Gray-bellied caenolestid

The gray-bellied caenolestid (Caenolestes caniventer), or grey-bellied shrew opossum, is a shrew opossum found in humid, temperate forests and moist grasslands of western Ecuador and northwestern Peru. It was first described by American zoologist Harold Elmer Anthony in 1921. Little is known about the behavior of the gray-bellied caenolestid. It appears to be terrestrial (land-living) and crepuscular (active around twilight) or nocturnal (active at night). Diet consists of invertebrate larvae, small vertebrates and plant material. The IUCN classifies the gray-bellied caenolestid as near threatened.

| Gray-bellied caenolestid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Caenolestes caniventer in El Oro Province, Ecuador | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Paucituberculata |

| Family: | Caenolestidae |

| Genus: | Caenolestes |

| Species: | C. caniventer |

| Binomial name | |

| Caenolestes caniventer Anthony, 1921 | |

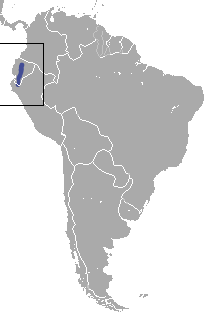

| |

| Range of the gray-bellied caenolestid | |

Taxonomy and etymology

The gray-bellied caenolestid is one of the five members of Caenolestes, and is placed in the family Caenolestidae (shrew opossums). It was first described by American zoologist Harold Elmer Anthony in 1921.[2] In the latter part of 20th century, scientists believed that Caenolestes is closely related to Lestoros (the Incan caenolestid).[3][4] Over the years, it became clear that Lestoros is morphologically different from Caenolestes.[5] A 2013 morphological and mitochondrial DNA-based phylogenetic study showed that the Incan caenolestid and the long-nosed caenolestid (Rhyncholestes raphanurus) form a clade sister to Caenolestes. The cladogram below is based on this study.[6]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Caenolestid fossils date to as early as the early Eocene (nearly 55 mya). The generic name Caenolestes derives from the Greek words kainos ("new") and lestes ("robber", "pirate").[7]

Ecology and behavior

Little is known about the behavior of the gray-bellied caenolestid. It appears to be terrestrial (land-living) and crepuscular (active around twilight) or nocturnal (active at night).[1] It appears to be an "opportunistic feeder". Analysis of stomach contents of individuals from Peru suggested a diet comprised largely (up to 75%) by invertebrate larvae (such as arachnids and centipedes); small vertebrates and plant material are also consumed.[8] A pregnant female captured in Ecuador was found to have two fetuses in its womb.[9]

Distribution and status

The gray-bellied caenolestid inhabit cool, moist areas with good cover; it is known from humid, temperate forests at altitudes of up to 2,900 metres (9,500 ft), and moist grasslands in the subtropics. It occurs in small tunnels under tree roots by streams.[8] The range covers western Ecuador and northwestern Peru. The IUCN classifies the gray-bellied caenolestid as near threatened. Its population has decreased by nearly 20% since the 1990s; numbers are feared to be declining due to deforestation and agricultural expansion.[1] The gray-bellied caenolestid occurs in Cajas National Park and Mazán Ecological Reserve.[10]

References

- Solari, S.; Martínez-Cerón, J. (2015). "Caenolestes caniventer". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2015: e.T40521A22180055. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T40521A22180055.en. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Gardner, A.L. (2005). "Order Paucituberculata". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Simpson, G.G. (1970). "The Argyrolagidae, extinct South American marsupials". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 139: 1–86.

- Marshall, L.G. (1980). "Systematics of the South American marsupial family Caenolestidae". Fieldiana: Geology. New Series. 5: 1–145.

- Gardner, A.L., ed. (2007). Mammals of South America. 1. Chicago, US: University of Chicago Press. pp. 121, 124–6. ISBN 978-0-226-28242-8.

- Ojala-Barbour, R.; Pinto, C.M.; Brito M., J.; Albuja V., L.; Lee, T.E.; Patterson, B.D. (2013). "A new species of shrew-opossum (Paucituberculata: Caenolestidae) with a phylogeny of extant caenolestids". Journal of Mammalogy. 94 (5): 967–82. doi:10.1644/13-MAMM-A-018.1.

- Patterson, B.D.; Gallardo, M.H. (1987). "Rhyncolestes raphanurus" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 286: 1–5.

- Barkley, L.J.; Whitaker, J.O. (1984). "Confirmation of Caenolestes in Peru with Information on diet". Journal of Mammalogy. 65 (2): 328–30. doi:10.2307/1381173.

- Barnett, A.A. (1991). "Records of the grey-bellied shrew opossum, Caenolestes caniventer and Tate's shrew opossum, Caenolestes tatei (Caenolestidae, Marsupialia), from Ecuadorian montane forests" (PDF). Mammalia. 55 (3): 443–5. doi:10.1515/mamm.1991.55.3.433.

- Barnett, A.A. (1999). "Small mammals of the Cajas Plateau. southern Ecuador: ecology and natural history" (PDF). Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 42 (4): 161–217.

External links