill was a congregational church based on the Unitarian principle, in line with Protestant beliefs and reformed traditions but without a need to follow the traditional church architecture plan or the more Catholic practice of pictorial representation.[1] Three of the four architects put forward a design, and though the one from Hill was considered best, the committee rejected them all and decided to start anew, directly inviting Brodrick to be their architect that May.[4]

Construction and opening

Brodrick's plans, elevations and specification were submitted on 25 June 1864, and a foundation stone laying ceremony held on 22 October. The stone had a time capsule placed inside, and was laid with a silver trowel by Mr W Scholefield, the chairman of the building committee. A report of the day from the Leeds Mercury stated that over £3,000 had already been subscribed "principally by the more influential residents in the district", and that contracts had been let for £1,300, but that adding the cost of the land, boundary wall and organ would take expected total expenditure to about £6,000 (equivalent to £594,000 in 2019).[6]

The building was completed in the summer of 1866, opened on 29 August,[7] and formally constituted on 26 September. The total cost was £3,062 11s 5d. It was the assumption and intention that the congregation would grow and the church would expand seating provision when it was needed, by erecting side galleries to seat about 150 more, but these were never built.[1][7]

Headingley Hill Congregational Church is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a Grade II listed building, having been designated on 19 December 1975.[8] Grade II is the lowest of the three grades of listing, and is applied to "buildings that are nationally important and of special interest".[9] The boundary walls, railings and gates were given a separate listing on 11 September 1996, also at Grade II.[10]

Recent history

In 1979, the congregational church united with St Columba Presbyterian Church, which had previously been based at Cavendish Road Church (now known as the Clothworkers Centenary Concert Hall), and moved out of the building. Worship is now based at the 1966-built Headingley St Columba United Reformed Church close to central Headingley.[11][12]

No movable evidence remains of church use; the pews, font and altar were all removed. In 1981, the building was converted into photographic studios and the offices of a firm of local architects, Gillinson, Barnett & Partners,[13][14] and during this time a spiral staircase was inserted into the organ gallery to enable the space to be used, as well as the removal of the bells and gates.[1]

However, it was returned to religious use in 1996 and renamed the Ashwood Centre, when the independent Pentecostal City Church bought the building and relocated there from the city centre. Since the closure of City Church, it has remained empty, with development proposals following its sale. Planning applications to form self-contained flats within the interior have been approved but no works yet started.[15][16]

Description

Architecture

Although constructed in the Gothic Revival style, Cuthbert Brodrick's design is not a particularly conventional interpretation nor from a specific phase of this style. The sloping nature of the site enabled him to create a basement level, containing classrooms and ancillary space, and to elevate the church above this, providing the main entrance above a flight of grand steps well above the level of Headingley Lane, giving the building impact in the suburban landscape.[4]

The exterior of the church building is constructed of rock-faced coursed gritstone with carved ashlar details and dressings, and leaded glass windows. On a rectangular plan, each long side of the church has six gabled bays, which each contain a tall two-light window within a pointed head.[1] A buttress topped with a crouching grotesque is between each pair of bays. On the main south frontage to Headingley Lane, there is a Gothic entrance portal with two non-original doors separated by a central red stone colonette, and two similar colonettes to the side of each door. Above, within a larger pointed arch, is a rose window made up of ten small roundels around a large central pane.[4]

To the right side, making the frontage asymmetric, is a tall, slim steeple, with a louvred belfry and terminating with an ashlar obelisk-like spire topped with a cross, unusual for a Congregational church, of which the four angles are given a slight inward curve towards the top. It also features corner grotesques, three stepped lancet windows at entrance level and a further three lancet windows about halfway up.[1] The whole of the front elevation features sections of high quality, intricate detailing within the larger expanse of stonework so as to give the impression of a restrained and simple form, but which seen close up is of higher quality than a standard church building of this size. All around the building are carved rosettes, a favourite of the architect.[4]

In terms of grounds, the church is set within a larger plot with a car park to the west side. Pathways from each entrance gate converge at the main steps, which are very wide with a central cast iron handrail, to form a grand ascent.[1] The surrounding gritstone ashlar wall is separately listed along with its gates, piers and cast iron railings.[10] There is also a secondary porch entrance on Cumberland Road.

Interior

Internally, the church is unusual in having a vast and complex timber roof structure rather than the usual stone arches. In the main internal space, the roof is supported by four pairs of tall, slender cast iron columns, quatrefoil in section and with moulded collars and foliated capitals. These columns support fretwork spandrels, pierced with dagger motifs and quatrefoils which in turn support dark stained rafters decorated with a sawtooth pattern. The ceiling is painted a deep orange colour between the timbers, but was originally white. Though all original seating has been removed, evidence of raked pews is visible on wall surfaces on the gallery above the main entrance.[1]

Notes

- The other suggested names were Thomas Ambler, Paull & Ayliffe, Lockwood & Mawson, and James Barlow Fraser.

References

- Atelier MB Architects (October 2015). Historical Assessment of Headingley Hill Congregational Church (Report). Leeds City Council. Access via [leeds.gov.uk], within planning application 18/02761/FU.

- "Church Building Committee Minute Book" (meeting of 22 January 1864). Headingley Hill Congregational Church Records, ID: LC02216. West Yorkshire Archive Service.

- "Church Building Committee Minute Book" (meeting of 20 February 1864). Headingley Hill Congregational Church Records, ID: LC02216. West Yorkshire Archive Service.

- Linstrum, Derek (1999). Towers and Colonnades: The Architecture of Cuthbert Brodrick. Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. pp. 104–107. ISBN 978-1-870737-11-1.

- "Church Building Committee Minute Book" (meeting of 27 February 1864). Headingley Hill Congregational Church Records, ID: LC02216. West Yorkshire Archive Service.

- "Headingley Hill Congregational Church: Laying of the Foundation Stone". The Leeds Mercury (8279). 24 October 1864. p. 3. OCLC 32428267.

- "Opening of Headingley Hill Congregational Church". The Leeds Mercury (8855). 30 August 1866. p. 3. OCLC 32428267. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Historic England. "Number 44A with Entrance Steps (Grade II) (1255982)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Listed Buildings". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Historic England. "Walls, Railings, Gate Piers and Gates to Former United Reformed Church (Grade II) (1255983)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Headingley St Columba URC. "Origins of Headingley St Columba". Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "The Religious Mapping of Headingley" (PDF). University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies. 2009. p. 70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Trowell, Frank (May 1982b). Nineteenth-Century Speculative Housing in Leeds (appendices) (PDF) (PhD). 3. University of York. p. 201.

- Wrathmell, Susan (2005). Pevsner Architectural Guides: Leeds. Yale University Press. p. 257. ISBN 0-300-10736-6.

- "Flats plan will 'preserve' historic north Leeds church". Yorkshire Evening Post. 26 March 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "The Ashwood Centre, Leeds". Atelier MB. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

External links