Ninurta

Ninurta,[lower-alpha 1] also known as Ninĝirsu,[lower-alpha 2] is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with farming, healing, hunting, law, scribes, and war who was first worshipped in early Sumer. In the earliest records, he is a god of agriculture and healing, who releases humans from sickness and the power of demons. In later times, as Mesopotamia grew more militarized, he became a warrior deity, though he retained many of his earlier agricultural attributes. He was regarded as the son of the chief god Enlil and his main cult center in Sumer was the Eshumesha temple in Nippur. Ninĝirsu was honored by King Gudea of Lagash (ruled 2144–2124 BC), who rebuilt Ninĝirsu's temple in Lagash.

| Ninurta | |

|---|---|

God of agriculture, hunting, and war | |

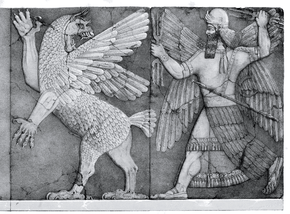

Assyrian stone relief from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu, showing the god with his thunderbolts pursuing Anzû, who has stolen the Tablet of Destinies from Enlil's sanctuary[1] (Austen Henry Layard Monuments of Nineveh, 2nd Series, 1853) | |

| Abode | Eshumesha temple in Nippur Later Kalhu, during Assyrian times |

| Planet | Saturn |

| Symbol | Plow and perched bird |

| Mount | Sometimes shown riding a beast with the body of a lion and the tail of a scorpion |

| Parents | Usually Enlil and Ninhursag, but sometimes Enlil and Ninlil |

| Consort | As Ninurta: Gula As Ninĝirsu: Bau |

Later, Ninurta became beloved by the Assyrians as a formidable warrior. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) built a massive temple for him at Kalhu, which became his most important cult center from then on. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Ninurta's statues were torn down and his temples abandoned because he had become too closely associated with the Assyrian regime, which many conquered peoples saw as tyrannical and oppressive.

In the epic poem Lugal-e, Ninurta slays the demon Asag using his talking mace Sharur and uses stones to build the Tigris and Euphrates rivers to make them useful for irrigation. In a poem sometimes referred to as the "Sumerian Georgica", Ninurta provides agricultural advice to farmers. In an Akkadian myth, he was the champion of the gods against the Anzû bird after it stole the Tablet of Destinies from his father Enlil and, in a myth that is alluded to in many works but never fully preserved, he killed a group of warriors known as the "Slain Heroes". His major symbols were a perched bird and a plow.

Ninurta may have been the inspiration for the figure of Nimrod, a "mighty hunter" who is mentioned in association with Kalhu in the Book of Genesis. He may also be mentioned in the Second Book of Kings under the name Nisroch.[lower-alpha 3] In the nineteenth century, Assyrian stone reliefs of winged, eagle-headed figures from the temple of Ninurta at Kalhu were commonly, but erroneously, identified as "Nisrochs" and they appear in works of fantasy literature from the time period.

Worship

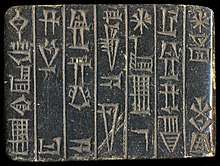

Ninurta was worshipped in Mesopotamia as early as the middle of the third millennium BC by the ancient Sumerians,[5] and is one of the earliest attested deities in the region.[5][1] His main cult center was the Eshumesha temple in the Sumerian city-state of Nippur,[5][1][6] where he was worshipped as the god of agriculture and the son of the chief-god Enlil.[5][1][6] Though they may have originally been separate deities,[1] in historical times, the god Ninĝirsu, who was worshipped in the Sumerian city-state of Girsu, was always identified as a local form of Ninurta.[1] According to the Assyriologists Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, the two gods' personalities are "closely intertwined".[1] King Gudea of Lagash (ruled 2144–2124 BC) dedicated himself to Ninĝirsu[3] and the Gudea cylinders, dating to c. 2125 BC, record how he rebuilt the temple of Ninĝirsu in Lagash as the result of a dream in which he was instructed to do so.[3][7] The Gudea cylinders record the longest surviving account written in the Sumerian language known to date.[3] Gudea's son Ur-Ninĝirsu incorporated Ninĝirsu's name as part of his own in order to honor him.[3] As the city-state of Girsu declined in importance, Ninĝirsu became increasingly known as "Ninurta".[2] Though Ninurta was originally worshipped solely as a god of agriculture,[3] in later times, as Mesopotamia became more urban and militarized, he began to be increasingly seen as a warrior deity instead.[3] He became primarily characterized by the aggressive, warlike aspect of his nature.[3][1] In spite of this, however, he continued to be seen as a healer and protector,[3] and he was commonly invoked in spells to protect against demons, disease, and other dangers.[3]

