Glan Valley Railway

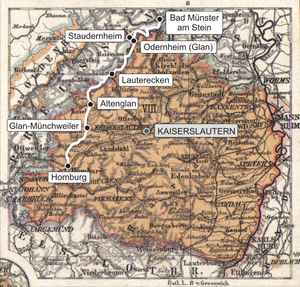

The Glan Valley Railway (German: Glantalbahn) is a non-electrified line along the Glan river, in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It consists of the Glan-Münchweiler–Altenglan section, which was built as part of the Landstuhl–Kusel railway and sections that were built later for military reasons: Homburg–Glan-Münchweiler, Altenglan–Staudernheim and Odernheim–Bad Münster am Stein. The line had strategic importance, otherwise traffic was rather low, except on the Glan Munchweiler–Altenglan section.

| Glan Valley Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | Glantalbahn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Homburg Bad Münster am Stein | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line number | 3281 (Homburg – Staudernheim) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route number | last 641, before 1970 272d | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The line runs right next to the river for 60 km of its 85 km length from Homburg to Bad Münster. The line is closed, except for the ten km section from Glan-Münchweiler to Altenglan that forms part of the Landstuhl–Kusel line. It is used for tourism and draisine rides have been offered on the section between Altenglan and Staudernheim since 2000. In contrast, the Waldmohr–Glan-Münchweiler section has been dismantled.

History

Although the possibility of a railway along the Glan to connect the Saar region and the region around Bingen would have been obvious from a geographical perspective, the fact that in the 19th century it would have run across the territory of several countries prevented the realisation of the project for some time. The first efforts were aimed at a railway connecting the north-western Palatinate, starting in 1856. During the construction of the Rhine-Nahe Railway (Rhein-Nahe-Bahn), a proposal was developed to build a railway via Lauterecken, Altenglan and Kusel to St. Wendel and Neunkirchen. However, these efforts were not initially successful, since Prussia demanded to be in charge of the line within its own territory. In addition, the border between Bavaria and Prussia in the middle and lower Glan valley, especially from Altenglan to Staudernheim, was very irregular, making construction difficult.[2]

In 1860, a committee was formed called Notabeln des Glan- und Lautertales (notables of the Glan and Lauter valleys). It campaigned for a line that branched in Kaiserslautern from the Palatine Ludwig Railway (Pfälzischen Ludwigsbahn), then ran via the Lauter and the lower Glan valley and met the Rhine-Nahe Railway in Staudernheim; this line was completed in the same year. Prussia opposed the proposal because it feared that the Nahe line would lose its importance. However, the project received support from Hesse-Homburg, as it would connect its exclave of Meisenheim to the rail network. The Hessian Privy Councillor Christian Bansa also supported the proposed rail link in 1861 in discussions with the Prussian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, arguing that there was a greater need for it than for the planned line along the Alsenz.

However, Prussia was only willing to support the Palatine Northern Railway Company (Gesellschaft der Pfälzischen Nordbahnen), which was established in 1866 and completed the Alsenz Valley Railway in 1871. Its northern end point was in the then Prussian town of Bad Münster. In contrast, neither Bavaria (which then owned some of the territory involved) nor Prussia were interested in guaranteeing the interest on loans for the proposed railway, which in 1873 was estimated to cost a total of about 3.6 million guilders.[3]

Plans for a strategic railway and the opening of the Lauterecken–Staudernheim section

The granting of the concession in the 1860s to build the Kusel-Landstuhl railway, which was opened in 1868 and follows the course of the Glan from Glan Munchweiler to Altenglan, gave new life to the proposal to build a line through the rest of the Glan valley. A company was founded in 1865 in Meisenheim to carry out the planning of this line. However, several wars in the following years at first prevented the completion of the project.[4]

As Alsace and Lorraine were incorporated in the German Empire in 1871 as a result of the Franco-Prussian War, the fear that France would start another war in order to regain Alsace-Lorraine developed in Germany. To prevent this, the primary interest in new railways in south-western Germany towards the end of the 19th century was in railways intended mainly for military purposes. In the Palatinate and Prussia planning started on the strategic railway, which would branch from the Palatine Ludwig Railway in Homburg and follow the Glan river, sharing the Kusel-Landstuhl railway between Glan-Münchweiler and Altenglan. On 7 September 1871, a committee met in Meisenheim to consider the plans developed by engineers for such a line. The committee issued a memorandum on 27 January 1871 that highlighted the economic and the military importance of a railway along the Glan.

