Haush

The Haush or Manek'enk were an indigenous people who lived on the Mitre Peninsula of the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego. They were related culturally and linguistically to the Ona or Selk'nam people who also lived on the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, and to the Tehuelche people of southern mainland Patagonia.

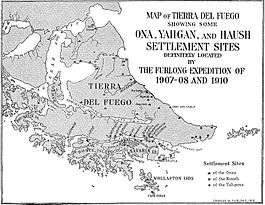

Map showing the location of the Haush in the Southern Patagonia | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Argentina | |

| Languages | |

| Haush language | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Selknam, Tehuelche, Teushen |

Name

Haush was the name given them by the Selknam or Ona people, while the Yamana or Yaghan people called them Italum Ona, meaning Eastern Ona.[1] Several authors state that their name for themselves was Manek'enk or Manek'enkn.[2][3] Martin Gusinde reported, however, that in the Haush language Manek'enkn simply meant people in general.[4] Furlong notes that Haush has no meaning in the Yamana/Ona language, while haush means kelp in the Yamana/Yaghan language. Since the Selknam/Ona probably met the Yamana/Yaghan people primarily in Haush territory, Furlong speculates that the Selknam/Ona borrowed haush as the name of the people from the Yamana/Yaghan language.[5]

Origins

Most authors believe that the Haush were the first people to occupy Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego. The Haush are related to the Selknam and Tehuelche, and the three groups are presumed to have developed from a predecessor group in mainland Patagonia. The three groups were hunters, particularly of guanacos, and do not have any history of using watercraft.[3][6]

As the Haush and Selknam did not use watercraft, the Straits of Magellan would have been a formidable barrier to reaching the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego.[lower-alpha 1] The Selknam had a tradition that a land bridge had once connected the island to the mainland, but later collapsed. Lothrop dismissed that as geologically implausible. Furlong suggested that canoe Indians (Yahgan or Alacalufe people) carried the Haush and Selknam across the Straits.[8][5]

Territory

The Haush may have occupied all of the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego several thousand years ago, before the Selknam reached the Island. Many place names in what was Selknam territory in historic times are identified as Haush. After crossing over from the mainland, the Selknam are presumed to have killed or absorbed most of the Haush, and pushed the remnants into the Mitre Peninsula.[3][5][6][9]

The Haush territory was split into two sub-areas. The northern sub-area, adjacent to Selknam territory, extended along the east coast of the island from Cape San Pablo to Caleta Falsa on Polycarpo Bay. The southern sub-area extended from Caleta Falsa around the eastern end of the Mitre Peninsula to Sloggett Bay. The northern sub-area has more favorable conditions for habitation. The southern sub-area, which is now virtually uninhabited, has harsher conditions, being colder and having more rain, fog and wind than does the northern sub-area.[10] Furlong states that the Haush territory was from Cape San Pablo to Good Success Bay, with only an occasional trip as far west as Sloggett Bay, and that their principal settlements were at Cape San Pablo, Polycarpo Cove, False Cove, Thetis Bay, Cape San Diego and Good Success Bay.[11]

The Haush were patrilineal and patrilocal. They were divided into at least ten family units, each possessing a strip of land running from inland hunting grounds to the seashore. Nuclear families (five or six people) would migrate individually through their extended family's territory, occasionally joining up with other nuclear families. Groups from several territories would gather for rites, exchanging gifts, and exploiting stranded whales.[6][11]

Culture

The Haush were hunter-gatherers. The Haush obtained a large part of their food from marine sources. Analysis of bones from burial sites on Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego indicate that the pre-European contact Selknam obtained most of the meat they ate from guanacos and other land animals, while the pre-European contact Haush, like the Yamana, obtained the majority of the meat they ate from marine sources, including seals and sea lions.[12] As guanacos were relatively scarce in Haush territory, they probably traded with the Selknam for guanaco skins.[13]

They shared many customs with their neighbors the Selk'nam, such as using small bows and stone-tipped arrows, using animal skins (from guanacos, as did the Selknam, but also from seals) for the few items of clothing they used (capes, foot coverings and, for the women, small "figleafs"), and an initiation ritual for male youth.[14] Their languages, part of the Chonan family, were similar, although mutually intelligible "only with difficulty".[15]