In later times, Ninurta's reputation as a fierce warrior made him immensely popular among the Assyrians.[5][8][3] In the late second millennium BC, Assyrian kings frequently held names which included the name of Ninurta,[5][3] such as Tukulti-Ninurta ("the trusted one of Ninurta"), Ninurta-apal-Ekur ("Ninurta is the heir of [Ellil's temple] Ekur"), and Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur ("Ninurta is the god Aššur's trusted one").[5] Tukulti-Ninurta I (ruled 1243–1207 BC) declares in one inscription that he hunts "at the command of the god Ninurta, who loves me."[5][3] Similarly, Adad-nirari II (ruled 911–891 BC) claimed Ninurta and Aššur as supporters of his reign,[5] declaring his destruction of their enemies as moral justification for his right to rule.[5] In the ninth century BC, when Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) moved the capital of the Assyrian Empire to Kalhu,[5] the first temple he built there was one dedicated to Ninurta.[5][9][8][10]

The walls of the temple were decorated with stone relief carvings,[5][8][3] including one of Ninurta slaying the Anzû bird.[11][5][3][12] Ashurnasirpal II's son Shalmaneser III (ruled 859–824 BC) completed Ninurta's ziggurat at Kalhu and dedicated a stone relief of himself to the god.[5][3] On the carving, Shalmaneser III's boasts of his military exploits[5] and credits all his victories to Ninurta, declaring that, without Ninurta's aid, none of them would have been possible.[5] When Adad-nirari III (ruled 811–783 BC) dedicated a new endowment to the temple of Aššur in Assur, they were sealed with both the seal of Aššur and the seal of Ninurta.[5] Assyrian stone reliefs from the Kalhu period show Aššur as a winged disc, with Ninurta's name written beneath it, indicating the two were seen as near-equals.[3]

After the capital of Assyria was moved away from Kalhu, Ninurta's importance in the pantheon began to decline.[5][3] Sargon II favored Nabu, the god of scribes, over Ninurta.[5] Nonetheless, Ninurta still remained an important deity.[5][3] Even after the kings of Assyria left Kalhu, the inhabitants of the former capital continued to venerate Ninurta,[5][3] who they called "Ninurta residing in Kalhu".[5] Legal documents from the city record that those who violated their oaths were required to "place two minas of silver and one mina of gold in the lap of Ninurta residing in Kalhu."[5] The last attested example of this clause dates to 669 BC, the last year of the reign of King Esarhaddon (ruled 681 – 669 BC).[5] The temple of Ninurta at Kalhu flourished until the end of the Assyrian Empire,[5] hiring the poor and destitute as employees.[5][3] The main cultic personnel were a šangû-priest and a chief singer, who were supported by a cook, a steward, and a porter.[5] In the late seventh century BC, the temple staff witnessed legal documents, along with the staff of the temple of Nabu at Ezida.[5] The two temples shared a qēpu-official.[5]

Iconography

In artistic representations, Ninurta is shown as a warrior, carrying a bow and arrow and clutching Sharur, his magic talking mace.[3] He sometimes has a set of wings, raised upright, ready to attack.[3] In Babylonian art, he is often shown standing on the back of or riding a beast with the body of a lion and the tail of a scorpion.[3] Ninurta remained closely associated with agricultural symbolism as late as the middle of the second millennium BC.[3] On kudurrus from the Kassite Period (c. 1600 — c. 1155 BC), a plough is captioned as a symbol of Ninĝirsu.[1] The plough also appears in Neo-Assyrian art, possibly as a symbol of Ninurta.[1] A perched bird is also used as a symbol of Ninurta during the Neo-Assyrian Period.[11] One speculative hypothesis holds that the winged disc originally symbolized Ninurta during the ninth century BC,[8] but was later transferred to Aššur and the sun-god Shamash.[8] This idea is based on some early representations in which the god on the winged disc appears to have the tail of a bird.[8] Most scholars have rejected this suggestion as unfounded.[8] Astronomers of the eighth and seventh centuries BC identified Ninurta (or Pabilsaĝ) with the constellation Sagittarius.[13] Alternatively, others identified him with the star Sirius,[13] which was known in Akkadian as šukūdu, meaning "arrow".[13] The constellation of Canis Major, of which Sirius is the most visible star, was known as qaštu, meaning "bow", after the bow and arrow Ninurta was believed to carry.[13] In Babylonian times, Ninurta was associated with the planet Saturn.[14]

