Guy Anderson

Guy Anderson (November 20, 1906 – April 30, 1998) was an American artist known primarily for his oil painting who lived most of his life in the Puget Sound region of the United States. His work is in the collections of numerous museums including the Seattle Art Museum, the Tacoma Art Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He has been called "Perhaps the most powerful artist to emerge from the Northwest School".[1]

Guy Anderson | |

|---|---|

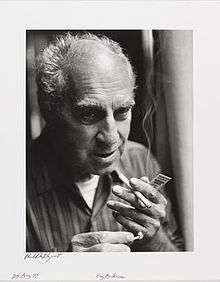

Guy Anderson, 1987. Photo: Paul Dahlquist. Collection of the Portland Art Museum. | |

| Born | November 20, 1906 |

| Died | April 30, 1998 (aged 91) Mount Vernon, Washington |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Northwest School |

| Awards | 1975 Guggenheim Fellowship 1995 Bumbershoot Golden Umbrella Lifetime Achievement |

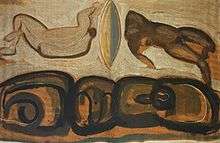

Anderson's mature work often draws from a set of symbols (circle, spiral, egg, seed, wave) he developed from the study of religious, mythical, and philosophical sources.[1] The symbols are frequently combined with the human figure. Beginning in 1960s he painted on brown roofing paper that came in long rolls and permitted him to paint on a grand scale.[2]

Anderson said: "I read the Vedanta and the Vedas and I think about the order of the universe. The more we send men out into space, the more I realize we already are in space, floating out there. The whole order is preordained, in some miraculous way. I think all creation is magical."[3]

Early life

Anderson grew up in a semi-rural setting north of Seattle, in the town of Edmonds, Washington, where he'd been born on November 20, 1906. Some of his early paintings portrayed his family home. A piano was an important presence in his house. His father, Irving Anderson, was a carpenter-builder and also a musician. From an early age Guy was intrigued by other cultures; he was particularly fascinated by the woodcarvings of Northern Coastal native tribes, and by the collection of Japanese prints owned by his piano teacher. As soon as he was old enough to do so on his own, he began commuting to the Seattle Public Library by bus to study art books.[2][4]

After graduating from Edmonds High School, Anderson briefly studied with Alaskan scenic painter Eustace Ziegler, who encouraged Anderson's career-long preference for oil paints, and taught him how to draw nude figures, which would become important features of his work.[2][4]

In 1929, Anderson applied for and won a Tiffany Foundation scholarship and spent the summer studying at the Tiffany estate on Long Island, New York. As there were no art museums in Seattle at that time, he delighted in weekend visits to the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, examining the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Whistler, and many others.[2]

Career

On his return to Washington in the fall of 1929, Anderson set up a studio in an outbuilding on his parents' property, and had paintings included in a group show at the Fifth Avenue Gallery in downtown Seattle. The show piqued the interest of 19-year-old painter Morris Graves, who lived near Anderson, and the two became lifelong friends. In 1934 they traveled together to California in a beat-up panel truck, attempting to sell their paintings along the way. They also spent time painting near Monte Cristo in the North Cascade mountains.

With the opening of the Seattle Art Museum in 1933, Anderson befriended its founder, Dr. Richard Eugene Fuller, and worked there for several years, off-and-on, as an installer and children's art teacher. His lifelong interest in Asian art and culture was deepened by both close exposure to the museum's major collection of Asian art and artefacts, and by socializing and sometimes painting with members of Seattle's vibrant Asian arts community.[5] In the Northwest Annual Exhibition of 1935 he won the Katherine Baker Purchase Award, and the museum mounted a solo exhibition of his work the following year.[2]

In 1937, Anderson helped refurbish a burned-out house Morris Graves had discovered near the small town of La Conner, Washington, in the Skagit Valley, about sixty miles north of Seattle. The two decorated the earthen-floored studio with furniture made of driftwood and raw cedar logs.[2]

Like many artists during the Great Depression, Anderson worked for the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project. Hired by the program's Washington director, R. Bruce Inverarity, he taught at the Spokane Art Center in 1939-40, alongside painters Carl Morris and Clyfford Still, sculptor Hilda Deutsch, and muralist Ruth Egri. The center was widely praised as being among the most popular and productive of the more than 100 community art centers opened nationwide by the FAP.[6]

Throughout the 1940s and 50s Anderson was very much involved in Seattle's bustling art community. Morris Graves and Mark Tobey had become artists of international reputation; Tobey's studio and the home of painters Margaret and Kenneth Callahan become centers of lively socializing and philosophical debate. Otto Seligman and Zoe Dusanne were championing abstract art at their respective galleries, while SAM, the Henry Art Gallery, and the Frye Art Museum cautiously supported it. Anderson taught at the Helen Bush School in Seattle and Ruth Pennington's Fidalgo Art School in La Conner, while working at SAM, building stone mosaic patios for well-to-do patrons, and producing driftwood art for the commercial market. He lived in Seattle's University District, but spent much of his time painting at Graves' studio in La Conner or at the Callahans' summer place in Granite Falls, Washington. After a very successful show at SAM in 1945, he purchased his own cabin in Granite Falls. In September 1953 he became nationally known when Life magazine ran a major feature presenting Anderson, Tobey, Graves, and Kenneth Callahan as the "big four" of Northwest mystic art.[2]

In 1959 Anderson left Seattle for good. He rented a house on the edge of La Conner, where he found inspiration from the vast skies and natural settings of the surrounding area. He gathered rocks and driftwood, which he composed around his rustic home in various assemblages. For a time, he rented a studio on the main street of La Conner. Later, he bought property at 415 Caledonia Street, building a house and studio there. He began painting large works on roofing paper purchased from a local lumber company. Working with large sheets of paper on the floor in the studio above his living room, Anderson used thinned oil paint and large brushes. The scale of the format enabled his brushstrokes to become expansive and expressive, while its texture gave unexpected complexities which he valued.

