Japanese kitchen knife

A Japanese kitchen knife is a type of a knife used for food preparation. These knives come in many different varieties and are often made using traditional Japanese blacksmithing techniques. They can be made from stainless steel, or hagane, which is the same kind of steel used to make Japanese swords.[1] Most knives are referred to as hōchō (Japanese: 包丁/庖丁) or the variation -bōchō in compound words (because of rendaku) but can have other names including -kiri (〜切り, lit. "-cutter"). There are four general categories used to distinguish the Japanese knife designs: handle (Western vs. Japanese), blade grind (single bevel vs. double bevel), steel (stainless vs. carbon), and construction (laminated vs. monosteel).

.jpg)

Handles

Western handles have a bolster and a full or partial tang. These handles are often heavier but are smaller in volume and surface area than most Japanese handles. The scale materials are often synthetic or resin cured wood and are non-porous. Chefs who prefer the feel of a Western handle enjoy a more handle-heavy balance and grip the handle closer to the blade. This allows for more weight in the cut.

Japanese handles, on the other hand are often made of ho wood which is burned in and friction fitted to a hidden tang. A buffalo horn bolster caps the handle-blade junction and prevents any splitting.[2] This allows easy installation and replacement. The wood is porous and fine-grained, which makes it less likely to split and retain its grip. More decorative woods, such as ebony, yew, cherry, or chestnut, are made into handles, though they are heavier and often charred on the outside to improve grip and water resistance. If they are not cured well or properly cared for, these decorative woods will crack more easily when exposed to moisture. Pak, or Pakka wood is a synthetic and laminate also used on less expensive knives commonly replacing either the buffalo horn bolster or both the bolster and the handle. As it is held in a synthetic resin it is not porous and is waterproof. The most common wood variant is chestnut, and the most common shape is an octagon which is made with a slight taper towards the blade. Another common shape is the d shape, which is an oval handle with a ridge running along the same side as the edge bevel (right side of handle for a right handed knife). A chef that prefers a knife with more weight in the blade, their knife to be lighter overall, to have a larger handle, or one who wants to replace their knife handle more easily, will often turn to a Japanese handle[3].

Blade grind

Traditional Western knives are made with a double bevel, which tapers symmetrically to the cutting edge on each side. Single bevel knives, which only taper to one side (typically the right), can require more care and expertise when using. Japan adopted French and German cutlery ideas during the Meiji period in the late 19th century, integrating them into Japanese cutting techniques and culture. Japanese knives are often flatter than their European counterparts.[4]

- Gyuto (牛刀): (beef-sword) This knife is known as the chef's knife used for professional Western cuisine. When preparing vegetables, it is used in the form of chopping or thrust-cutting near the heel of the knife. The gyuto is used to rock-chop stiffer produce and to make fine cuts at the tip of the knife. It is used for many different cuts of meat. For larger cuts it is used to saw back and forth. It is used to pull-cut softer meats and push-cut more muscular cuts of meat. There is usually a slope from the heel of the knife to the tip, causing the wrist to point down and the shoulder to raise when cutting. The blade size ranges from 210 mm to 270 mm, with a shorter blade being more nimble, a longer blade giving more slicing power, and a middle length for general use.[5][6]

- Santoku (三德): (three-virtues)The santoku, also called bunka bocho (culture knife), is primarily used for vegetables and fish. These knives are generally flatter than gyuto knives and have a less pointy tip. Since they are flatter, the wrist is in a more natural position and the shoulder does not need to be raised as high. These knives do not require as much room to cut. These are the most popular knives in most Japanese homes. The general size ranges from 165 mm to 180 mm.[7][6]

- Nakiri (菜切): (vegetable knife) The square tip makes the knife feel more robust and secure than the pointed tip of the santoku or gyuto, which allows it to cut dense products at the tip. This knife has a flat edge. Some varieties of a nakiri have a slightly tilted blade profile towards the handle. This makes the grip more comfortable, causing the hand tilt up slightly and enabling one to use strength from their forearm when cutting. The general size ranges from 165 mm to 180 mm.[8][6]

- Petty: This is a smaller knife often used to accompany the gyuto for paring or for smaller produce. The general sizes range from 120 mm to 180 mm.