However, the opposition of Bavaria prevented the project for the time being; this attitude was due to the high construction costs expected. Because of the border, which would also hinder the construction, there were at the time plans for a branch line from Altenglan to St Julian, which would run exclusively through Bavarian Palatinate.[3]

In 1891, Bavaria and Prussia signed a treaty that included the construction and operation of a line from Lauterecken to Staudernheim as a direct continuation of the Lauterbrunnen Valley Railway of the Palatine Northern Railway Company from Kaiserslautern to Lauterecken;[5] preparatory work for its construction had already begun in 1886. Moreover, the railway entrepreneur Karl Jakob von Lavale had agreed that the Board would be responsible for half the land acquisition costs. The section between Lauterecken and Meisenheim was open on 16 June 1896 and the Lauterecken-Odernheim section was opened in October 1896. Construction work on closing the gap to Staudernheim began on 2 November, but on the same day a flood scoured the embankment at Odenbach and interrupted traffic. The remaining line to Staudernheim on the Nahe Valley Railway was finally taken into operation on 1 July 1897.[6]

Completion of the Glan Valley Railway

At the same time Bavaria reversed its opposition to a strategic railway line along the entire Glan as Germany's relations with France had deteriorated in the meantime. This culminated in an agreement, concluded in November 1900, to build a strategic railway along the Glan, which would be the shortest connection from the Saar region to the Rhine. The main purpose of the route was kept secret, so the Palatine district offices received a circular which prohibited the use of terms such as "strategic line" or "military railway" in public. Nevertheless, an article entitled "Die Strategische Bahn in der Pfalz” (The Strategic Railway in the Palatinate) still appeared two years later in the Pfälzische Presse newspaper.[7]

The plan was for a route with high embankments, which were deemed necessary because of the frequent flooding along the Glan. The strategic line had its starting point in Scheidt, and would continue via Homburg and use the existing Landstuhl–Kusel line between Glan-Munchweiler and Altenglan and the line opened in 1896 between Lauterecken and Odernheim.[6] Both existing lines would be duplicated. The strategic railway was planned to run on the right bank of the Nahe from Odernheim to Bad Münster. It would be necessary to make fundamental changes to the Bad Münster am Stein station.

Construction of the strategic line started in the summer in 1902. From 14 August 1902 materials for the construction of the railway were brought to Ulmet on a narrow gauge railway and by horse-drawn carts from Altenglan. Italian and Croatian construction workers prepared the subgrade from Altenglan to St. Julian. On 27 October of the same year, the Mannheim-based company Grün & Bilfinger started the construction of the section from St. Julian to Lauterecken. The Glan and a parallel road had to be moved at Niedereisenbach. Material obtained in digging a new bed for the Glan River was used for the construction of an embankment for the railway to prevent flooding. The work was carried out by day labourers from Italy. Due to weather conditions in December 1902, work had to be suspended until spring, 1903. The superstructure between Eschenau and Lauterecken was largely completed on 21 January 1904.[7]

As early as 1903, coal trains ran to the Nordfeld Consolidated Coal Mine on the Homburg–Jägersburg section, which had not yet been officially opened. The mine was connected by a branch line, the so-called Nordfeldbahn (northern light railway). However, the mine, along with the branch line was closed two years later due to its unprofitability.[8] Finally, the Glan Valley Railway was opened over its entire length on 1 May 1904, including the newly built Homburg–Glan-Münchweiler, Altenglan–Lauterecken and Odernheim–Bad Münster am Stein sections. There were 26 intermediate stations along the new line.[9]

