Gu-Edin

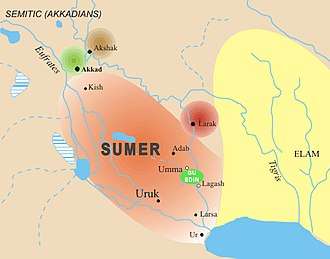

Gu-Edin (also transcribed "Gu'edena" or "Guedena") was a fertile plain in Sumer, in modern-day Iraq. It lay between Umma and Lagash, and claims made on it by each side were a cause of war.[1] Argument over the territory continued for around 150 years.[2]

Early history

According to a peace between Umma and Lagash mediated by Mesilim, king of Kish had determined where the boundary lay and the terms of use of a canal used to irrigate the land. The terms of that agreement were recorded on a stone monument called a stele, but Umma continued to feel that Lagash were unfairly advantaged by it.[2]

Reign of Eannatum

It is recorded on the Stele of the Vultures that Gu-Edin was pillaged by a later (énsi) of Umma, who ruled that city on behalf of its god Shara, and whose name, according to the Cone of Enmetena,[lower-alpha 1] was Ush. Gu-Edin had been claimed by the énsi of Lagash, Eannatum – author of the Stele of Vultures – as the property of Lagash's god, Ninĝirsu, and the pillaging precipitated a war between the two cities.[7]

Eannatum attacked back and Umma was heavily defeated.[2][8] By the time peace was re-established, Ush was either dead or deposed.

Treaty

A peace treaty was agreed between his successor, Enakalli, and Eannatum which established Gu-Edin as the property of Ninĝirsu.[8] A deep canal was dug to mark the freshly agreed border and two stone monuments were put in place: the Stele of Mesilim, which had been there before, and a newly carved one.[8] Leonard William King, writing in 1910, suggested that the second stele may have had much the same text as the Stele of the Vultures, but that the latter would not have been on the boundary itself.[9]

The treaty, which was sealed with oaths and the erection of temples, also included the establishment of an 'ownerless' tract of land intended as a buffer, and treated any barley Umma grew in that area of Gu-Edin to which it had access as a loan from Lagash, with resulting interest.[10][2] That area of land, then, could be used by Umma but only by paying rent. However, Umma did not reliably pay up.[10]

Later events

Gu-Edin was invaded by Umma at least twice during the reign of Eannatum's son, Entemena: once by Ur-Lumma and once by his successor Illi. The first attack was defeated soundly, according to Entemena's account, and the second was not lastingly successful.[5]

Lagash finally fell to Lugalzagesi, king of Umma, circa 2350 BCE, ending the First Dynasty of Lagash. Tablets of lamentation have been found, recording the fall of Lagash to Lugalzagesi, during the rule of Urukagina.[12] Lugalzagesi went on to conquer the whole of Sumer, until he was himself vanquished by Sargon of Akkad.

See also

Notes

References

- Lomazoff 2013.

- Flannery & Marcus, pp. 492–493.

- "Cone of Enmetena, king of Lagash". 2020.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- "Enmetena". Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. Oxford University. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "patesi". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- King 1994, pp. 120–123.

- King 1994, pp. 126–128.

- King 1994, pp. 142–143.

- Wilcke 2007, pp. 73–75.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

Sources

- King, Leonard W. (1994) [1st published 1910 by Chatto and Windus]. A History of Sumer and Akkad. Ripol Classic. ISBN 978-5-87664-034-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Flannery, Kent; Marcus, Joyce (2012). The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06497-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)</ref>

- Lomazoff, Amanda (2013). "Sumer". The Atlas of Military History. with Aaron Ralby. Thunder Bay Press. pp. 487–488. ISBN 978-1-60710-985-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilcke, Claus (2003). Early Ancient Near Eastern Law: A History of Its Beginnings: the Early Dynastic and Sargonic Periods. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-132-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Cone of Enmetena at The Louvre

- A War for Water—The Tale of Two City-States at ClassicalWisdom.com