Gray-shanked douc

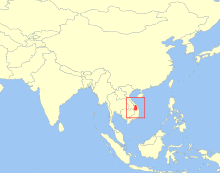

The grey-shanked douc langur (Pygathrix cinerea) is a douc species native to the Vietnamese provinces of Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi, Bình Định, Kon Tum, and Gia Lai. The total population is estimated at 550 to 700 individuals.[3] In 2016, Dr Benjamin Rawson, Country Director of Fauna & Flora International - Vietnam Programme, announced a discovery of an additional population including more than 500 individuals found in Central Vietnam, bringing the total population up to approximately 1000 individuals.[4]

| Grey-shanked douc langur[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Genus: | Pygathrix |

| Species: | P. cinerea |

| Binomial name | |

| Pygathrix cinerea (Nadler, 1997) | |

| |

| Geographic range | |

Taxonomy

P. cinerea was originally described as a subspecies of P. nemaeus in 1997,[5] but later elevated to species status due to morphological differences. Other research has shown significant genetic differences as well.[6] This species does sometimes hybridize with P. nemaeus.[3][7]

Physical description

Grey-shanked doucs are very similar in appearance to P. nemaeus. They are light grey with a pale underside. Their feet and hand are black and their shins are a dark grey. The face is brownish orange on top with a white chin. Hair around the chin is white. The throat is white and lined on the bottom with an orange, brown collar. Males are slightly larger than females averaging 10.9 kg. Females average about 8.2 kg.[8]

Behavior

Grey-shanked doucs are diurnal and primarily arboreal. They move about through trees by jumping and brachiating. In the past they have been found in groups as large as fifty individuals but those numbers have been greatly reduced to 4 to 15 individuals. Males are the dominant gender and dominance hierarchies have been observed while in captivity.[8]

The grey-shanked douc langur communicates using touch, visual communication, and sound. Growls are used to show aggression. They can be used as a threat or warning toward other individuals. A soft, twitter sound is used when being submissive.[9]

Grey-shanked doucs also engage in grooming to remove parasites and to establish and strengthen bonds between group members. This is usually done before resting for the night. Group members will also spar with each other. Sparring is a type of aggressive behavior in which participants will slap, pull, and grab each other.[9]

Visual communication includes facial expressions and various postures. Facial expressions include grimacing, which is used to show submissiveness, play face, which is used to play with another group member, and staring which suggests either curiosity or aggression. Facial expressions are also used during courtship. The male will make faces at the female indicating that he is ready to copulate.[9]

Grey-shanked langurs are primarily folivourous but will also eat other plant parts such as seeds, fruits, and flowers. They prefer young leaves and fruit that has not yet fully ripened.[10]

Reproduction

The breeding season usually occurs between August and December and gestation is about 165 to 190 days. When courting, potential mates will use facial expressions to indicate that they are ready to copulate. One will thrust its jaw forward, shake its head, and raise and lower its eyebrows. The other will then respond with the same action. This may be repeated several times. The female then presents herself to the male.[11]

Births usually occur between January and August, during the fruiting season. The mother will give birth to one offspring weighing 500 g to 720 g. Females are sexually mature at about four years of age.[11]

Conservation

The grey-shanked douc langur is listed on the IUCN Red List as critically endangered.[12] It is one of "The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates."[13]

Hunting has been a major problem for grey-shanked doucs. They are hunted for bush meat and for traditional medicine purposes. Their bones are used to make a substance called "monkey bone balm" which is thought to improve hemoglobin regeneration and renal function. Monkey bone balm is also believed to treat lack of appetite, insomnia, and anemia. Grey-shanked doucs are also used in the exotic wild life trade. The adults are killed and the infants are taken and sold as pets. The Vietnam War also played a big part in reducing the population. Soldiers would use the monkeys for target practice. Deforestation and habitat fragmentation are also major threats. Laws are in place to prevent the destruction of their habitat and to prevent hunting, but although these laws have not been strongly enforced,[3] that may be changing.[14]

