Graysonia, Arkansas

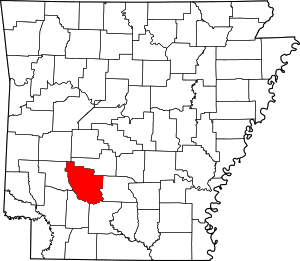

Graysonia was once a boomtown in Clark County, Arkansas, United States, but has since become a ghost town. It is located on a dirt road in what is now known locally as "the middle of nowhere", halfway between Arkadelphia and Alpine. There are no populated communities in its vicinity and only a few scattered residences within a few miles of the former town's location. In the early 20th century, Graysonia was a main hub for the local timber industry. It had a population of actual residents estimated at better than 1,000.

History

In 1902 businessmen William Grayson and Nelson McCleod became principal shareholders in the "Arkadelphia Lumber Company". They made the decision to move their operations along the Antoine River due to their previous location no longer having the resources they needed to be productive. The community was named "Graysonia" after William Grayson. At its founding, the community had a population of 350 people, which would more than double shortly thereafter. The high lumber demands brought on by World War I made the mill in Graysonia one of the most productive in the south. The more than 500 employees were soon producing over 150,000 board feet (350 m3) per day, substantially more than any other mill in the south. Most mills at that time were averaging 25,000 board feet (59 m3) per day. The "Memphis Dallas and Gulf" railroad ran its route between 1909 and the mid-1930s. Around 1907, several kilns, a fire house, a water reservoir, the main mill house and some shotgun houses were built. Within a decade there were several hundred houses, a hillside restaurant and some small cafés, three hotels and a number of large mill buildings.

Although it was a "company owned town", Graysonia elected its town officials, and it became incorporated. Soon the town had its own movie theater, three hotels, a school and a church, along with a running water system and electricity. In 1924, the Bemis family bought into the corporation, and it became the "Ozan-Graysonia Lumber Company". The Bemis family were major mill owners, owning the Ozan Lumber Company, and for the next five years the company saw its greatest success. The decline of the town was due mainly to the company operating on a "cut and move" mentality, meaning they used the resources readily available, then moved on to another location.

However, the Great Depression also contributed to its demise. Beginning in 1929, the depression swept across the country. For a time, the mill at Graysonia held on, and the planer mill lasted for a while cutting stored lumber. The company considered opening several small mills in Graysonia to continue production, but the depression worsened and the mill was closed. For a time starting in 1930, residents were encouraged to stay in Graysonia due to there being employment in the cinnabar mines south of Amity during the Quicksilver Rush. However, the mining operations were short-lived, and the residents began moving to other communities. Within a very short time, the town was deserted.

In 1937 much of the equipment used at Graysonia was moved to be used in a mill in Delight, Arkansas. In 1950 the Graysonia Post Office closed, routing its mail through Alpine. That same year the US Census listed Graysonia's population as "zero". The last known inhabitant was Brown Hickman, a retired logger who left the town in 1951. All that remains today are the foundations of a few buildings.

The train used in Steven Spielberg's mini series Into the West was originally built for use in Graysonia. Logging towns like Graysonia were common in Arkansas in this period, due to an abundance of virgin timber and the desire by companies to cut it. Few of the towns, although all thrived for a time, survive today. Two such towns, Mauldin, Arkansas and Rosboro, Arkansas, were extremely successful during the same period that Graysonia existed. Today, the company that formed both of those towns, Caddo River Timber Company (Now Rosboro Timber Company), is one of the largest private timber holders of the Pacific Northwest, and is based in Springfield, Oregon.