Over the years his art ranged from densely worked and tightly composed figurative images of Northwest landscapes to large, sweeping brushstrokes with flowing, symbolic and iconographic forms. Anderson always preferred a limited palette of mostly muted earthy tones, sometimes accented with brilliant red. The male nude—often placed horizontally—figures prominently in many of his paintings. His works are often inspired by, and titled after, Greek mythology and Native American iconography.

In 1966 Anderson traveled to Europe for the first time with friends and fellow artists Clayton and Barbara James. In 1975 he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which, among other things, allowed him to visit major museums in Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., and travel extensively in Mexico. In 1982 he visited Osaka, Japan for an exhibition featuring his work.[2] He received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Seattle Center in 1995, and many who knew him personally considered him a "living treasure." Anderson was a complex, affable, and generous man with a wide-ranging mind and a devious sense of humor. His paintings can be read in many ways, but he cherished the premise of the human figure—a prominent feature in many of his works—as being symbolic of the journey of life.

Final years

Guy Anderson never quite achieved the international stature of his friends Tobey and Graves. This was partly due to bad luck - such as a newspaper strike leaving his first solo exhibition in New York (at the Smolin Gallery in 1962) unreviewed - but he turned down other important exhibition opportunities, including one at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, simply because he felt he didn't have enough material of sufficient quality ready.[2] He remained a pre-eminent artist with strong sales and major commissioned projects in the Pacific Northwest. His expressions of northwest atmospheres with their mythological allusions are distinctive, even as they evoke the coastal Skagit River country where he lived.

In the 1980s, with his health declining, Anderson arranged to be cared for as an elder, and he became increasingly dependent on a younger companion, Deryl Walls. Walls eventually became executor of his estate, and made the controversial decision to end Anderson's long association with Francine Seders, who had been his agent since 1966.[7] Anderson continued living in the house he had built on Caledonia Street, where he received visitors and continued painting into his late eighties. Walls eventually moved Anderson into his own home on Maple Street in La Conner, where Anderson was cared for while surrounded by his paintings. Walls hosted birthday parties for Anderson which were well attended by collectors, fellow artists, and admirers. He remained lucid and enjoyed visitors at La Conner until shortly before he died on April 30, 1998, aged 91 years.[8]

Legacy

Anderson's work has been included in exhibitions at the Seattle Art Museum, the Henry Art Gallery, the Bellevue Arts Museum, the Tacoma Art Museum, the Museum of Northwest Art in La Conner, the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington, and the National Museum of Art in Osaka Japan.[9] In 2014, several of his works were included in Modernism in the Pacific Northwest: the Mythic and the Mystical, a major exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum.[10]

References

- Anderson, Guy, 1906-1998.; Guenther, Bruce (1986). Guy Anderson. Francine Seders Gallery (Seattle, Wash.). Seattle, Wash.: Francine Seders Gallery. pp. 98, 104. ISBN 0-295-96419-7. OCLC 14989754.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ament, Deloris Tarzan; Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art, University of Washington Press, 2002; ISBN 0295981474

- "The Seattle Times". July 11, 1982. p. 82.

- Wehr, Wesley, The Eighth Lively Art: Conversations with Painters, Poets, Musicians, and the Wicked Witch of the West; University of Washington Press, 2000; ISBN 029580257X

- Hallmark, Kara Kelley; Encyclopedia of Asian American Artists: Artists of the American Mosaic. Greenwood, 2007; ISBN 031333451X

- Mahoney, Eleanor, The Spokane Arts Center: Bringing Art to the People; Pacific Northwest Labor & Civil Rights/University of Washington website; retvd 6 24 14; http://depts.washington.edu/depress/spokane_art_center.shtml

- Farr, Sheila. "Seders, Francine (b. 1932)"; HistoryLink.org Essay 10675 http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?displaypage=output.cfm&file_id=10675 retvd 6 25 14

- Updike, Robin (May 2, 1998). "Guy Anderson embodied Northwest point of view; painter who rarely left his home state dies at 91". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Woodside/Braseth Gallery, artist biography http://www.woodsidebrasethgallery.com/artists/guy-anderson/ retvd 6 25 14

- Upchurch, Michael. "A fresh look back at ‘Modernism in the Pacific Northwest’ ", the Seattle Times, June 18, 2014

Bibliography

- Conkelton, Sheryl, What It Meant to be Modern: Seattle Art at Mid-Century, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle 1999

- Conkelton, Sheryl, and Landau, Laura, Northwest Mythologies: The Interactions of Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson, Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma WA; University of Washington Press, Seattle and London 2003

- Kingsbury, Martha, Art of the Thirties: The Pacific Northwest, University of Washington Press for Henry Art Gallery, Seattle and London 1972

- Wehr, Wesley, " The Accidental Collector " University of Washington Press

- Wehr, Wesley, "The Eighth Lively Art " University of Washington Press

External links

- Guy Anderson collection of the Tacoma Art Museum. Over 25 of Anderson's works ranging from the 1950s to the 1980s.

- Guy Anderson collection of Henry Art Gallery. Over 25 works ranging from 1940 to the late 1970s.

- Guy Anderson collection of the Portland Art Museum. Contains about a dozen works.

- University of Washington Digital Collections. Includes photographs of Anderson in his studio.

- 1983 interview of Guy Anderson. Conducted for the Archives of American Art's Northwest Oral History Project.