First years of operation and the First World War (1904–1918)

The new line provided a continuous connection from Homburg via Glan-Münchweiler, Altenglan, Lauterecken-Grumbach and Odernheim to Bad Münster am Stein. The line was originally double track to meet its military requirements as a strategic railway. Altenglan station was rebuilt during the building of the line at the rail junction with diverging platforms and a new entrance building was built. The old Lauterecken station was unsuitable for the junction with the Lauter Valley Railway due to its location on the southern outskirts and it was demoted to a halt and a new Lauterecken-Grumbach station was opened in 1904 as a junction station. It was built immediately to the north of a halt that had opened in 1896 on the Lauter Valley Railway and was closed at the same time as the opening of the new junction station.

The connection of the line to Bad Munster am Stein happened against the background that the Palatinate Railway (Pfalzbahn), which had absorbed the Palatine Northern Railway Company in 1870, wanted to compete with the Prussian Nahe Valley Railway. So the Glan Valley Railway ran from Odernheim on the right bank of the Nahe river almost parallel with the Nahe Valley Railway on the other side of the river. The Nahe Valley Railway had a significantly higher volume of traffic and the section of the Glan Valley Railway between Odernheim and Bad Münster was only important as a military railway.[10]

On 1 January 1909, the Glan Valley Railway was absorbed into the Royal Bavarian State Railways, along with the other railway lines in the Palatinate.

During the First World War, the line served largely strategic purposes as planned. Already from 9 to 16 August 1914, the Glan Valley Railway was used by several military trains daily from the Poznań (then German Posen) region to the west. The timetable was changed eight times that year. At the same time, the provision for civilian traffic during the four years of war was limited. On 1 November 1917, the stations in Eschenau, Wiesweiler and Raumbach had to be temporarily abandoned due to lack of staff, but they had already been reactivated in October 1918.[11]

Weimar Republic (1919–1933)

In the postwar period, the line was affected by damage as a result of the war, especially in the form of long travel times. In 1920, the Glan Valley Railway between Homburg and Jägersburg became part of the newly created Saar, which was controlled by the United Kingdom and France for a period of 15 years as a League of Nations mandate. This meant that Waldmohr station had customs and border controls. With the founding of Deutsche Reichsbahn in the same year, it took over the Glan Valley Railway to Schönenberg-Kübelberg and the Saar Railway (Saareisenbahn) was responsible for the remaining section to Homburg.[12]

Under the Versailles Treaty, the 1922 Conference of Ambassadors of the Allies demanded the dismantling of the Odernheim–Staudernheim line and the dismantling of one track on the remaining Glan Valley Railway. This provoked local resistance. Seven years later the German government agreed that only the Odernheim–Bad Münster section would be reduced to a single track and the Glan Valley Railway would still retain the status of a main line. It was also determined that the work would be completed within nine months from 1 September 1929 and accordingly work started on 12 November 1929, but this had no impact on the railway.[13]

In 1923 and 1924, so-called Regiebetrieb ("directed operation" of the railways by the Allied military during the Occupation of the Ruhr) was imposed under the control of France, which had occupied the Palatinate. The local population boycotted the railway during the occupation. Therefore, reinforced German Post Office bus routes and private trucks were used as an alternative to the French-controlled railways. In addition, the German Ministry of Transport refused to cooperate with the occupiers in the operation of the railway, so the French took rail operations into their own hands. Since the military officers involved did not fully understand the German operating instructions and the safe-working systems, railway operation during this time were hazardous.[14]

Third Reich and the Second World War (1933–1945)

After the reunification of the Saar with Germany in 1935 following a referendum, the customs controls between Jägersburg and Schönenberg-Kübelberg were removed. Two years later, the Reichsbahndirektion (railway administration) of Ludwigshafen, to which the Glan Valley Railway had belonged, was dissolved. From Homburg to Altenglan, the line was controlled by the Reichsbahndirektion Saarbrücken and further north it was controlled by the Reichsbahndirektion Mainz. At the same time, the track master's office (Bahnmeisterei) in Altenglan was dissolved.[15]