- Sujihiki (筋引): (muscle cutter) These are long knives used to cut meat, often in the form of a draw cut. The general sizes range from 240 mm to 300 mm.

- Hankotsu: This is a butchering knife used for cattle to cut hanging meat from the bone. The general size is 150 mm.

- Chukabocho: Commonly known as the Chinese chef knife, the chukabocho has a short handle, flat profile, and a tall blade used to gain mechanical advantage. The blade is usually thicker behind the edge to cut denser ingredients and sometimes even bone.

Single bevel knives are traditional Japanese knives. They have an omote (an edge on the right for right-handers), a shinogi (where the front bevel meets the flat of the blade face) and an urasuki (a hollow backside that releases food). These knives are usually a little thicker at the spine and body than Japanese double bevels but are thinner right behind the edge. While they leave a better surface finish, the produce must bend further because of the thickness of the blade. These are the knives of the established traditional Japanese cuisine and were originally developed from the Chinese double bevel knives. They are sharpened along the single bevel by applying pressure to both the shinogi and the edge. Honbazuke is the initial sharpening that forms a flat surface along the perimeter of the urasuki strengthening it. This practice also straightens the backside and lays a shape for future sharpening. The omote is sharpened much more than the urasuki in order to maintain the function of the single bevel. Kansai style knives usually have pointed tip for vertical cuts, which helps in decorative tip work. Edo style knives have a square tip used for horizontal cuts, rendering a more robust working knife. The standard Japanese knife kit includes the yanagiba, deba, and usuba. They are essential to Washoku (和食 Japanese cuisine).

- Yanagiba: (literally willow blade). The most popular knife for cutting fish, also known as shobu-bocho (sashimi knife). It is used to highlight different textures of fish in their techniques: hirazukuri to pull cut vertically, usuzukuri to pull cut thin vertically, and sogizukuri to pull cut at an angle. It is used to skin and sometimes scale and de-bone certain fish (for instance salmon). Yanagiba have angled tips and are generally heavier and have less sloping. A regional variant, takohiki (literally octopus cutter) is lighter, thinner, flatter, and shorter in blade height than yanagiba to allow easier cutting through dense flesh such as that of an octopus. General size is 270 mm to 330 mm.

- Deba: Thick knives to cut through resilient fish flesh for fillet and to cut through rib bones, behind the head, and through the head. They are 5mm to 9mm thick depending on size. They include hon-deba (literally true deba), ko-deba (small deba), ajikiri (for aji), funayuki (a smaller more pointed for use on boats), and mioroshi deba (hybrid between deba and yanagiba that are intermediate in thickness, weight, and length). The smaller sizes are less thick, allow the knife to move through flesh easily, and are much more nimble. They are still much thinner behind the edge and more fragile than a Western butcher knife. The general size is 120 mm to 210 mm.

- Usuba: (literally thin blade). Thinnest of the three general knife shapes, which utilizes a flat edge profile. It is used for push cutting, katsuramuki (rotary cutting thin sheets) and sengiri (cutting thin strips from those sheets). There is edo-usuba (square tip) and kamagata-usuba (round tip). General sizes are 180 mm to 240 mm.

- Kiritsuke: hybrid with the length of yanagiba and the blade height and profile of usuba with an angled tip as a compromise. Requires great knife control because of the height, length, and flatness. General size is 240 mm to 300 mm.

- Mukimono: Used along with usuba for vegetables. It has an angled tip for decorative vegetable cutting. General size is 150 mm to 210 mm.

- Hamokiri: (literally pike conger cutter). It is a knife intermediate in thickness and length between deba and yanagiba to cut the thin bones and flesh of pike conger. General size is 240 mm to 300 mm.

- Magurokiri: (literally tuna knife). It is used to cut perpendicular (shorter) or parallel (longer and more flexible) to the tuna and is sized accordingly. Sizes range from 400 mm to 1500 mm.

