Gwalia, Western Australia

Gwalia is a former gold-mining town located 233 kilometres north of Kalgoorlie and 828 kilometres east of Perth in Western Australia's Great Victoria Desert. Today, Gwalia is essentially a ghost town, having been largely deserted since the main source of employment, the Sons of Gwalia gold mine, closed in 1963.[1] Just four kilometres north is the town of Leonora, which remains the hub for the area's mining and pastoral industries.

| Gwalia Western Australia | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The State Hotel, Gwalia, built 1903, in 2018 | |

Gwalia | |

| Coordinates | 28°54′48″S 121°19′47″E |

| Established | 1897 |

| Postcode(s) | 6438 |

| Elevation | 377 m (1,237 ft) |

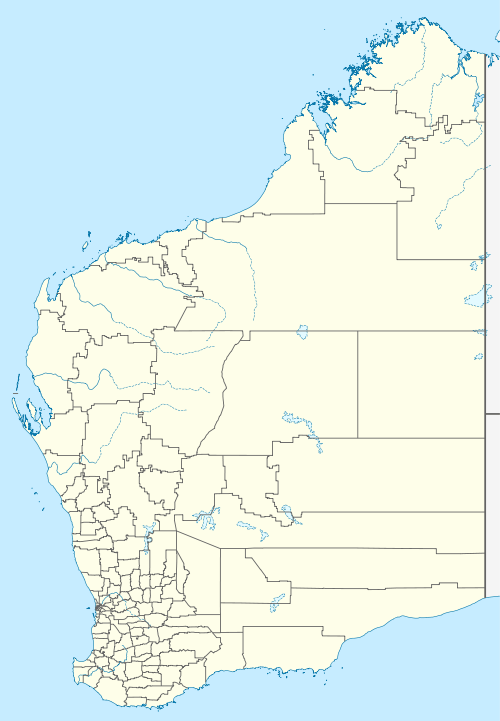

| Location |

|

| LGA(s) | Shire of Leonora |

History

The Wongatha people are the traditional owners and inhabitants of Gwalia.

Underground mining at the Sons of Gwalia began in 1897, and continued until 1963. During this time it produced 2.644 million ounces (82.24 tonnes) of gold down to a depth of 1,080 metres (3,543 ft) via an incline shaft.[2] Sons of Gwalia grew to become the largest Western Australian gold mine outside Kalgoorlie, and the deepest of its kind in Australia. The 2.644 million ounces recovered (1897–1963) amounts in value to US$4.34 billion (A$4.55 billion) at August 2012 prices.

The area where Leonora-Gwalia are situated was first travelled by Sir John Forrest in 1869 during an unsuccessful search for signs of explorer Ludwig Leichhardt's expedition from the east. Forrest named a noticeable knoll Mount Leonora after a female relative. A number of years passed before Edward "Doodah" Sullivan first pegged the area in 1896 for gold prospecting, on the heels of recent finds in Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie. Gold was discovered near the base of Mount Leonora in May 1896 by Carlson, White and Glendinning, who named the claim "Sons of Gwalia" in honour of Thomas Tobias, a storekeeper in Coolgardie, who funded them. The name Gwalia, the ancient name for the country of Wales, was chosen because of Tobias' Welsh heritage. They then sold their claim for £5,000 to George Hall, who in turn recouped his investment in about one month.

Hall sought additional capital, and began negotiations with a London firm, Bewick, Moreing & Co. They in turn sent a young American geologist to the area to develop the find into a working concern. That geologist was Herbert Hoover, who would later become President of the United States.[3] Hoover arrived in Albany, Western Australia in May 1897, travelled by train to Coolgardie, then eventually to the Gwalia area by camel. He suggested himself as manager of the new mine. Among his suggestions for cutting labour costs was to hire mostly Italian labourers. As a result, the town's population was made up mostly of Italian immigrants, as well as other Europeans, who sought riches in Australia's newest gold rush.