In 1938, the second track was restored in preparation for the Second World War. The construction of the Siegfried Line (Westwall) and the transport of troops gave the railway line an important role during the whole course of the war. Between 24 and 27 September 1938, a military exercise was held in the Palatinate. Troop trains from Frankfurt were despatched to the stations of Altenglan, Bedesbach-Patersbach, Glan-Münchweiler, Lauterecken-Grumbach and Schönenberg-Kübelberg.[15]

With the outbreak of the Second World War, rail services were restricted again. Due to its strategic importance, the line was often the target of Allied air raids that destroyed, among other things, the engine shed in Lauterecken and Offenbach station. In the last months of the war, a connecting curve was constructed between Rammelsbach and Bedesbach in the current location of Altenglan to the north of the station. This was established as a possible detour in conjunction with the Türkismühle–Kusel railway opened in 1936 as an extension of the Landstuhl–Kusel railway in case the Nahe Valley Railway between Ottweiler and Bad Münster became blocked. In fact, however, it was only used once and dismantled immediately after the end of the war.[16]

Despite these attacks, the Glan Valley Railway in 1945 had suffered less damage than any other line between the Rhine and the Saarland, so it was used by many American military trains in 1945.[17]

Post-war period (1945–1960)

Homburg and Jägersburg were included in the modern Saarland, which was separated again after the Second World War from the rest of Germany, so the stations of Jägersburg and Schönenberg-Kübelberg became customs stations again. The Homburg–Jägersburg section became part of the Saarland Railways (Saarländischen Eisenbahnen, SEB), and from 1951 the Railways of the Saarland (Eisenbahnen des Saarlandes, EdS), while the remaining part of the line was taken over by the Operations Association of the Southwest German Railways (Betriebsvereinigung der Südwestdeutschen Eisenbahnen, SWDE) until 1949, when Deutsche Bundesbahn (DB) was founded.

Already in 1945, the second track between Homburg and Jägersburg had been disconnected because it was no longer required for operational reasons and the rails could be used to repair other lines. The timetable for those sections that had been built as a strategic railway were continually thinned after the Second World War. Most notably, the Homburg–Glan-Münchweiler section was operated by a few pairs of trains that only served workers employed in the Saarland. The Glan Valley Railway at this time was the least used two-track line in southwestern Germany. The renewed separation of the Saar also led to traffic continuously declining on the Homburg–Glan-Münchweiler section of the line. The reason for this was that most of this line was in the newly created Rhineland-Palatinate and most traffic to the new state was concentrated towards Kaiserslautern. These structural changes had the effect, among other things, that the Homburg–Jägersburg section was officially listed as only a secondary line from 2 May 1955.[18]

The economic reintegration of the Saarland in Germany meant that customs controls in Schönenberg-Kübelberg were abolished in 1959, but starting in the 1950s, there continued to be further reductions in the capacity of the route. So Jägersburg station was closed for passenger by the Saarland administration in 1956 and the second track between Jägersburg and Schönenberg-Kübelberg was dismantled in 1960 because it was no longer used.[18]

Gradual closure (1960–2000)

The decline of the line in the 1960s resulted in the gradual closure of the Glan Valley Railway. It began in October 1961 with the closure of the Odernheim–Bad Münster am Stein section, with operations continuing only between Bad Münster and the connection to the Niedernhausen power station. Operations ended on the section between Odernheim and the turnoff to the power station, but the tracks were maintained in their original condition until the 1980s. In addition, the second track was also gradually removed from the remaining parts of the line from the 1960s.

