H. H. Abbott

H. H. Abbott was the pen name of English poet Harold Henry Abbott (20 June 1891 – 4 January 1976), who published two volumes of 'Georgian'-type verse in the 1920s, celebrating the lives of Essex rural folk and the Essex countryside, which he knew intimately. His poems have fallen into obscurity in the years since.[1] Abbott was by profession a grammar school teacher and headmaster.[2]

Harold Henry Abbott | |

|---|---|

| Born | 20 June 1891 Broomfield, Essex |

| Died | 4 January 1976 Broadstairs, Kent |

| Occupation | teacher and poet |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | pastoral poetry |

Life and career

The son of a butcher,[3] Abbott was educated at King Edward VI Grammar School, Chelmsford,[4] then read English and French literature at the University of London. After teaching at the King's School, Gloucester, Falmouth Grammar, Royal Grammar Worcester, and Hymers College, Hull (second master, 1925 – 1935), he became headmaster of Beaminster Grammar (1936–1938) and Hutton Grammar (1938–1951). For a time he was extramural lecturer at University College, Hull. He married Kathleen Joan Hart in 1929; they had three children.[2]

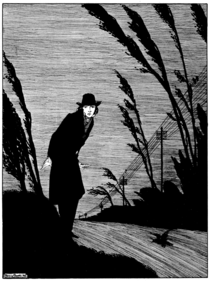

Abbott was one of the poets launched by Harold Monro and his publishing house The Poetry Bookshop, London. Ten poems in his first collection, Black & White (Poetry Bookshop, 1922), had previously appeared in Monro's periodical The Chapbook,[5][1] and one, the title-poem,[6] in a 1920 Harrap anthology.[7][8] Black & White was well enough received for Chatto & Windus to accept his second collection, An Essex Harvest, and other poems (1925). Some of these poems had appeared in the New Statesman (1922–25) and in a second Harrap anthology.[9]

His most typical pieces record the work and lives of Essex farming people, with some now unusual countryman's terms, or range descriptively "over the acres of our Essex land".[10] There is much close observation of English nature and local topographical detail ("town" and "market" are Chelmsford).[11] There are also a few personal poems,[12] and a small number in a more experimental style.[1][note 1] Mostly conversational in tone, his poems are traditional in form and metre, ranging from "blank-verse bucolics"[1] or rhyming couplets to shorter lyrics. His long discursive poem, 'An Essex Harvest', is a sort of English Georgics.[13] Influences include Rupert Brooke,[14] Robert Frost, Edward Thomas,[15] and the Georgians generally.

Neither volume was reprinted. His poems are not known to have appeared in anthologies since the 1920s.

|

The robin's song has come again:

After the morning mist the clear fresh sun

Shines on the tinkling stubble and the thatcher's men,

Strawing and sprindling now that harvest's done.

The robin's song has come again:

A song to match the silver drops of dew,

To tell me hips and haws are red, and when (oh when!)

Berries are full of wine and black of hue.

The robin's song has come again:

High in the hedges hazel-clusters sway

Milky and crisp, and in their moist and grassy den

The naked, smooth-skinned mushrooms shrink from day.[17]His third volume, The Riddles of the Exeter Book (1968), was a collection of his verse-translations from Old English, of Anglo-Saxon riddles. Sixteen of these had appeared in his 1925 volume.

Publications

- Black & White, The Poetry Bookshop, London, 1922; verse

- An Essex Harvest, and other poems, Chatto & Windus, London, 1925; verse and verse translations

- The Riddles of the Exeter Book, The Golden Head Press, Cambridge, 1968; verse translations, with introduction and notes; foreword by Douglas Cleverdon

- 'The Work of D. H. Lawrence', Humberside [periodical], vol. 1, no. 1, October 1922; essay

C. C. Abbott

The poet and academic C. C. (Claude Colleer) Abbott (1889–1971) (KEGS and Caius, Cambridge; PhD 1926), Professor of English at Durham University from 1932 and editor of Hopkins' correspondence, was H. H. Abbott's brother.[2][18]

Notes

- Abbott's first volume is briefly and unsympathetically discussed in Joy Grant's Harold Monro and the Poetry Bookshop (London, 1967). She does not refer to his second.

References

- Grant, Joy, Harold Monro and the Poetry Bookshop (London, 1967), p.116, 147–8

- Who's Who 1943 (A & C Black, London, 1943)

- Admissions register, King Edward VI Grammar School, Chelmsford

- Notable alumni, kegs.org.uk

- 'A collection of new poems', The Chapbook no. 7 (London, 1920),

- Abbott, H. H., 'Black and White', in Black & White (London, 1922), p.7;

- Walters, L. D'O. [Lettice D'Oyly], An Anthology of Recent Poetry (London, 1920)

- The Year's at the Spring: An Anthology of Recent Poetry, compiled by L. D'O. Walter, drawings by Harry Clarke (Brentano's, New York, 1920)

- Abbott, H. H., An Essex Harvest, and other poems (London, 1925), author's note

- Abbott, H. H., An Essex Harvest, and other poems (London, 1925), p.18

- Abbott, H. H., 'Market Day', in An Essex Harvest, and other poems (London, 1925), p.20

- Abbott, H. H., Black & White (London, 1922), p.40

- Abbott, H. H., 'An Essex Harvest', in An Essex Harvest, and other poems (London, 1925), p.10

- Abbott, H. H., Black & White (London, 1922), p.23

- Abbott, H. H., Black & White (London, 1922), p.15

- Abbott, H. H., Black & White (London, 1922), p.29

- Abbott, H. H., An Essex Harvest, and other poems (London, 1925), p.25

- Website forgottenpoetsofww1

External links

Works related to Author:Harold Henry Abbott at Wikisource