Family

Ninurta was believed to be the son of Enlil.[1] In Lugal-e, his mother is identified as the goddess Ninmah, whom he renames Ninhursag,[3][15] but, in Angim dimma, his mother is instead the goddess Ninlil.[16] Under the name Ninurta, his wife is usually the goddess Gula,[1] but, as Ninĝirsu, his wife is the goddess Bau.[1] Gula was the goddess of healing and medicine[17] and she was sometimes alternately said to be the wife of the god Pabilsaĝ or the minor vegetation god Abu.[17] Bau was worshipped "almost exclusively in Lagash"[18] and was sometimes alternately identified as the wife of the god Zababa.[18] She and Ninĝirsu were believed to have two sons: the gods Ig-alima and Šul-šagana.[18] Bau also had seven daughters, but Ninĝirsu was not claimed to be their father.[18] As the son of Enlil, Ninurta's siblings include: Nanna, Nergal, Ninazu,[19][20] Enbilulu,[21] and sometimes Inanna.[22][23]

Mythology

Lugal-e

Second only to the goddess Inanna, Ninurta probably appears in more myths than any other Mesopotamian deity.[24] In the Sumerian poem Lugal-e, also known as Ninurta's Exploits, a demon known as Asag has been causing sickness and poisoning the rivers.[15] Ninurta's talking mace Sharur urges him to battle Asag.[3] Ninurta confronts Asag, who is protected by an army of stone warriors.[8][5][25][3] Ninurta initially "flees like a bird",[3] but Sharur urges him to fight.[3] Ninurta slays Asag and his armies.[8][5][25][3] Then Ninurta organizes the world,[8][5] using the stones from the warriors he has defeated to build the mountains, which he designs so that the streams, lakes and rivers all flow into the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, making them useful for irrigation and agriculture.[8][3][15] Ninurta's mother Ninmah descends from Heaven to congratulate her son on his victory.[3][15] Ninurta dedicates the mountain of stone to her and renames her Ninhursag, meaning "Lady of the Mountain".[3][15] Nisaba, the goddess of scribes, appears and writes down Ninurta's victory, as well as Ninhursag's new name.[3] Finally, Ninurta returns home to Nippur, where he is celebrated as a hero.[5] This myth combines Ninurta's role as a warrior deity with his role as an agricultural deity.[8] The title Lugal-e means "O king!" and comes from the poem opening phrase in the original Sumerian.[5] Ninurta's Exploits is a modern title assigned to it by scholars.[5] The poem was eventually translated into Akkadian after Sumerian became regarded as too difficult to understand.[5]

A companion work to the Lugal-e is Angim dimma, or Ninurta's Return to Nippur,[5] which describes Ninurta's return to Nippur after slaying Asag.[5] It contains little narrative and is mostly a praise piece, describing Ninurta in larger-than-life terms and comparing him to the god An.[26][5] Angim dimma is believed to have originally been written in Sumerian during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC) or the early Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 – c. 1531 BC),[27] but the oldest surviving texts of it date to Old Babylonian Period.[27] Numerous later versions of the text have also survived.[27] It was translated into Akkadian during the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1600 — c. 1155 BC).[5][27]

Anzû myth

In the Old, Middle, and Late Babylonian myth of Anzû and the Tablet of Destinies, the Anzû is a giant, monstrous bird.[28][29][1] Enlil gives Anzû a position as the guardian of his sanctuary,[28][30] but Anzû betrays Enlil and steals the Tablet of Destinies,[31][32][1] a sacred clay tablet belonging to Enlil that grants him his authority,[33] while Enlil is preparing for his bath.[34][32] The rivers dry up and the gods are stripped of their powers.[30] The gods send Adad, Gerra, and Shara to defeat the Anzû,[30][34] but all of them fail.[30][34] Finally, the god Ea proposes that the gods should send Ninurta, Enlil's son.[30][34] Ninurta confronts the Anzû and shoots it with his arrows,[35][5][3] but the Tablet of Destinies has the power to reverse time[5][3] and the Anzû uses this power to make Ninurta's arrows fall apart in midair and revert to their original components:[35][5][3] the shafts turn back into canebrake, the feathers into live birds, and the arrowheads return to the quarry.[3] Even Ninurta's bow returns to the forest and the wool bowstring turns into a live sheep.[3]