In the following period the failure of DB to carry out additional rationalisation called into question the economics of the Glan Valley Railway because signalling and level crossing barriers still had to be operated manually and the safe-working systems still predominantly dated from the early days of the line.[10][19]

In 1977, weekend services ended on the Homburg–Glan-Münchweiler and the Altenglan–Staudernheim sections. On 30 May 1981, the last passenger train ran on the Homburg–Glan-Münchweiler section. Freight traffic had previously ended between Schönenberg-Kübelberg and Glan-Münchweiler. Traffic was discontinued between Altenglan and Lauterecken-Grumbach four years later and on the northern section to Staudernheim in 1986. The transport of freight between Waldmohr and Schönenberg-Kübelberg ended on 1 July 1989. In the same year, the section between Glan-Münchweiler and Altenglan was reduced to one track.

The section from Bad Münster to the Niedernhausen power station was used for both freight operations and occasional special passenger trips until late 1990 when it was closed. Since 1993, the route from Bad Münster to the former Duchroth station has been used as a cycle path. Freight traffic finally ended between Lauterecken and Meisenheim on 1 March 1993. Two years later freight traffic ended between Homburg and Waldmohr. The Lauterecken-Grumbach–Staudernheim section was officially closed in 1996.

Current developments (since 2000)

The only part of the former Homburg–Bad Münster strategic railway that is still in operation is the Glan-Münchweiler–Altenglan section of the original Landstuhl–Kusel line. This is operated by Regionalbahn services. Students of the Kaiserslautern University of Technology proposed the establishment of a draisine operation on the Altenglan–Staudernhein section of the line to prevent its final closure and the dismantling of its track. The supporters of this project included a councillor of Kusel district, Winfried Hirschberg. After an examination of the draisine lines in Templin in Brandenburg—at that time the only one in Germany—and near Magnières in Lorraine, detailed planning began, which was implemented in 2000.[20] In its first year of operation, the project had 7,300 users. This was significantly higher than expected.

The Waldmohr–Glan-Münchweiler and Odernheim am Glan–Bad Münster sections are now dismantled. On the Waldmohr–Glan-Münchweiler section and on much of the route of the dismantled second track between Odernheim and Glan-Münchweiler, the Glan-Blies Way cycling and hiking trail was built from 2001 to 2006.[21] A new tunnel was built between Schönenberg-Kübelberg and Elschbach to take the trail under state road 356.

Route

The southern section from Homburg to Glan-Münchweiler branches off the Mannheim–Saarbrücken line and initially runs through the Bruch country. The line crosses the vast Jägersburger Wald (Jägersburg forest) and touches Waldmohr and Schönenberg-Kübelberg, which is located on the northern edge of the Peterswald (forest). A few kilometres later the line reaches the Glan valley, which the line now follows to Odernheim. Between Homburg and Glan-Munchweiler the line crosses the Glan river four times because of the large meanders in its upper reaches and one of its loops is shortened by the Elschbach tunnel. After Lauterecken, the river valley widens considerably, so there are fewer bridges. Shortly before Meisenheim, the Glan Valley Railway runs through Meisenheim tunnel.

The line forks at Odernheim. A branch opened in 1897, which still exists, runs in a wide arc and ends near the Disibodenberg in Staudernheim. The southern branch, which was built for strategic reasons and is now dismantled, passed through the Kinnsfels tunnel to the Nahe valley near the Gangelsberg (mountain) and passes on the right bank of the Nahe parallel to the Nahe Valley Railway, which ran on the other side, and reaches Bad Münster by a bridge over the river.

In terms of landscape, most of the line from Schönenberg-Kübelberg to Odernheim runs through the North Palatine Uplands, where it has been dismantled between Waldmohr and Glan-Münchweiler. The northern part of the line between Odernheim and Bad Münster then runs through the Naheland.

From Homburg to Jägersburg the railway runs through the, Saar-Palatinate district of the Saarland. With the exception of Elschbach which is part of the district of Kaiserslautern, the line to Odenbach then runs through the Kusel district. The northern part between Meisenheim and Staudernheim or Bad Münster am Stein respectively is located in the district of Bad Kreuznach.