Researchers have concluded that due to the major deforestation and climate change of these provinces of Vietnam, that the population of the Grey-shanked duoc will sharply decline in the next coming years (Vu et al., 2020). Their species will be pushed into a high mountainous area with little to no resources for survival (Tran et al., 2018)

Studies are under way to learn more about the distribution, range, and behavior of grey-shanked doucs. These studies will help experts to find more ways to conserve this species. A long term study in the Gia Lai Provence is currently being conducted as a part of the Frankfurt Zoological Society's Vietnam Primate Conservation Program.[3] The Frankfurt Zoological Society also works with the Endangered Primate Rescue Center which has an ongoing Captive Breeding program.[2]

On July 3, 2007, it was reported that the WWF and Conservation International had monitored at least 116 of the primates in central Vietnam, increasing its chances of survival.[15]

In the Central Highlands, Gray-shanked douc Langurs were tortured and murdered by Vietnamese troops who posted pictures of it online.[16]

On March 3, 2016, Fauna & Flora International announced that a new population of over 500 grey-shanked doucs had been discovered in Central Vietnam.[17]

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Ngoc Thanh, V.; Lippold, L.; Nadler, T. & Timmons, R. J. (2008). "Pygathrix cinerea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T39827A10273229. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T39827A10273229.en.

- Long, H. 2004. "Distribution and status of the greyshanked douc langur (Pygathrix cinerea) in Vietnam". In Conservation of Primates in Vietnam, 22: 52-57.

- "Vietnamese primatologists discover 500 grey-shanked douc langurs". VietNam News. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Nadler, T. 1997. "A new subspecies of Douc langur, Pygathrix nemaeus cinereus ssp. nov." Zoologische Garten 4: 165-176.

- Roos, C. and Nadler, T. 2001. "Molecular evolution of the douc langurs". Zoologische Garten 71(1): 1-6.

- Long, H. 2007. "Distribution, population and conservation status of the grey-shanked". Vietnamese Journal of Primatology, 1: 55-60.

- Covert, H., T. Nadler, N. Stevens, K. Wright. 2008. "Comparisons of Suspensory Behaviors Among Pygathrix cinerea, P. nemaeus, and Nomascus leucogenys in Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam". International Journal of Primatology, 29: 1467-1480.

- Primate Info Net, 2009. "Douc Langur (Pygathrix cinerea)" (On-line). Wisconsin Primate Research Center. Accessed December 10, 2009 at http://pin.primate.wisc.edu/factsheets/links/pygathrix.

- 2008. "Southeast Asian Mammal Databank" General Info. Species Index. Accessed Dec 10, 2009.

- Ademmer, C., K. Klumpe, I. Maravic, C. Königshofen, C. Schwitzer. 2002. Nahrungsaufnahme und Hormonstatus von Kleideraffen (Pygathrix n. nemaeus Linnaeus, 1771). im Zoo. Z. Kölner Zoo, 45: 129-135.

- Ngoc Thanh, V., Lippold, L., Nadler, T. & Timmins, R.J. 2008. Pygathrix cinerea. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 15 December 2009.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Wallis, J.; Rylands, A.B.; Ganzhorn, J.U.; Oates, J.F.; Williamson, E.A.; Palacios, E.; Heymann, E.W.; Kierulff, M.C.M.; Long Yongcheng; Supriatna, J.; Roos, C.; Walker, S.; Cortés-Ortiz, L.; Schwitzer, C., eds. (2009). "Primates in Peril: The World's 25 Most Endangered Primates 2008–2010" (PDF). Illustrated by S.D. Nash. Arlington, Virginia.: IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), and Conservation International (CI): 1–92. ISBN 978-1-934151-34-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-10. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Staff (20 July 2012). "Vietnamese soldiers held over deaths of rare monkeys". BBC News.

- "Scientists find endangered monkey in Vietnam". Yahoo! News. July 3, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- Cota-Larson, Rhishja (July 26, 2012). "Vietnam: Soldiers Arrested for Torturing, Killing Endangered Langurs". Annamaticus.

- "Over 500 critically endangered doucs discovered in Vietnam". TuoiTreNews.vn. 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.