Ninurta calls upon the south wind for aid, which rips the Anzû's wings off.[35][3] Ninurta slits the Anzû's throat and takes the Tablet of Destinies.[3] The god Dagan announces Ninurta's victory in the assembly of the gods[34] and, as a reward, Ninurta is a granted a prominent seat on the council.[34][30][13] Enlil sends the messenger god Birdu to request Ninurta to return the Tablet of Destinies.[36] Ninurta's reply to Birdu is fragmentary, but it is possible he may initially refuse to return the Tablet.[37] In the end, however, Ninurta does return the Tablet of Destinies to his father.[30][38][1][5] This story was particularly popular among scholars of the Assyrian royal court.[5]

The myth of Ninurta and the Turtle, recorded in UET 6/1 2, is a fragment of what was originally a much longer literary composition.[39] In it, after defeating the Anzû, Ninurta is honored by Enki in Eridu.[3][39] Ninurta has brought back a chicklet from the Anzû, for which Enki praises him.[3] Ninurta, however, hungry for power and even greater accolades, "set[s] his sights on the whole world.[3] Enki senses his thoughts and creates a giant turtle, which he releases behind Ninurta and which bites the hero's ankle.[3][39][40] As they struggle, the turtle digs a pit with its claws, which both of them fall into.[3][39][40] Enki gloats over Ninurta's defeat.[39][40] The end of the story is missing;[41][3] the last legible portion of the account is a lamentation from Ninurta's mother Ninmah, who seems to be considering finding a substitute for her son.[39] According to Charles Penglase, in this account, Enki is clearly intended as the hero and his successful foiling of Ninurta's plot to seize power for himself is intended as a demonstration of Enki's supreme wisdom and cunning.[39]

Other myths

In Ninurta's Journey to Eridu, Ninurta leaves the Ekur temple in Nippur and travels to the Abzu in Eridu, led by an unnamed guide.[42] In Eridu, Ninurta sits in assembly with the gods An and Enki[34] and Enki gives him the me for life.[43] The poem ends with Ninurta returning to Nippur.[43] The account probably deals with a journey in which Ninurta's cult statue was transported from one city to another and the "guide" is the person carrying the cult statue.[34] The story closely resembles the other Sumerian myth of Inanna and Enki, in which the goddess Inanna journeys to Eridu and receives the mes from Enki.[10] In a poem known as the "Sumerian Georgica", written sometime between 1700 and 1500 BC, Ninurta delivers detailed advice on agricultural matters,[1][44][3] including how to plant, tend, and harvest crops, how to prepare fields for planting, and even how to drive birds away from the crops.[1][3] The poem covers nearly every aspect of farm life throughout the course of the year.[1] Though the poem starts out seeming as though the advice is being given from a father to his son,[3] at the end, it concludes with the words: "These are the instructions of Ninurta, son of Enlil. O Ninurta, trustworthy farmer of Enlil, your praise is good."[3] The "father" at the beginning of the poem is thereby revealed to be Ninurta himself.[3]

The myth of the Slain Heroes is alluded to in many texts, but is never preserved in full.[1] In this myth, Ninurta must fight a variety of opponents.[45][3] Black and Green describe these opponents as "bizarre minor deities";[2] they include the six-headed Wild Ram, the Palm Tree King, and the seven-headed serpent.[3][13] Some of these foes are inanimate objects, such as the Magillum Boat, which carries the souls of the dead to the Underworld, and the strong copper, which represents a metal that was conceived as precious.[3][2] This story of successive trials and victories may have been the source for the Greek legend of the Twelve Labors of Heracles.[13][3]

Later influence

In antiquity

.jpg)