Characteristics

The Glan Valley Railway almost continuously loses height as it runs to the north, only between Homburg and Jägersburg and between Odernheim and Staudernheim are there slight climbs to the north. Between Schönenberg-Kübelberg and Glan-Munchweiler the ruling gradient was 1:100, the remaining gradient ranged from 1:144 (between Jägersburg and Schönenberg-Kübelberg) and 1:1143 (between Bedesbach-Patersbach and Ulmet).[22]

Despite the sparse population of the region, the line had a high density of stations. This was the main reason for the low passenger volumes at each station, which ultimately led to the closure of sections.

Chainage

Since the Glan-Münchweiler–Altenglan section originated as part of the Landstuhl–Kusel line and the Lauterecken–Staudernheim section was originally a continuation of the Lauter Valley Railway, the two sections originally had the chainages of those lines, so that their zero chainage points were at Landstuhl or Kaiserslautern respectively.[23]

After the opening of the strategic line in 1904, a continuous chainage was introduced starting in the west from Scheidt and running over the line to Rohrbach, which was completed in 1879 and 1895, and continuing to Homburg over the line via Kirkel and Limbach, which was opened on 1 January 1904 and then transferred to the Glan Valley Railway. As a result, the chainage of Bad Münster am Stein station was set at 109.7 km. The Odernheim–Staudernheim section originally had a separate chainage, but was it later given a chainage that continued on from the chainage between Scheidt and Odernheim. The chainage of the endpoint of the line at Staudernheim was set at km 96.9.[1][24][25]

Since the Scheidt–Homburg section was part of the shortest connection between Saarbrücken and Homburg, it became part of the Mannheim–Saarbrücken line and later a new chainage was established for the Glan Valley Railway as far as Altenglan with the zero point at Homburg. North of Altenglan station the old chainage from Scheidt was maintained, so that there is a jump from 33.1 km to 56.9 km at Altenglan.[1][25]

References

Footnotes

- Railway Atlas 2017, pp. 84–5.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 7ff.

- Sturm 2005, p. 234.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 16.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 17f.

- Sturm 2005, pp. 234f.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 22.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 36.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 21ff.

- Sturm 2005, p. 236.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 38f.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 39.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 42ff.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 43.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 49.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 50.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 52.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 54f.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 60.

- Engbarth 2007, p. 101.

- "Bahntrassenradeln – Details – Deutschland > Rheinland-Pfalz > südl. der Nahe - RP 3.08 Glan-Blies-Radweg: Abschnitt Staudernheim – Waldmohr" (in German). achim-bartoschek.de. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Emich & Becker 1996, pp. 70f.

- Emich & Becker 1996, p. 21.

- Map of the Reichsbahndirektion Mainz of 1 January 1940

- Fiegenbaum & Klee 1997, p. 420.

Sources

- Emich, Hans-Joachim; Becker, Rolf (1996). Die Eisenbahnen an Glan und Lauter [The railways on the Glan and the Lauter] (in German). Waldmohr: self-published. p. 55. ISBN 978-3980491907.

- Engbarth, Fritz (2007). "Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan – 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (2007)" (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF; 6.2 MB) on 13 December 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Fiegenbaum, Wolfgang; Klee, Wolfgang (1997). Abschied von der Schiene. Stillgelegte Bahnstrecken von 1980–1990 (in German). Stuttgart: Transpress Verlag. pp. 207–209 and 417–420. ISBN 3-613-71073-0.

- Sturm, Heinz (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen [The Palatine Railways] (in German). Ludwigshafen am Rhein: pro MESSAGE. ISBN 3-934845-26-6.

- Eisenbahnatlas Deutschland [German railway atlas]. Schweers + Wall. 2017. ISBN 978-3-89494-146-8.

External links

- "Information on the line" (in German). Michael Strauß. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "Information on the line" (in German). Markus Göttert and Marcus Ruch. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "Information on the line" (in German). Fritz Engbarth. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Lothar Brill. "Information on the line" (in German). Tunnelportale. Retrieved 15 May 2013.