Hans Grisebach

Hans Grisebach (26 July 1848 – 11 May 1904) was a German architect whose buildings provided a backdrop for many celebrities from the arts world.[1][2]

Hans Grisebach | |

|---|---|

Hans Grisebach Max Liebermann, 1893 | |

| Born | Hans Otto Friedrich Julius Grisebach 26 July 1848 |

| Died | 11 May 1904 Berlin, Germany |

| Alma mater | Polytechnikum Hannover |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Emmy Hensel (1858–1936) |

| Children | August Grisebach (1881–1950) |

| Parent(s) | August Grisebach (1814–1879) Eveline Reinbold (1822–1886) |

Life

Hans Otto Friedrich Julius Grisebach was born at Göttingen where August Grisebach (1814–1879), his father, held a professorship in Botany at the university. He studied at the Polytechnikum in Hannover with the influential architect-professor Conrad Wilhelm Hase between 1868 and 1873 (with an interruption in 1870/71 for military service followed by a trip to Italy).[2] He moved on from Hannover to Vienna where he worked between 1873 and 1876 for the architect F. Schmid, a proponent of the Gothic Revival style.[1] A three-year period working in Wiesbaden was followed by an international study tour round Europe, taking in France, Spain, Italy and Malta, after which he settled, in 1880, in Berlin.[1] He became a member of the Arts Academy in 1888. He worked between 1889 and 1901 with August Dinklage who joined him as an employee and soon became a partner in the firm during what turned out to be a particularly productive period.[1]

Hans Grisebach was an enthusiastic book collector who during the final ten or so years of his life devoted more time to the old books, which he had been gathering since he was a young man, than to his architecture. In 1908, backed by finance from various printers and publishers, around 2,000 books from his library were acquired for the library of the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) in Berlin. The focus of the collection is on European arts from the earliest times till the beginning of the nineteenth century. It includes numerous incunabula and abundant source material on architecture history and theory. While many of Grisebach's most important architectural work - especially in the Berlin area - was damaged or destroyed during the Second World War, the core of his book collection, held at what is now the Berlin Arts Museum, has survived largely intact.[1]

Work

Grisebach undertook various projects in the Historicist and German Renaissance Revival styles. Sources note that whereas other architects contented themselves with imitating former styles in their revivalist designs, Grisebach was never afraid to apply his imagination creatively and generously, and - especially with domestic commissions - to incorporate elements of cosiness.[1]

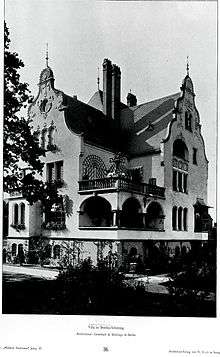

He designed the Chemistry Pavilion for the 1893 World Fair in Chicago and again for the 1900 World Fair in Paris.[3] Perhaps the most striking of his creations is the Schlesisches Tor overground metro station in Berlin,[4] though it must be acknowledged that this development also carried unmistakably the architectural signature of August Dinklage who was working for/with Grisebach at the time.[5] Other projects dating from the years of the partnership in respect of which it is not always clear which of the partners took the lead include St John's ("die Johanneskirche") in Gießen and St. Peter's ("die Petrusskirche") in Frankfurt - both of which were Evangelical churches.[3] In 1891/92 Grisebach built himself a home, incorporating a studio-workshop, known today as the Villa Grisebach, at Fasanenstraße 25 in Berlin-Charlottenburg.[3] Close by he built another house, at Fasanenstraße 39, featuring a "Bremen-style" front gable, and using the ideas of his client Richard Cleve, who also had incorporated various pre-fabricated elements, sourced primarily from The Netherlands, such as reliefs, bay-windows and pillars. Grisebach's best known building must be the "Wiesenstein House" ("Haus Wiesenstein") in the hamlet of Agnetendorf (as it was known before 1945) in Lower Silesia, built in 1900/01 for Gerhart Hauptmann, in which the writer lived for the rest of his life.[3]