In the late seventh century BC, Kalhu was captured by foreign invaders.[5][3] Ninurta, like many other deities, had become inextricably associated with the Assyrian Empire, which was widely hated for what were perceived as cruel policies.[3] As a result, his statues were torn down[5][3] and his temples was abandoned and never restored, including his most famous one in Kalhu.[5][3] Despite this, Ninurta was never completely forgotten.[5][3] Most scholars agree that Ninurta was probably the inspiration for the biblical figure Nimrod, mentioned in Genesis 10:8–12 as a "mighty hunter".[46][44][48][49] Though it is still not entirely clear how the name Ninurta became Nimrod in Hebrew,[44] the two figures bear mostly the same functions and attributes[47] and Ninurta is currently regarded as the most plausible etymology for Nimrod's name.[44][5][3] The city of Kalhu is specifically referenced in association with Nimrod in Genesis 10:11–12, where it is described as a "great city".[3] Eventually, the ruins of the city of Kalhu itself became known in Arabic as Namrūd because of its association with Ninurta.[5][3]

Later in the Old Testament, in both 2 Kings 19:37 and Isaiah 37:38, King Sennacherib of Assyria is reported to have been murdered by his sons Adrammelech and Sharezer in the temple of "Nisroch",[49][5][8][13][48] which is most likely a scribal error for "Nimrod".[5][8][13][48] This hypothetical error would result from the Hebrew letter מ (mem) being replacing with ס (samekh) and the letter ד (dalet) being replaced with ך (kaf).[5][13] Due to the obvious visual similarities of the letters involved and the fact that no Assyrian deity by the name of "Nisroch" has ever been attested, most scholars consider this error to be the most likely explanation for the name.[5][13][48][50] If "Nisroch" is Ninurta, this would make Ninurta's temple at Kalhu the most likely location of Sennacherib's murder.[50] Other scholars have attempted to identify Nisroch as Nusku, the Assyrian god of fire.[49] Hans Wildberger rejects all suggested identifications as linguistically implausible.[49]

Although the Book of Genesis itself portrays Nimrod positively as the first king after the Flood of Noah and a builder of cities,[51] the Greek Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible refers to him as a giant[51] and mistranslates the Hebrew words meaning "before Yahweh" as "in opposition against God."[51] Because of this, Nimrod became envisioned as the archetypal idolator.[51] Early works of Jewish midrash, described by the first-century AD philosopher Philo in his Quaestiones, portrayed Nimrod as the instigator of the building of the Tower of Babel, who persecuted the Jewish patriarch Abraham for refusing to participate in the project.[51] Saint Augustine of Hippo refers to Nimrod in his book The City of God as "a deceiver, oppressor and destroyer of earth-born creatures."[51]

In modernity

_(8704834191).jpg)

In the sixteenth century, Nisroch became seen as a demon.[52][53][54] The Dutch demonologist Johann Weyer listed Nisroch in his Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (1577) as the "chief cook" of Hell.[53] Nisroch appears in Book VI of John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost (first published in 1667) as one of Satan's demons.[54][52] Nisroch, who is described as frowning and wearing beaten armor,[54] calls into question Satan's argument that the fight between the angels and demons is equal, objecting that they, as demons, can feel pain, which will break their morale.[54] According to Milton scholar Roy Flannagan, Milton may have chosen to portray Nisroch as timid because he had consulted the Hebrew dictionary of C. Stephanus, which defined the name "Nisroch" as "Flight" or "Delicate Temptation".[54]

In the 1840s, the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard uncovered numerous stone carvings of winged, eagle-headed genii at Kalhu.[5][8] Remembering the Biblical story of Sennacherib's murder, Layard mistakenly identified these figures as "Nisrochs".[5][8] Such carvings continued to be known as "Nisrochs" in popular literature throughout the remaining portion of the nineteenth century.[5][8] In Edith Nesbit's classic 1906 children's novel The Story of the Amulet, the child protagonists summon an eagle-headed "Nisroch" to guide them.[5] Nisroch opens a portal and advises them, "Walk forward without fear" and asks, "Is there aught else that the Servant of the great Name can do for those who speak that name?"[5] Some modern works on art history still repeat the old misidentification,[8] but Near Eastern scholars now generally refer to the "Nisroch" figure as a "griffin-demon".[8]

In 2016, during its brief conquest of the region, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) demolished Ashurnasirpal II's ziggurat of Ninurta at Kalhu.[9] This act was in line with ISIL's longstanding policy of destroying any ancient ruins which it deemed incompatible with its militant interpretation of Islam.[9] According to a statement from the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR)'s Cultural Heritage Initiatives, ISIL may have destroyed the temple to use its destruction for future propaganda[9] and to demoralize the local population.[9]

Notes

References

- Black & Green 1992, p. 142.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 138.