- Honesuki: Used to debone chicken. A thicker version called garasuki is used to cut through bones. Most have an angled tip to slip between tendons and cut them. General size is 135 mm to 180 mm.

- Sobakiri: (literally soba cutter). A variant is udonkiri (udon cutter). General size is 210 mm to 300 mm.

- Unagisaki: Eel knife. Comes in variants from Kanto, Kyoto, Nagoya, and Kyushu.

Steel

Defining characteristics of Japanese kitchen knives are toughness (resistance to breaking), sharpness (smallest carbide and grain for smallest apex reduce force in cutting), edge life (an index for the length of time an edge will cut based on lack of edge rolling or chipping), edge quality (toothy with large carbides or refined with small carbides), and ease of sharpening (steel easily abrades in stone and forms a sharp edge). Although each steel has its own chemical and structural limits and characteristics, the heat treatment and processing can bring out traits both inherent to the steel and like its opposite counterparts.

Stainless steel is generally tougher, less likely to chip, and less sharp than carbon. At the highest end, they retain an edge longer and are similarly sized in carbides to carbon steel. Variants include:

- Powdered steel which has large carbides broken up by powdering process and sintered together under high pressure and temperature.

- Semi stainless which has a less chromium-free to prevent rust of the iron and intermediate properties between carbon and stainless.

- Tool steel which is heavily alloyed and may or may not be stainless.

Carbon steel is generally sharper, harder, more brittle, less tough, easier to sharpen, and more corrosive.

- White steel: purified from phosphorus and sulfur and unalloyed. Comes in variants 1, 2, and 3 (from higher to lower carbon).

- Blue steel: purified and alloyed with chromium and tungsten for edge life and toughness. Comes in variants 1, 2.

- Super blue steel: blue steel alloyed with molybdenum and vanadium and more carbon for longer edge life but a little more brittle.

Construction

Monosteel blades are usually harder to sharpen and thinner than laminated blades. 3 Kinds of monosteel blades are:

- Zenko – stamped out;

- Honyaki – forged down from carbon steel with differential hardening;

- Forged down from a billet without differential hardening

Laminated blades come in 3 different types: awase (meaning mixed, for mixed steel), kasumi (meaning misty, referring to the misty look of iron after sharpening), and hon-kasumi (higher quality kasumi). Forming a laminated blade involves 2 pieces of steel, the jigane and the hagane. The jigane refers to soft cladding, or skin, and hagane refers to hard cutting steel. Both commonly contain carbon or stainless steel. This combination of metals makes laminated blades corrosion-resistant with the stainless steel, and strong with carbon. Constructions like stainless clad over a carbon core are less common because of the manufacture difficulty. The jigane allows the knife to be sharpened more easily and absorb shock. It also makes the hagane harder without making the whole blade fragile. The two forms of laminated blades are:

- Ni-mai – jigane with hagane;

- San-mai – hagane sandwiched between jigane

A variation on the traditional laminated blade style is to form an artistic pattern in the jigane. Patterns include:

- Suminagashi;

- Damascus;

- Kitaeji;

- Mokume-gane;

- Watetsu

Production

A great deal of high-quality Japanese cutlery originates from Sakai, the capital of samurai sword manufacturing since the 14th century. After the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the samurai were banned from carrying swords as part of an attempt to modernize Japan. Though a demand for military swords remained and some sword-smiths still produced traditional samurai swords as art, the majority of sword-smiths refocused their skill to cutlery production, following the cultural shift.

The production of steel knives in Sakai began in the 16th century, when tobacco was introduced to Japan by the Portuguese and Sakai craftsmen started to make knives for cutting tobacco. The Sakai knife industry received a major boost from the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868), which granted Sakai a special seal of approval and enhanced its reputation for quality.

