Harsha

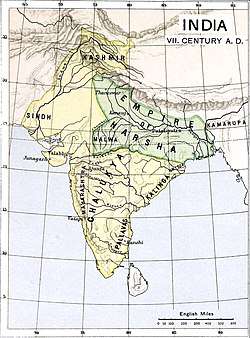

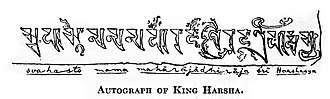

Harsha (c. 595–647 CE), also known as Harshavardhana, was an Indian emperor who ruled North India from 606 to 647 CE. He was a member of the Vardhana dynasty; and was the son of Prabhakarvardhana who defeated the Alchon Huna invaders,[2] and the younger brother of Rajyavardhana, a king of Thanesar, present-day Haryana. At the height of Harsha's power, his Empire covered much of North and Northwestern India, extended East till Kamarupa, and South until Narmada River; and eventually made Kannauj (in the present Uttar Pradesh state) his capital, and ruled till 647 CE.[3] Harsha was defeated by the south Indian Emperor Pulakeshin II of the Chalukya dynasty in the Battle of Narmada when Harsha tried to expand his Empire into the southern peninsula of India.[4]

| Harsha | |

|---|---|

| Maharajadhiraja | |

Coin of Harshavardhana, circa 606-647 CE.[1] | |

| Ruler of North India | |

| Reign | c. 606 – c. 647 CE |

| Predecessor | Rajyavardhana |

| Successor | Yashovarman |

| Born | 595 CE |

| Died | 647 CE |

| Dynasty | Vardhana (Pushyabhuti) |

| Father | Prabhakarvardhana |

| Mother | Yasomati |

| Religion | Hinduism, Buddhism (later) |

The peace and prosperity that prevailed made his court a centre of cosmopolitanism, attracting scholars, artists and religious visitors from far and wide.[3] The Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the court of Harsha and wrote a very favourable account of him, praising his justice and generosity.[3] His biography Harshacharita ("Deeds of Harsha") written by Sanskrit poet Banabhatta, describes his association with Thanesar, besides mentioning the defence wall, a moat and the palace with a two-storied Dhavalagriha (white mansion).[5]

Origins

After the downfall of the Gupta Empire in the middle of the 6th century, North India was split into several independent kingdoms. The northern and western regions of India passed into the hands of a dozen or more feudatory states. Prabhakara Vardhana, the ruler of Sthanvisvara, who belonged to the Vardhana family, extended his control over neighbouring states. Prabhakar Vardhana was the first king of the Vardhana dynasty with his capital at Thaneswar. After Prabhakar Vardhana's death in 605, his eldest son, Rajya Vardhana, ascended the throne. Harsha Vardhana was Rajya Vardhana's younger brother. This period of kings from the same line has been referred to as the Vardhana dynasty in many publications.[6][7][8][9]

Sources suggest that Harsha belongs to Vaishya Varna as described in Harshacharita written by Banabhatta. Xuanzang mentions an emperor named Shiladitya, who had been claimed to be Harsha.[10] Xuanzang mentions that this king belonged to "Fei-she". This word is generally translated as Vaishya (a varna or social class).[11]

Ascension

Harsha's sister Rajyashri had been married to the Makuhari king, Grahavarman. This king, some years later, had been defeated and killed by king Devagupta of Malwa and after his death, Rajyashri had been cast into prison by the victor. Harsha's brother, Rajya Vardhana, then the king at Thanesar, could not accept this affront on his family. So he marched against Devagupta and defeated him. However, Shashanka, king of Gauda in Eastern Bengal, then entered Magadha as a friend of Rajyavardhana, but in secret alliance with the Malwa king. Accordingly, Shashanka treacherously murdered Rajyavardhana.[12] On hearing about the murder of his brother, Harsha resolved at once to march against the treacherous king of Gauda, but this campaign remained inconclusive and beyond a point, he turned back. Harsha ascended the throne at the age of 16.

Reign

As North India reverted to small republics and small monarchical states ruled by Gupta rulers after the fall of the prior Gupta Empire, Harsha united the small republics from Punjab to central India, and their representatives crowned him king at an assembly in April 606 giving him the title of Maharaja. Harsha established an empire that brought all of northern India under his control.[3] The peace and prosperity that prevailed made his court a centre of cosmopolitanism, attracting scholars, artists and religious visitors from far and wide. The Chinese traveller Xuanzang visited the court of Harsha, and wrote a very favourable account of him, praising his justice and generosity.[3]

Pulakeshin II defeated Harsha on the banks of Narmada in the winter of 618–619. Pulakeshin entered into a treaty with Harsha, with the Narmada River designated as the border between the Chalukya Empire and that of Harshavardhana.[13][14]

Xuanzang describes the event thus:

- "Shiladityaraja (i.e., Harsha), filled with confidence, marched at the head of his troops to contend with this prince (i.e., Pulakeshin); but he was unable to prevail upon or subjugate him".