- Mark 2017.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 71.

- Robson 2015.

- Penglase 1994, p. 42.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 71, 138.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 143.

- Lewis 2016.

- Penglase 1994, p. 43.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 142–143.

- Penglase 1994, p. 44.

- van der Toorn, Becking & van der Horst 1999, p. 628.

- Kasak & Veede 2001, pp. 25–26.

- Holland 2009, p. 117.

- Penglase 1994, p. 100.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 101.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 39.

- Jacobsen 1946, pp. 128–152.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 44–45.

- Black, Cunningham & Robson 2006, p. 106.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 108.

- Leick 1998, p. 88.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 42–43.

- Penglase 1994, p. 68.

- Penglase 1994, p. 56.

- Penglase 1994, p. 55.

- Penglase 1994, p. 52.

- Leick 1998, p. 9.

- Leick 1998, p. 10.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 52–53.

- Leick 1998, pp. 9–10.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 173.

- Penglase 1994, p. 53.

- Penglase 1994, p. 45.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 53–54.

- Penglase 1994, p. 54.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 46, 54.

- Penglase 1994, p. 61.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 179.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 43–44, 61.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 52–53, 62.

- Penglase 1994, p. 53, 63.

- van der Toorn, Becking & van der Horst 1999, p. 627.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 138, 142.

- Metzger & Coogan 1993, p. 218.

- van der Toorn, Becking & van der Horst 1999, pp. 627–629.

- Wiseman 1979, p. 337.

- Wildberger 2002, p. 405.

- Gallagher 1999, p. 252.

- van der Toorn, Becking & van der Horst 1999, p. 629.

- Bunson 1996, p. 199.

- Ripley & Dana 1883, pp. 794–795.

- Milton & Flannagan 1998, p. 521.

Bibliography

- Black, Jeremy A.; Cunningham, Graham; Robson, Eleanor (2006), The Literature of Ancient Sumer, Oxford University Press, p. 106, ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0714117056CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunson, Matthew (1996), Angels A to Z: A Who's Who of the Heavenly Host, New York City, New York: Three Rivers Press, ISBN 0-517-88537-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gallagher, William R. (1999), Sennacherib's Campaign to Judah: New Studies, Leiden, The Netherlands, Köln, Germany, and Boston, Massachusetts: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11537-4, ISSN 0169-9024CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holland, Glenn Stanfield (2009), Gods in the Desert: Religions of the Ancient Near East, Lanham, Maryland, Boulder, Colorado, New York City, New York, Toronto, Ontario, and Plymouth, England: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., ISBN 978-0-7425-9979-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (1946), "Sumerian Mythology: A Review Article", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 5 (2): 128–152, doi:10.1086/370777, JSTOR 542374CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kasak, Enn; Veede, Raul (2001), Kõiva, Mare; Kuperjanov, Andres (eds.), "Understanding Planets in Ancient Mesopotamia" (PDF), Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore, Tartu, Estonia: Folk Belief and Media Group of ELM, 16: 7–33, ISSN 1406-0957CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961) [1944], Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-1047-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leick, Gwendolyn (1998) [1991], A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology, New York City, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19811-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Danny (15 November 2016), "ISIS Has Destroyed a Nearly 3,000-Year-Old Assyrian Ziggurat: The ziggurat of Nimrud was the ancient city's central temple", Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian InstitutionCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mark, Joshua J. (2 February 2017), "Ninurta", Ancient History Encyclopedia, archived from the original on 6 January 2018, retrieved 6 June 2018CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (1993), The Oxford Guide to People and Places of the Bible, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195146417.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-534095-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milton, John; Flannagan, Roy (1998), The Riverside Milton, Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-395-80999-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Penglase, Charles (1994), Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, New York City, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-15706-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A. (1883), "Demonology", The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary for General Knowledge, New York City, New York: D. Appleton and CompanyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robson, Eleanor (2015), "Ninurta, god of victory", Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education AcademyCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (second ed.), Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-2491-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wildberger, Hans (2002), Isaiah 28-39: A Continental Commentary, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, ISBN 0-8006-9510-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiseman, D. J. (1979) [1915], "Assyria", in Bromiley, Geoffrey W.; Harrison, Everett F.; Harrison, Roland K.; LaSor, William Sanford; Smith, Edgar W., Jr. (eds.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, 1: A-D, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-3781-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ningirsu. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ninurta |

- Texts

- Commentary

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)