Today, Seki, Gifu is considered the home of modern Japanese kitchen cutlery, where state-of-the-art manufacturing technology has updated ancient forging skills to produce a world-class series of stainless and laminated steel kitchen knives. Many major cutlery-making companies are based in Seki, producing the highest-quality kitchen knives in both the traditional Japanese style and western styles, such as the gyuto and the santoku. Knives and swords are so integral to the city that it is home to the Seki Cutlery Association, the Seki Swordsmith Museum, the Seki Outdoor Knife Show, the October Cutlery Festival, and the Cutlery Hall. Most manufacturers are small family businesses where craftsmanship is more important than volume, and they typically produce fewer than a dozen knives per day.[9]

Design and use

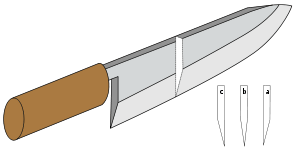

Unlike western knives, Japanese knives are often only single ground, meaning that they are sharpened so that only one side holds the cutting edge. As shown in the image, some Japanese knives are angled from both sides, while others are angled only from one side with the other side of the blade being flat. It was traditionally believed that a single-angled blade cuts better and makes cleaner cuts, though requiring more skill to use than a blade with a double-beveled edge. Generally, the right-hand side of the blade is angled, as most people use the knife with their right hand. Left-handed models are rare and must be specially ordered and custom made.[9]

Since the end of World War II, western-style, double-beveled knives have gained popularity in Japan. One example of this transition is the santoku, an adaptation of gyoto. Other knives that have become widely used in Japan are the French chef's knife and the sujihiki, roughly analogous to a western carving knife. While these knives are usually sharpened symmetrically on both sides, their blades are still given Japanese-style acute-angle cutting edges of 8-10 degrees per side with a very hard temper to increase cutting ability.

Most professional Japanese cooks own their personal set of knives. After sharpening a carbon-steel knife in the evening after use, the user may let the knife "rest" for a day to restore its patina and remove any metallic odor or taste that might otherwise be passed on to the food.[10] Some cooks choose to own two sets of knives for this reason.

Japanese knives feature subtle variations on the chisel grind. Usually, the back side of the blade is concave to reduce drag and adhesion so the food separates more cleanly (this feature is known as urasuki[11]). The kanisaki deba, used for cutting crab and other shellfish, has the grind on the opposite side (left side angled for right-handed use), so that the meat is not cut when chopping the shell.[12]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japanese kitchen knives. |

Notes

- Itoh, Makiko (2017-05-27). "Hone your knowledge of Japanese kitchen knives". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- Shackleford, Steve (2010-09-07). Spirit Of The Sword: A Celebration of Artistry and Craftsmanship. Krause Publications. ISBN 1440216398.

- "5 Best Japanese Knives Reviews - Updated 2019 (A Must Read!)". Village Bakery. 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- Carter, Murray (2011-09-22). Bladesmithing with Murray Carter: Modern Application of Traditional Techniques. Krause Publications. ISBN 1440218471.

- "Gyutos". Chef Knives To Go. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Bonem, Max (1 July 2009). "Japanese Knife Guide". Food & Wine Magazine. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "Santokus". Chef Knives To Go. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "Nakiris". Chef Knives To Go. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Hurt, Harry, III (2006) "How to Succeed at Knife-Sharpening Without Losing a Thumb" The New York Times, September 23, 2006. Accessed September 23, 2006.

- Shizuo Tsuji (1980). Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art. Kodansha International Limited. ISBN 978-0-87011-399-4.

- Knife Edge Grind Types

- Japanese Kitchen Knife Types And Styles

References

- Tsuji, Shizuo, and Mary Sutherland. Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, first edition. Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd., 1980. ISBN 0-87011-399-2.

Further reading

- Nozaki, Hiromitsu, & Klippensteen, Kate (2009) Japanese Kitchen Knives: essential techniques and recipes. Tokyo: Kodansha International ISBN 978-4-7700-3076-4

- Tsuji, Shizuo, & Sutherland, Mary (2006) Japanese Cooking: a simple art; revised edition. Tokyo: Kodansha International ISBN 978-4-7700-3049-8