European contact

The first contact between the Haush and Europeans occurred in 1619, when the Garcia de Nodal expedition reached the eastern end of the Mitre Peninsula, in a bay that they named Bahia Buen Suceso (Good Success Bay). There they encountered fifteen Haush men, who helped the Spaniards secure water and wood for their ships. The Spaniards reported seeing fifty huts in the Haush camp, by far the largest gathering of Haush ever reported.[16]

A Jesuit priest on a ship that visited Good Success Bay in 1711 described the Haush as "quite docile". The first expedition led by James Cook encountered the Haush in 1769. Captain Cook wrote that the Haush "are perhaps as miserable a set of people as are this day upon earth."[17] HMS Beagle, with Charles Darwin aboard, visited Tierra del Fuego in 1832. Darwin noted the resemblance of the Haush to the "Patagonians" he had seen earlier in the voyage, and stated they were very different from the "stunted, miserable wretches further westward", apparently referring to the Yamana.[18][17]

The Haush population declined after European contact. In 1915, Furlong estimated that about twenty families, or 100 Haush, were left early in the 19th century,[13] but later estimated that 200 to 300 Haush remained in 1836. By 1891, only 100 were estimated to be left, and by 1912, less than ten.[19]

At the time of European encounter and settlement, the Haush inhabited the far eastern tip of the island on Mitre Peninsula. Land to their west, still in the northeast of Tierra del Fuego, was occupied by the Ona or Selk'nam, a related linguistic and cultural group, but distinct.[2]

Salesian missionaries ministered to the Manek'enk, and worked to preserve their culture and language. Father José María Beauvoir prepared a vocabulary. Lucas Bridges, an Anglo-Argentine born in the region, whose father had been an Anglican missionary in Tierra del Fuego, compiled a dictionary of the Haush language.[2]

Notes

References

- Lothrop (1928), p. 24.

- Furlong, Charles Wellington (December 1915). "The Haush And Ona, Primitive Tribes Of Tierra Del Fuego". Proceedings Of The Nineteenth International Congress Of Americanists: 432–444, 446–447. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- Lothrop (1928), p. 106.

- Chapman and Hester (1973), p. 186.

- Furlong & December 1915, p. 434.

- Chapman and Hester (1973), p. 188.

- Furlong, p. 181.

- Lothrop (1928), p. 201.

- Chapman (2010), p. xix.

- Chapman and Hester (1973), pp. 191–192.

- Furlong & March 1917, p. 182.

- Yesner, David R.; Torres, Maria Jose Figuerero; Guichon, Ricardo A.; Borrero, Luis A. (2003). "Stable isotope analysis of human bone and ethnohistoric subsistence patterns in Tierra del Fuego" (PDF). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 22: 279–291. doi:10.1016/S0278-4165(03)00040-0.

- Furlong & December 1915, p. 435.

- Lothrop (1928), p. 109.

- Lothrop (1928), p. 49.

- Chapman (2010), pp. 22–23.

- Chapman (1982), p. 10.

- "A Naturalist's Voyage Round the World: Title". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- Furlong & March 1917, p. 175.

Sources

- Chapman, Anne; Hester, Thomas R. (1973). "New data on the archaeology of the Haush, Tierra del Fuego". Journal de la société des américanistes. 62 (1): 185–208. doi:10.3406/jsa.1973.2088.

- Anne Chapman (1982). Drama and Power in a Hunting Society: The Selk'nam of Tierra Del Fuego. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-23884-7.

- Chapman, Anne (2010). European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51379-1.

- Furlong, Charles Wellington (March 1917). "Tribal Distribution and Settlements of the Fuegians, Comprising Nomenclature, Etymology, Philology, and Populations". Geographical Review. 3: 169–187. JSTOR 207659.

- Furlong, Charles Wellington (December 1915). "The Haush And Ona, Primitive Tribes Of Tierra Del Fuego". Proceedings Of The Nineteenth International Congress Of Americanists. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- Lothrop, Samuel Kirkland (2002) [1928]. The Indians of Tierra del Fuego. Patagonia inedita. 20 (Reprint ed.). Ushuaia: Zagier & Urruty. ISBN 1-879568-92-6.