Gongo Soco

Gongo Soco was a gold mine in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to the east of Belo Horizonte in the mid-19th century. It was worked by skilled miners from Cornwall and by less skilled Brazilian labourers and slaves. Machinery powered by a water wheel and a steam engine was used to pump out the mine, operate the lifts, and operate the grinding mills where the gold was separated from the ore. The mine was closed when the gold ran out, but was later reopened as an iron ore mine. Recently the iron mine was also closed.

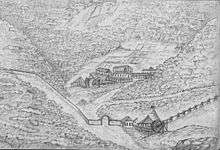

The old Gongo Soco mine in 1839, sketch by Ernst Hasenclever | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Gongo Soco | |

| Location | Barão de Cocais |

| State | Minas Gerais |

| Country | Country |

| Coordinates | 19°57′51.0″S 43°35′53.0″W |

| Production | |

| Products | Gold, iron |

| History | |

| Opened | 1826 |

| Active | 1826–1856 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Vale |

Etymology

The origins of the name "Gongo Soco" are obscure. One version is that when there was a theft in the mine a gong was sounded, but nobody listened.[1] Another is that a slave from the Congo was found squatting ("soco") while burying a gold deposit.[2]

Gold mine

A Bitencourt prospector found gold in a stream that cuts through the region in 1745. The land was later inherited by João Baptista Ferreira de Souza Coutinho, Baron of Catas Altas. He sold it to the Imperial Brazilian Mining Association, based in Cornwall, England, for £79,000 in 1825.[3] The company converted the alluvial gold extraction operation into mechanised underground mining and gold extraction. From 1826 to 1856 the mine produced over 12,000 kilograms (26,000 lb) of gold.[1]

A German visitor, Ernst Hasenclever, visited the mine in 1839, when Gongo Soco was the largest gold mine in Brazil.[4] The mine had a smithy where all the tools and instruments need for the mine were made, and a large 3-story warehouse holding provisions that also served as housing for the English miners. There was a hospital, which looking like a barracks to Hasenclever.[5] The hospital building was carefully planned, with central corridors, large rooms with two windows each and up to eight beds, and a sophisticated ventilation system to avoid humidity in the basement.[3]

A steam engine above the mine shaft turned a double wheel that drove a long chain to haul up containers of ore and lower down logs. The main corridors were about 6 feet (1.8 m) high and contained iron rails on which wagons were pushed for about 200 yards (180 m). Loads of gravel extracted from the side galleries using drills and sledgehammers were hoisted by a simple winch and transported by wagon to a grinding mill. One black slave could easily push two wagons.[6] The deposits at Gongo Soco were in weak rock formations, so large tree trunks from a forest 6 miles (9.7 km) away were needed to prop up the gallery ceilings. The mine had a large drainage pump driven by a water wheel, which also drove the grinding mills. The water was pumped up 330 feet (100 m), and was used to power a sawmill lower down the slope.[7]

The mine had nine grinding mills, each with 12–24 wooden hammers with iron heads weighing 150 to 200 kilograms (330 to 440 lb). The gravel from the mine was placed in an iron container, then pounded into dust by the hammers, which were driven by a wooden wheel.[8] The dust was washed from the container by a fast current of water running through a cloth-lined trough. The heavy gold fell into the cloth, while lighter elements were washed out at the end. The cloth was then washed to remove the gold dust. The work continued day and night.[9]

In 1839 a record of 1,900 kilograms (4,200 lb) of gold was extracted. However, the machinery was not powerful enough to reach the deeper veins.[3] Only 29 kilograms (64 lb) were produced in 1856, and the mine was closed. Later gold extraction was replaced by iron mining.[1]

.jpg)

Workers

The company hired skilled miners from Cornwall and used Brazilians and slaves for unskilled work. The climate was considered healthy, with temperatures from 45 to 85 °F (7 to 29 °C).[10] At first the mine had a superintendent, two mine captains and 31 miners and artisans.[3] In 1839 the mine director received an annual salary of £3,500. Under him there were four captains, eight officers and eighty British miners who were assisted by 650 slaves owned by the Imperial Brazilian Mining Association. Each English miner received a yearly wage of £80, paid in monthly instalments.[5] Many of the Cornish workers brought their families with them, encouraged to do so by the mine captain William Jory Henwood. They were on 3–5 year contracts, so there was constant contact with Cornish mining communities such as Gwennap and Redruth through miners travelling to and from Brazil.[10]

Hasenclever said a "black inspector" (Negerinspektor) was responsible for the slaves, including their food, clothing, housing and discipline.[5] Women slaves were employed above ground, mainly in washing the gold-bearing sand.[11] Although Hasenclever wrote that Gongo Soco had 650 slaves in 1839, probably not all the black workers were slaves as he thought. There would have been free blacks working with the slaves, doing the same work but for pay. Another source gives the total in 1838 as 413 slaves, 148 Europeans and 190 Brazilians, totalling 751 people. Yet another source estimates that in 1840 there were 500 slaves, 200 Brazilian free workers and 51 Europeans.[12] A doctor and a priest served all the workers, including slaves.[5]