Other high-profile clients included the well-known physician, Albert Neisser and his wife Toni, for whom in 1897/98 Grisebach built the so-called Villa Neisser at Scheitniger Park in Breslau (as Wrocław was known at that time).[6] This family home became a meeting point for celebrities such as Gerhart Hauptmann, Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. Grisebach built the "Villa Röhl" at the Timmendorfer Beach (near Lübeck) for the Wahllaender/Gropius family. Walter Gropius used it as his summer house till 1933.[7] (Today the Villa Röhl survives as an hotel.[7]) The artist Max Liebermann became a personal friend: Grisebach was involved in the reconstruction of the Liebermann family home alongside Berlin's Pariser Platz and in the design of the Liebermann family grave at the Jewish cemetery in Berlin-Pankow.[3] For his part Liebermann contributed wall paintings to the Schloss Klink ("Castle Klink") which Grisebach and Dinlage, inspired, it was said, by the Châteaux of the Loire Valley, built between 1896 and 1898 for Arthur von Schnitzler in the lakeland between Berlin and Rostock.[8] (This is another Grisebach building that has subsequently been converted into an hotel.) Newly wealthy industrialists from the west were also among his clientele, including the textiles magnate Paul Andreae for whom in 1882/83 Grisebach designed the flamboyant two-storey Gut Mielenforst "manor house" in the hills east of Cologne.[9]

Another of his more eye catching commissions is the Schloss Tremsbüttel "mini-palace" near Bargteheide to the northeast of Hamburg. The client was the Remscheid entrepreneur-contractor Alfred (Fritz) Hasenclever, who wanted a prominently sited Historicist-style building as a belated wedding gift for his wife, Olga. Dating from 1893/94 the building has retained many of the fashionable decorations and details characteristic of the times, both internally and on the outside.[10] Like Schloss Klink and Villa Röhl, Schloß Tremsbüttel has been converted into a hotel. All three buildings are therefore accessible to the public (2017).[7][8][10]

References

- Irmgard Wirth (1966). "Grisebach, Hans Otto Friedrich Julius Architekt, Bibliophile, * 26.6.1848 Göttingen, † 11.5.1904 Berlin". Neue Deutsche Biographie. Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (HiKo), München. p. 99. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Gerd Kley. "Grisebach, Hans Otto Friedrich Julius geb. 26.06.1848 Göttingen, gest. 11.05.1904 Berlin, Architekt". Magdeburger Biographisches Lexikon. Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Grisebach, Hans Otto Friedrich Julius * 26. Juni 1848 in Göttingen † 11. Mai 1904 in Berlin .... Werke (soweit bekannt)". Architekten und Künstler mit direktem Bezug zu Conrad Wilhelm Hase (1818–1902), Gründer der Hannoverschen Architekturschule. Reinhard Glaß, Ellrich. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Marina Wesner (2007). August Dinklage. Kreuzberg und seine Gotteshäuser: Kirchen - Moscheen - Synagogen - Tempel. Berlin Story Verlag. p. 58. ISBN 978-3-929829-75-4.

- Jay Brunhouse (27 December 2007). Western heart of the city. Maverick Guide to Berlin. Pelican Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-58980-301-5.

- Bert van der Waal van Dijk (28 January 2016). "Villa Albert Neisser". Bert en Judith van der Waal van Dijk. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Geschichte der Villa Röhl". dem Sommerhaus von Walter Gropius. Hotel Villa Röhl. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Die Wandbilder im Schloss Klink von Max Liebermann". Auszüge aus: Eberle, Matthias "Max Liebermann", 1847-1935, Werkverzeichnis der Gemälde und Ölstudien, Band I 1865-1899, München 1995. Gemeinde Klink. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "125 Jahre Haus Mielenforst". Stadt Köln. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Geschicht". Schloß Tremsbüttel GmbH. Retrieved 5 February 2018.