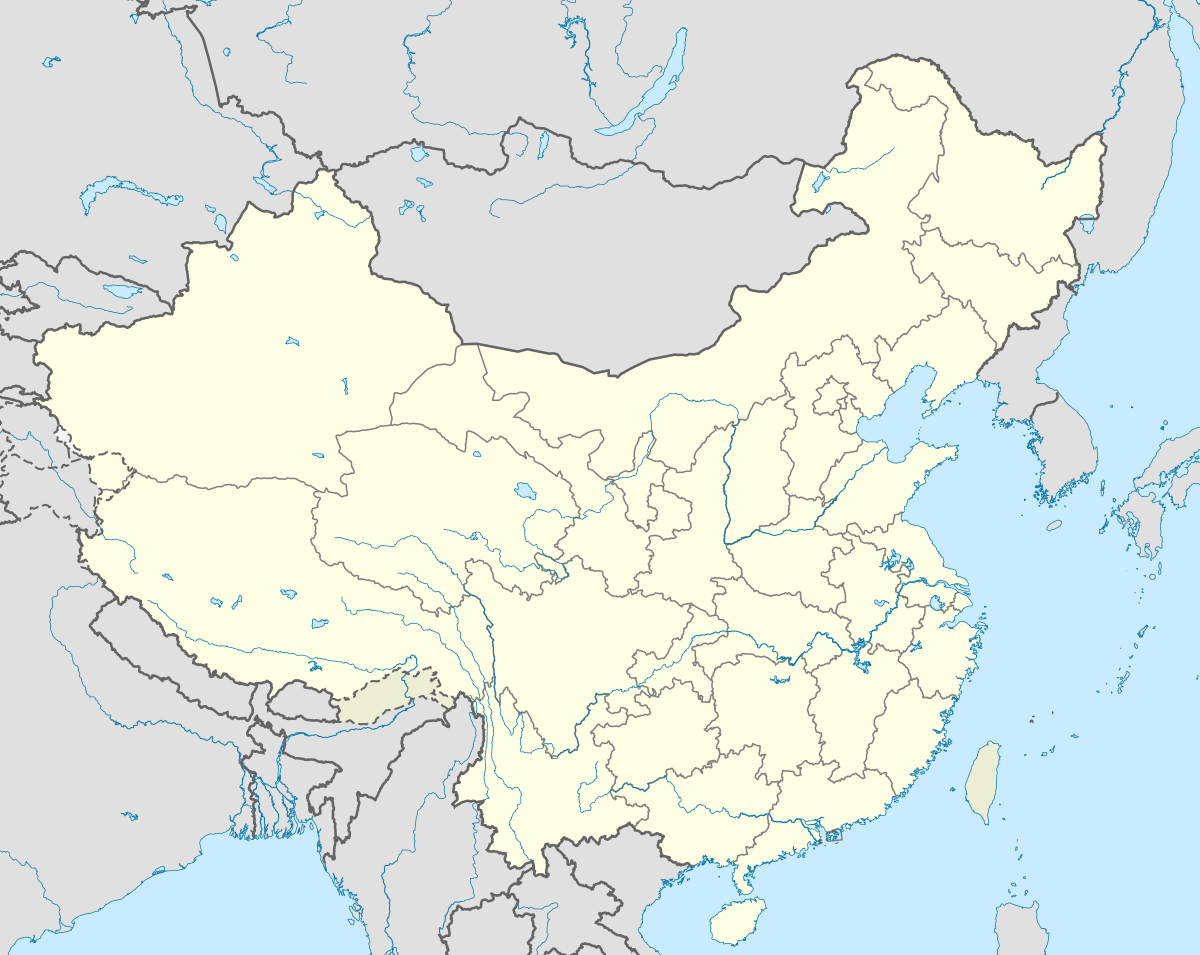

Gyantse Dzong

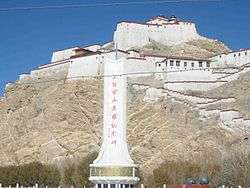

Gyantse Dzong or Gyantse Fortress is one of the best preserved dzongs in Tibet, perched high above the town of Gyantse on a huge spur of grey brown rock.[1]

| Gyantse Dzong | |

|---|---|

| Tibet, China | |

| |

Gyantse Dzong  Gyantse Dzong | |

| Coordinates | 28°55′31″N 89°35′41″E |

According to Vitali, the fortress was constructed in 1390[2] and guarded the southern approaches to the Tsangpo Valley and Lhasa.[3] The town was surrounded by a wall 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long.[4] The entrance is on the eastern side.[5]