Village

A village grew up about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) from the mine in the wooded valley of the Gongo Soco River. The single-story buildings surrounded a church among banana trees. The former home of the Baron of Catas Altas was occupied by the superintendents of the mine.[3] The Casa Grande housed the director and first commissioner, and their families, and also held the mine's administrative and accounting offices.[5] The Casa Grande was a large building where the company commissioner would hold parties on Saturday evenings. Concerts and dances were also arranged at the Casa Grande.[10] The slaves lived apart from the Cornish to avoid contact and friction. Henwood opened a school for the children of the slaves.[10]

A company store sold a range of household goods. There was a market every Saturday where the miners could buy chickens, eggs, fruit and vegetables. Some miners hired a local woman as a cook. The mine had a good library. There was a Catholic church for the slaves and Brazilians, and an Anglican church for the Protestants. Many of the Cornish were Wesleyan Methodists, and used the fields or their houses for prayer and study meetings. Often they grew flowers and vegetables in their gardens from seeds brought from Cornwall.[10] After the mine closed in 1856 some of the Cornish miners went back to Cornwall while some found work in other Brazilian mines such as those operated by the Saint John d'El Rey Mining Company.[10]

Ruins

.jpg)

There are two sets of ruins from the old Gongo Soco mine. Sector 1 contains the mine itself and its industrial structures. Sector 2, some distance away, holds the housing and infrastructure of the former village. According to the 1931 census the village had 30 stone houses along a 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) road. It included the Cemitério dos Ingleses, where the British workers were buried, and where ten tombstones have been found with English inscriptions. There are traces of a hospital and two churches, one Catholic and the other Anglican.[1]

It has been conjectured that the house of the Baron of Catas Altas covered 1,000 square metres (11,000 sq ft), assuming it was one story high. Near Sector 1 there is a chimney 5.2 metres (17 ft) high and 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in) wide. Along the road to the right there is a stone wall almost 60 metres (200 ft) long ending in an arched gateway, presumably erected to mark the visits of emperors Pedro I in 1831 and Pedro II in 1881. The ruined arch is covered by a fig tree. To the left is what the traveller Richard Francis Burton says would have been a dressing room.[1]

Iron mine

Gongo Soco was abandoned until it was acquired in 1986 by Mineração Socoimex, which maintained the remains of the former gold mine.[3] On 11 May 2000 CVRD (Vale) acquired full control of Socoimex, which was extracting and selling iron ore from the Gongo Sôco Mine. The mine had proven reserves of about 75 million tons of high grade hematite, and could produce about 7 million tons annually.[13] In 2011 Vale said it could extend operations at the mine for a few more years, but was preparing to complete the project, with the transfer of 350 employees to other units. Vale said that high extraction costs and the low price of ore made operations uneconomical.[14] In April 2016 it was announced that Vale was closing the Gongo Soco mine at the end of the month and laying off 90 employees. Production had dropped from about 6 million tons per year to about 4 million. The chief executive said he expected the workers would be relocated to other Vale units.[15]

Notes

- Conjunto de ruínas do Gongo Soco – IEPHA, p. 1.

- Conjunto de ruínas do Gongo Soco – IEPHA, p. 1–2.

- Ruínas do Gongo Soco – DescubraMinas.com.

- Alves 2014, p. 2.

- Alves 2014, p. 5.

- Alves 2014, p. 7.

- Alves 2014, p. 8–9.

- Alves 2014, p. 7–8.

- Alves 2014, p. 8.

- Gongo Soco – The Cornish in Latin America.

- Alves 2014, p. 12.

- Alves 2014, p. 9.

- CVRD Acquired SOCOIMEX – Vale.

- Com Gongo Soco fechada ... 2016.

- Mina de Gongo Soco ... encerra atividades.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gongo Soco (former gold mine). |

Sources

- Alves, Débora Bendocchi (2014), "Ernst Hasenclever em Gongo-Soco: exploração inglesa nas minas de ouro em Minas Gerais no século XIX" (PDF), Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos (in Portuguese), 21 (1), ISSN 0104-5970, retrieved 2016-08-12

- "Com Gongo Soco fechada, Nozinho e prefeito de Barão pedem agilidade em liberação de outros projetos mineradores", De Fato Online (in Portuguese), 28 April 2016, archived from the original on 24 September 2016, retrieved 2016-08-12

- Conjunto de ruínas do Gongo Soco (in Portuguese), IEPHA: Instituto Estadual do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico de Minas Gerais, archived from the original on 2016-09-16, retrieved 2016-08-12

- CVRD Acquired SOCOIMEX (in Portuguese), Vale, 15 May 2000, retrieved 2016-08-12

- "Gongo Soco", The Cornish in Latin America, University of Exeter, retrieved 2016-08-12

- Mina de Gongo Soco, em Barão de Cocais, encerra atividades (in Portuguese), 22 April 2016, retrieved 2016-08-12

- "Ruínas do Gongo Soco", DescubraMinas.com (in Portuguese), SENAC MINAS, retrieved 2016-08-12