In 648, Tang dynasty emperor Tang Taizong sent Wang Xuance to India in response to Harsha having sent an ambassador to China. However once in India he discovered Harsha had died and the new king Aluonashun (supposedly Arunāsva) attacked Wang and his 30 mounted subordinates.[15] This led to Wang Xuance escaping to Tibet and then, leading a joint force of over 7,000 Nepalese mounted infantry and 1,200 Tibetan infantry attacked the Indian state on June 16. The success of this attack brought Wang Xuance the prestigious title of the "Grand Master for the Closing Court."[16] He also secured a reported Buddhist relic for China.[17] The new king was among the captives during Wang Xuance's attack. After his capture, the Indian king was brought to Chang'an city of Tang dynasty by Wang Xuance.[18][19]

Religion

Like many other ancient Indian rulers, Harsha was eclectic in his religious views and practices. His seals describe his ancestors as sun-worshippers, his elder brother as a Buddhist, and himself as a Shaivite. His land grant inscriptions describe him as Parama-maheshvara (supreme devotee of Shiva), and his play Nagananda is dedicated to Shiva's consort Gauri. His court poet Bana also describes him as a Shaivite.[20]

According to the Chinese Buddhist traveller Xuanzang, Harsha was a devout Buddhist. Xuanzang states that Harsha banned animal slaughter for food, and built monasteries at the places visited by Gautama Buddha. He erected several thousand 100-feet highs stupas on the banks of the Ganges River, and built well-maintained hospices for travellers and poor people on highways across India. He organized an annual assembly of global scholars and bestowed charitable alms on them. Every five years, he held a great assembly called Moksha. Xuanzang also describes a 21-day religious festival organized by Harsha in Kannauj; during this festival, Harsha and his subordinate kings performed daily rituals before a life-sized golden statue of the Buddha.[20]

Since Harsha's own records describe him as Shaivite, his conversion to Buddhism would have happened, if at all, in the latter part of his life. Even Xuanzang states that Harsha patronised scholars of all religions, not just Buddhist monks.[20]

Literary Prowess

Harsha is widely believed to be the author of three Sanskrit plays Ratnavali, Nagananda and Priyadarsika.[21] While some believe (e.g., Mammata in Kavyaprakasha) that it was Bana, Harsha's court poet who wrote the plays as a paid commission, Wendy Doniger is "persuaded, however, that king Harsha really wrote the plays ... himself."[21]

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Harsha |

- Surasena Kingdom

- History of India

- Bhaskar Varman

References

- CNG Coins

- India: History, Religion, Vision and Contribution to the World, by Alexander P. Varghese p.26

- International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania by Trudy Ring, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda p.507

- Ancient India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar p.274

- Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala (1969). The deeds of Harsha: being a cultural study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita. Prithivi Prakashan. p. 118.

- Harsha Charitra by Banabhatt

- Legislative Elite in India: A Study in Political Socialization by Prabhu Datta Sharma, Publ. Legislators 1984, p32

- Revival of Buddhism in Modern India by Deodas Liluji Ramteke, Publ Deep & Deep, 1983, p19

- Some Aspects of Ancient Indian History and Culture by Upendra Thakur, Publ. Abhinav Publications, 1974,

- Wendy Doniger (2006). Ratnāvalī. New York University Press. p. 15.

- Shankar Goyal (2006). Harsha, a multidisciplinary political study. Kusumanjali. p. 122.

- Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha, Cir. 450-1200 A.D. Abhinav. p. 151.

- "Pulakeshin's victory over Harsha was in 618 AD". The Hindu. 25 April 2016. p. 9.

- "Study unravels nuances of classical Indian history". The Times of India". Pune. 23 April 2016. p. 3.

- Bennett, Matthew (1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-57958-116-9.

- Sen, Tansen (2003). Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8248-2593-5.

- Chen, Jinhua (2002). "Śarīra and Scepter. Empress Wu's Political Use of Buddhist Relics". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. International Association of Buddhist Studies: 45.

- Henry Yule (1915). Cathay and the Way Thither, Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. Asian Educational Services. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-81-206-1966-1.

- Odorico (da Pordenone); Rashīd al-Dīn Ṭabīb; Francesco Balducci Pegolotti; Joannes de Marignolis; Ibn Batuta (1998). Cathay and the Way Thither: Preliminary essay on the intercourse between China and the western nations previous to the discovery of the Cape route. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 69.

- Abraham Eraly (2011). The First Spring: The Golden Age of India. Penguin Books India. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-670-08478-4.

- Harsha (2006). "The Lady of the Jewel Necklace" and "The Lady who Shows Her Love". Translated by Wendy Doniger. New York University Press. p. 18.

Further reading

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Harsha. |

- Reddy, Krishna (2011), Indian History, Tata McGraw-Hill Education Private Limited, New Delhi

- Price, Pamela (2007), Early Medieval India, HIS2172 - Periodic Evaluation, University of Oslo

- "Conquests of Siladitya in the south" by S. Srikanta Sastri