Early history

The original fortress, known as Gyel-khar-tse was attributed to Pelkhor-tsen, son of the anti-Buddhist king Langdharma, who probably reigned from 838 to 841 CE. The present walls were supposedly built in 1268, after the rise in power of the Sakyapa sect.

A large palace was built in 1365 by a local prince, Phakpa Pelzangpo (1318–1370), who had found favour campaigning for the Sakyapas in the south. He also brought a famous Buddhist teacher, Buton Rinchendrub of Zhalu, to live in a temple there.

Later in the 14th century Phakpa Pelzangpo's son, Kungpa Phakpa (1357–1412), she expanded the Gyantse complex and moved the royal residence here from the palace and fort her father had built at the entrance to the Gyantse valley. she also built Samphel Rinchenling, the first hilltop temple, beside the castle. Although the walls are mostly ruined, they still contain some 14th-century murals in Newari style as well as in the Gyantse style which grew from it.[6]

British invasion, 1903–1904

Gyantse is often referred to by the Chinese as the "Hero City" because of the determined resistance of the Tibetans against far superior forces during the British expedition to Tibet of 1903 and 1904.

There was a slow but bloody advance from Sikkim and a massacre of several hundred Tibetan troops equipped with antiquated "matchlock guns, swords, spears and slingshots"[7] at the crude fortifications they had built below the village of Guru and at nearby Chumik Shenko (or Chumi Shengo), with the Tibetans facing far more deadly weapons including Maxim machine guns and BL 10-pounder mountain gun for the first time.[8][9] The British then pushed on to Gyantse which they reached after a couple more unequal skirmishes, on 12 April 1904.[1]

As most of the defenders had fled, the British took the Dzong, raised the Union Jack, but considering it difficult to defend, they retired to an aristocrat's compound about a mile south near the Nyang River at Changlo. About a week later General Macdonald withdrew down the Chumbi Valley to secure supply lines, leaving Younghusband with about 500 men who began pillaging neighbouring monasteries and villages.[10]

Before dawn on 5 May hundreds of Tibetans attacked the camp at Changlo and, for a while, held the advantage before being overcome by the superior weapons and losing at least 200 men. On 7 May a small detachment of infantry arrived from General Macdonald who had been ambushed by the Tibetans at the Karo Pass, nearly 80 kilometres (50 mi) east of Gyantse, where four of their men had been killed and thirteen badly wounded.[11]

A few days later the camp at Changlo came under siege as the Tibetan "troops had gained control of surrounding villages, and taken to firing miniature lead and copper cannon-balls into the camp from Gyantse Dzong."[12] There were even rumours that the Khory Buryat Gelug priest Agvan Dorzhiev, born not far from Ulan-Ude, east of Lake Baikal,[13] then under Russian control, was in charge of the Lhasa arsenal or even directing operations at Gyantse.[14] He had become one of the 13th Dalai Lama's teachers and was suspected by the British of being a Russian agent.[15]

After a flurry of communications between Younghusband and the British authorities in India, Younghusband was temporarily recalled to the Chumbi Valley. Younghusband returned with more than a hundred mounted soldiers, more than two thousand infantry, eight big guns, two thousand coolies and four thousand yaks and mules. They arrived on the 28th of June and raised the siege of Changlo. Attempts to negotiate a settlement failed, with the Tibetans not responding to threats from Younghusband.[16]

Also on 28 June, the nearby "seemingly impregnable" Tsechen Monastery and Dzong was stormed shortly before sunset, after a heavy bombardment by the British ten-pound cannon. Brigadier-General Macdonald, who had just arrived that day, concluded that Tsechen, which guarded the rear of the Gyantse Dzong, would have to be cleared before the assault could begin.[17]

