Girard Desargues

Girard Desargues (French: [dezaʁɡ]; 21 February 1591 – September 1661) was a French mathematician and engineer, who is considered one of the founders of projective geometry.[1] Desargues' theorem, the Desargues graph, and the crater Desargues on the Moon are named in his honour.

Born in Lyon, Desargues came from a family devoted to service to the French crown. His father was a royal notary, an investigating commissioner of the Seneschal's court in Lyon (1574), the collector of the tithes on ecclesiastical revenues for the city of Lyon (1583) and for the diocese of Lyon.

Girard Desargues worked as an architect from 1645. Prior to that, he had worked as a tutor and may have served as an engineer and technical consultant in the entourage of Richelieu.

As an architect, Desargues planned several private and public buildings in Paris and Lyon. As an engineer, he designed a system for raising water that he installed near Paris. It was based on the use of the at the time unrecognized principle of the epicycloidal wheel.

His research on perspective and geometrical projections can be seen as a culmination of centuries of scientific inquiry across the classical epoch in optics that stretched from al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) to Johannes Kepler, and going beyond a mere synthesis of these traditions with Renaissance perspective theories and practices.[2]

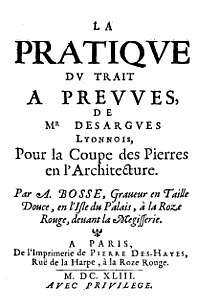

His work was rediscovered and republished in 1864. A collection of his works was published in 1951,[3] and the 1864 compilation remains in print.[4] One notable work, often cited by others in mathematics, is "Rough draft for an essay on the results of taking plane sections of a cone" (1639).

Late in his life, Desargues published a paper with the cryptic title of DALG. The most common theory about what this stands for is Des Argues, Lyonnais, Géometre (proposed by Henri Brocard).

He died in Lyon.

See also

- Desarguesian plane, non-Desarguesian plane

- Desargues' theorem

- Desargues graph

- Desargues configuration

- Desargues (crater)

- Perspective (graphical) / Perspective (visual)

- Optics

References

- Swinden, B.A. "Geometry and Girard Desargues". The Mathematical Gazette. Vol. 34, No. 310 (Dec., 1950) p. 253

- El-Bizri, Nader (2010). "Classical Optics and the Perspectiva Traditions Leading to the Renaissance". In Hendrix, John Shannon; Carman, Charles H. (eds.). Renaissance Theories of Vision (Visual Culture in Early Modernity). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. pp. 11–30. ISBN 1-409400-24-7.; El-Bizri, Nader (2014). "Seeing Reality in Perspective: 'The Art of Optics' and the 'Science of Painting'". In Lupacchini, Rossella; Angelini, Annarita (eds.). The Art of Science: From Perspective Drawing to Quantum Randomness. Doredrecht: Springer. pp. 25–47.; El-Bizri, Nader (2016). "Desargues' oeuvres: On perspective, optics and conics". In Cairns, Graham (ed.). Visioning Technologies: The Architectures of Sight. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 36–51.

- Desargues, Girard (1951). Taton, René (ed.). L'oeuvre mathématique de G. Desargues: Textes publiés et commentés avec une introd. biograph. et historique. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

- Desargues, Girard (2011). Poudra, Noël Germinal (ed.). Oeuvres de Desargues. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1108032583.

- J. V. Field & J. J. Gray (1987) The Geometrical Work of Girard Desargues, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-96403-7 .

- René Taton (1962) Sur la naissance de Girard Desargues., Revue d'histoire des sciences et de leurs applications Tome 15 n°2. pp. 165–166.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Girard Desargues |