Gondibert

Gondibert is an epic poem by William Davenant. In it he attempts to combine the five-act structure of English Renaissance drama with the Homeric and Virgilian epic literary tradition. Davenant also sought to incorporate modern philosophical theories about government and passion, based primarily in the work of Thomas Hobbes, to whom Davenant sent drafts of the poem for review.[1]

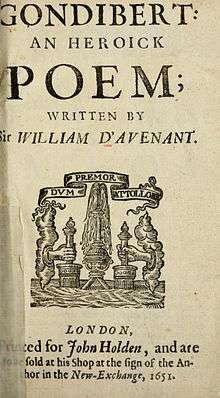

The title page of the 1651 edition of Gondibert | |

| Author | William Davenant |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Epic poetry |

| Publisher | John Holden (original) |

Publication date | 1651 |

| Media type | |

A lengthy philosophical preface takes the form of a letter to Hobbes, and is printed in the first edition with Hobbes' own reply and comments. Though Davenant asserted that the completed work would be in five sections or "books", only the first two books and part of the third book were completed.

Publication history

The philosophical Preface with Hobbes's reply to Davenant appeared, along with a few stanzas of the poem, in an edition published during Davenant's exile in Paris in 1650. There were two editions of the partially completed text in London in 1651. A 1652 edition contains the first two books and part of the third. This version is also prefaced by commendatory poems written by Edmund Waller and Abraham Cowley.[2] Some additional material was included in an edition published after Davenant's death.

Plot

The plot of the poem is loosely based on episodes of Paul the Deacon's History of the Lombards.[3] The poem tells the story of an early medieval Lombard Duke called Gondibert and his love for the beautiful and innocent Birtha. His love for Birtha means he cannot return the affections of princess Rhodalind, the king's daughter, even though he would be made ruler of Verona if he married her. Rhodalind, in turn, is loved by Oswald. These various conflicts of desire and devotion occasion philosophical reflections on the nature of love, duty and loyalty. The story is never resolved, since the poet gave up on the work before completing his design.

Interpretations

The poem has been interpreted as an allegory of the power struggles of the English Civil War, during which Davenant was a prominent Royalist. Gondibert himself has been identified with Charles II and Rhodalind with Henrietta Maria. According to Kevin Sharpe, the allegorical aspects can be overstated, but "certain passages seem clearly to allegorise specific events. The hunting of the stag in the second canto of book one strongly suggests the pursuit of Charles I. Suggestions of this sort are undoubtedly convincing in general, even if they don't work out so well in particular."[1]

The poem adopts the view that the chivalric ideal of love represents the sublimation of desire into duty, and that this personal model of devoted love stands for the political ideal of aristocratic government by the finest and best educated of persons in society, whose sensibilities are refined by courtly life and culture.[1] Victoria Kahn argues that the politics of love is central to Davenant's argument "that poetry could instill political obedience by inspiring the reader with love. Romance was not simply a powerful generic influence on Gondibert, it was also Davenant's model for the poet's relation to the reader."[4]

Influence

The poem introduced the "Gondibert stanza", a decasyllabic quatrain in pentameters rhyming abab. It was adopted by Waller in A panegyrick to my Lord Protector (1655) and by John Dryden in Heroic Stanzas on the Death of Oliver Cromwell and Annus Mirabilis. John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester uses it satirically in The Disabled Debauchee. According to the Cambridge History of Early Modern English Literature "Dryden revives this measure to make his peace with the 1650s and advertise his bid to continue Davenant's Laureate project, but it would soon be wickedly parodied in Rochester's 'Disabled Debauchee'."[5]

Andrew Marvell's poem Upon Appleton House is often interpreted as a republican reply to the royalist message of Gondibert, which contrasts the fantasy world of Davenant's poem with the real domestic haven created by the retired Parliamentarian commander Thomas Fairfax.[6]

William Thompson's play Gondibert And Birtha: A Tragedy (1751) was based on the poem. Alexander Chalmers wrote of the play that "although it is not without individual passages of poetical beauty, it has not dramatic form and consistency to entitle it to higher praise."[7] Hannah Cowley's play Albina (1779) is much more loosely derived from it. The character of Sir Gondibert also made a brief reappearance in English literature in "Calidore: A Fragment," an early unfinished poem by John Keats heavily influenced by Edmund Spenser.[8]

In the "Former Inhabitants; and Winter Visitors" chapter of Walden, American author and naturalist Henry David Thoreau tells a story of once being interrupted of reading Davenant's "Gondibert" by a fire that broke out in his hometown of Concord, Massachusetts. He had been working his way through Alexander Chalmers' 21-volume set, The Works of the English Poets, From Chaucer to Cowper, which he checked out of the Harvard College library. The text of "Gondibert" appears in the sixth volume.[9]

References

- Kevin Sharpe, Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the England of Charles I, Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp.102-3

- Vivian de Sola Pinto, The English Renaissance, 1510-1688, Cresset Press, London, 1938, p.332

- Nicholas Birns, Barbarian Memory, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, p. 33.

- Victoria Kahn, Wayward Contracts: The Crisis of Political Obligation in England, 1640-1674, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2004, p.144.

- The Cambridge History of Early Modern English Literature. David Loewenstein, Janel Mueller (eds) Cambridge University Press, 2003, p.823.

- Philip Hardie; Helen Moore (14 October 2010). Classical Literary Careers and Their Reception. Cambridge University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-521-76297-7. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- Chalmers, Alexander, "Life of William Thompson", Works of the English Poets, London , 1819, p.4

- "4. Calidore: A Fragment. Keats, John. 1884. The Poetical Works of John Keats". www.bartleby.com.

- Henry David Thoreau (1919). Walden: Or, Life in the Woods. Houghton, Mifflin Company. p. 283. Retrieved 22 December 2019.