Gravitational anomaly

In theoretical physics, a gravitational anomaly is an example of a gauge anomaly: it is an effect of quantum mechanics — usually a one-loop diagram—that invalidates the general covariance of a theory of general relativity combined with some other fields. The adjective "gravitational" is derived from the symmetry of a gravitational theory, namely from general covariance. A gravitational anomaly is generally synonymous with diffeomorphism anomaly, since general covariance is symmetry under coordinate reparametrization; i.e. diffeomorphism.

General covariance is the basis of general relativity, the classical theory of gravitation. Moreover, it is necessary for the consistency of any theory of quantum gravity, since it is required in order to cancel unphysical degrees of freedom with a negative norm, namely gravitons polarized along the time direction. Therefore, all gravitational anomalies must cancel out.

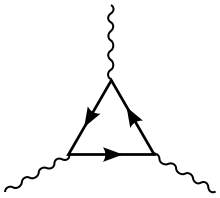

The anomaly usually appears as a Feynman diagram with a chiral fermion running in the loop (a polygon) with n external gravitons attached to the loop where where is the spacetime dimension.

Gravitational anomalies

Consider a classical gravitational field represented by the vielbein and a quantized Fermi field . The generating functional for this quantum field is

where is the quantum action and the factor before the Lagrangian is the vielbein determinant, the variation of the quantum action renders

in which we denote a mean value with respect to the path integral by the bracket . Let us label the Lorentz, Einstein and Weyl transformations respectively by their parameters ; they spawn the following anomalies:

Lorentz anomaly

,

which readily indicates that the energy-momentum tensor has an anti-symmetric part.

Einstein anomaly

,

this is related to the non-conservation of the energy-momentum tensor, i.e. .

Weyl anomaly

,

which indicates that the trace is non-zero.

See also

References

- Alvarez-Gaumé, Luis; Edward Witten (1984). "Gravitational Anomalies". Nucl. Phys. B. 234 (2): 269. Bibcode:1984NuPhB.234..269A. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(84)90066-X.