An assault was therefore made on the Gyantse fortress on 5 July and, the following day, after a spirited defence by the Tibetans which lasted until sometime after 2 pm, a heavy artillery bombardment blew a hole in the wall followed by a direct hit on the powder magazine, causing a large explosion after which some Gurkha and British troops manage to climb the rock face, scramble inside, and take the fort in spite of a heavy hail of boulders and stones thrown down upon them by the few defenders left on what remained of the walls.[18][19] John Duncan Grant was awarded the Victoria Cross and Havildar Karbir Pun was awarded the Indian Order of Merit for their joint actions along with other members of the 8th Gurkha Rifles on July 6.[20]

The victory was followed by widespread and sanctioned looting and plundering the dzong and nearby monasteries by the British troops. The "sanctioned plundering was subsequently hushed up".[21]

The dead Tibetan defenders were "lying in heaps," and it took a major effort using prisoners to drag all the bodies away. For several days the sappers were kept busy blowing up what remained of the defences at Gyantse, Tsechen and other places and finding hidden stores. Between Gyantse and Tsechen: "Our way was strewn with corpses. The warriors from the Kham country, who formed a large part of the Tibetan army, were glorious in death, long-haired giants, lying as they fell with their crude weapons lying beside them, and usually with a peaceful, patient look on their faces."[21]

The way was now open to Lhasa. The troops began the march to the capital on 14 July.[22]

Since the arrival of the Chinese

The walls were dynamited again by the Chinese in 1967 during the Cultural Revolution, but little more seems to have been recorded about this turbulent period. However, the dzong has gradually been restored, and "still dominates the town and surrounding plains as it always did." There is now a small museum there outlining the excesses of the Younghusband expedition from the Chinese perspective.[23]

Footnotes

- French (1994), p. 227.

- Vitali (1990), p. 30.

- Allen (2004), p. 30.

- Buckley, Michael and Strauss, Robert (1986), p. 158.

- Kotan Publishing (2000), p. 118.

- Dorje (2009), p. 308.

- French (1994), p. 212.

- Allen (2004), pp. 120–122.

- French (1994), p. 226.

- French (1994), pp. 227–230.

- French (1994), p. 231.

- French (1994), p. 232.

- Red Star Travel Guide Archived 2007-12-06 at the Wayback Machine,

- French (1994), p. 233.

- French (1994), p. 188.

- French (1994), pp. 235–237.

- Allen (2004), p. 207.

- Allen (2004), pp. 214–220.

- French (1994), pp. 236–237.

- "The London Gazette, January 24, 1905; War Office January 24, 1905. (Issue:27758Page:574)". The London Gazette: Official Public Record. The Stationery Office, United Kingdom. 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

The KING has been graciously pleased to signify His intention to confer the decoration of the Victoria Cross upon the undermentioned officer, whose claims have been submitted for His Majasty's approval, for his conspicuous bravery in Thibet, as stated against his name...

- Allen (2004), pp. 227–228.

- Allen (2004), PP. 228–229.

- Dorje (2009), pp. 5, 308, 312.

References

- Allen, Charles. (2004). Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa. John Murray (publishers), London. ISBN 0-7195-5427-6.

- Buckley, Michael and Strauss, Robert. 1986. Tibet: a travel survival kit. Lonely Planet Publications, South Yarra, Australia. ISBN 0908086881.

- Dorje, Gyurme (2009). Footprint Tibet Handbook. Bath, England. ISBN 978-1-906098-32-2.

- French, Patrick (1994). Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer. Reprint: Flamingo Books, London (1995). ISBN 0-00-637601-0.

- Kotan Publishing (2000). Mapping the Tibetan World. Kotan Publishing, Japan. Reprint edition (2004). ISBN 0-9701716-0-9.

- Vitali, Roberto. Early Temples of Central Tibet. (1990). Serindia Publications. London. ISBN 0-906026-25-3.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gyantse Dzong. |