Hoover's stay in Gwalia was brief; he was sent to China in December 1898 to develop mines there. The house that Hoover lived in, overlooking the mine operations, still exists, and today operates as a museum and bed-and-breakfast inn. Hoover returned to Western Australia and Gwalia in 1902 as a partner in Bewick Moreing and manager of all of their interests in Western Australia.[4]

As the mine developed, workers camped out nearby, building shanties of corrugated iron and hessian cloth, some with dirt floors. The town of Gwalia was born. Meanwhile, an area to the north was being surveyed, which became the town of Leonora. Leonora was formally established in 1898, and the two towns developed a certain rivalry. This was eased when a steam tramway was built linking the two towns (1903), adding to the rail link from Kalgoorlie built the year before. It was the first such tramway built in Western Australia. It was replaced by an electric tram in 1907.[5] An electricity generating station was established in 1902 to provide power to the mines. It was fired by mulga timber gathered from surrounding areas and a number of 2-foot gauge tramways were laid to enable haulage.[5] Gwalia also became home to the state's first public swimming pool, and the first State Hotel (1903). While the pool saw abandonment along with the rest of the town when the mine closed, the hotel remained occupied by various tenants, and stands today as a popular attraction.

As the mine grew, so did the town's population. In 1901, Gwalia hosted 884 residents, while Leonora had 314. By 1910, Leonora had grown to 1,154, and Gwalia to an overall peak of 1,114. A major slump hit the area in 1921 following a fire at the mine; the damage caused mining to stop for three years. The resulting downturn cut the population in both towns by half. The area slowly grew afterward, but never achieved earlier population numbers while the mine was in operation. By the early 1960s, gold resources in the Sons of Gwalia were taxing existing techniques and profitability, and in December 1963, Bewick & Moreing closed the mine. The town's population disappeared almost overnight.[6][7] By 1966, the combined population of Leonora and Gwalia was only 338, the majority living in Leonora.

Leonora remained a pastoral hub and home to the Shire of Leonora's administration, but Gwalia fell into disrepair, with just a few residents remaining behind. However, both the town and mine gradually became popular tourist attractions.

Around 1969 nickel was discovered in the area, prompting new growth. Leonora's population grew slowly during the 1970s, but Gwalia remained stagnant and deteriorating. A historical preservation effort began in 1971 to restore and preserve the town's remaining homes and buildings, as well as the mine's original structures (headframe and winder building).

The 1980s saw the Sons of Gwalia reopen under a new scheme to tap underground resources using more modern and efficient extraction methods. A superpit cut into the original workings, requiring the headframe and winder building be moved. The new operation, which promised an additional 1.6 million ounces of gold, was traded on the Australian Stock Exchange and saw significant growth. The new mine eventually produced 2.4 million ounces of gold at an average of 5.2 grams per ton, the same amount as the old mine but in a third of the time.

Gwalia made national news in 2000 when a chartered plane carrying seven Sons of Gwalia workers (plus the pilot) crashed.[8] The plane, a twin-engine Beechcraft Super King Air 200, apparently lost cabin pressure shortly after takeoff from Perth. The pilot and passengers were left without enough oxygen, and the plane continued in a straight line on autopilot until it ran out of fuel and crashed in Queensland, 2,840 kilometres from Perth. The incident mirrored the tragedy in the United States that claimed golfer Payne Stewart only months earlier.

Sons of Gwalia NL found itself in financial difficulty in 2004 (through hedging), and the resulting crash became headline news across the country and sent waves throughout the world's gold trading market. The mine saw a resurgence in the late 2000s, with St Barbara Limited developing a deeper decline. Targets are around 2,000 m underground, with gold production beginning when they reach 1,100 m. As of April 2008 the decline is at around 1,000 vertical metres below the surface, with a portal from the old pit. This is a continuation of where Sons of Gwalia left off, at around 375 vertical metres down.

References

- Gwalia Museum Homepage

- Porter, T.M. (2006). "Sons of Gwalia, Gwalia, Tower Hill". Porter GeoConsultancy Pty Ltd. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "Stanford University article on Herbert Hoover's time in Australia". Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2005.

- Watson, J. Director, Gwalia Historic Site

- Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, June, 1964 pp 106-112

- Lucas, Jarrod (9 June 2017). "Outback WA ghost town of Gwalia to live on thanks to multi-million dollar preservation effort". ABC News. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Stevens, Rhiannon (20 November 2018). "Gwalia was frozen in time when residents abandoned it one afternoon. Now, there's new life". ABC News. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Eight Killed In Australia Plane Crash