Giovanni Baptista Ferrari

Giovanni Baptista (also Battista) Ferrari (1584 in Siena – 1 February 1655 in Siena), was an Italian Jesuit and professor in Rome, a botanist, and an author of illustrated botanical books and a Syriac-Latin dictionary.

| Part of a series on the |

| Society of Jesus |

|---|

Christogram of the Jesuits |

| History |

| Hierarchy |

| Spirituality |

| Works |

| Notable Jesuits |

|

|

Biography

Giovanni Baptista Ferrari was born to an affluent Sienese family and entered the Jesuit Order in Rome in 1602. Ferrari was linguistically highly gifted and an able scientist, who, at 21 years of age, knew a good deal of Hebrew and spoke and wrote excellent Greek and Latin. He became a professor of Hebrew and Rhetoric at the Jesuit College in Rome and in 1622 was editor of a Syriac-Latin dictionary (Nomenclator Syriacus).[1]

De Florum Cultura

Ferrari devoted himself till 1632 to the study and cultivation of ornamental plants, and published De Florum Cultura, which was illustrated with copperplates by, amongst others, Anna Maria Vaiani, possibly the first female copper-engraver. The first book deals with the design and maintenance of the garden and garden equipment. The second book provides descriptions of the different flowers, while the third book deals with the culture of these flowers. The fourth book, continues with a treatise on the use and beauty of the flower species, including their different varieties and mutations.

Through his acquaintance with Cassiano dal Pozzo, secretary of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, he was appointed to manage the new garden at the Barberini Palace. The plants featured in Ferrari's research came from Cardinal Francesco Barberini's private botanical garden, the Horti Barberini, a garden which was under the care of Ferrari.

The first edition of his de florum publication was dedicated to Barberini and the second was dedicated to Barberini's sister-in-law, Anna Colonna.[2] Ferrari became horticultural advisor to the Pope.[1]

''Hesperides sive de Malorum...

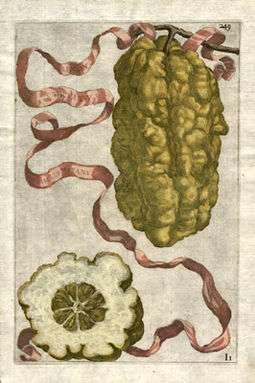

Another work is the Hesperides sive de Malorum Aureorum Cultura et Usu Libri Quatuor, first published in 1646. Ferrari's close relationship with Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588-1657), a noted scholar and student of citrus, led to the creation of this work. The first volume of this work is devoted to citrus and its many varieties and variations.

The plates were produced by the best artists of the time, such as Johann Friedrich Greuter, Cornelis Bloemaert and Nicolas Joseph Foucault. Plates were also prepared by the renowned painters and draughtsmen of Roman Baroque, such as Pietro da Cortona, Andrea Sacchi, Nicolas Poussin, Pietro Paolo Ubaldini, F. Perier, Francesco Albani, Filippo Gagliardi, G.F. Romanelli, Guido Reni, Domenico Zampieri and H. Rinaldi. The plates show life-sized whole fruit, including sections. Other plates show Hercules, mythological scenes, garden buildings, Orangeries, garden tools, etc.. He published this at a time growing interest in and structural sophistication of seventeenth-century orangeries, constructed needed to protected citrus trees from the cold of Northern Europe or heat of Italian summers.[3]

Both works are important as they display accurate representations.

Ferrari was the first scientist to provide a complete description of the limes, lemons and pomegranates. He also described medical preparations, the details on citron and prescribed limes, lemons and pomegranates as medicinal plants against scurvy.

Works

- Ferrari, Giovanni Battista (1622). Nomenclator syriacus Io. Baptistae Ferrarii Senensis e Societate Iesu (in Latin). Stefano Paolini.

- Hesperides siue de malorum aureorum cultura et vsu Libri quator Io. Baptistae Ferrarii Senensis e Societate Iesu, Romae: Sumptibus Hermanni Scheus, 1646

- In funere Marsilij Cagnati medici praestantissimi laudatio Ioannis Baptistae Ferrarij Senensis e Societate Iesu: habita in aede S. Mariae in Aquiro 5. Kal. Augusti 1612, Romae: apud Iacobum Mascardum, 1612.

- Io. Bapt. Ferrarii ... De florum cultura libri 4, Romae: excudebat Stephanus Paulinus, 1633.

- Io. Bapt. Ferrarii Senen. Societatis Iesu Orationes, Lugduni: sumptibus Ludouici Prost, haeredis Rouille, 1625.

- Io. Bapt. Ferrarii Senensis ... Orationes, Venetiis: apud Beleonium, 1644.

- Io. Bapt. Ferrarii Senensis e Soc. Iesu Orationes, Romae: apud Franc. Corbellettum, 1627.

- Io. Bapt. Ferrarii Senensis e Societate Iesu Orationes quartum recognitae et auctae, (Romae: typis Petri Antonij Facciotti, 1635).

- Io. Baptistae Ferrarii senensis ... Orationes, Mediolani: apud haer. Pacifici Pontij, & Io. Baptistam Piccaleum, impressores archiepiscopales, 1627.

- Ioh. Bapt. Ferrarii Senensis e Societ. Iesu Orationes, Nouissima editio iuxta exemplar, Coloniae: apud Cornel. Egmont, imprim. 1634.

- Joh: Baptistae Ferrarii Senensi, S.I. Flora, seu De florum cultura lib. 4, Editio nova. Accurante Bernh Rottendorffio, Amstelodami: prostant apud Joannem Janssonium, 1664.

- Joh: Bptistae Ferrarii Senensi, S.I. Flora, seu de florum cultura lib. 4, Editio nova. Accurante Bernh Rottendorffio ..., Amstelodami: Prostant apud Joannem Janssonium, 1664.

References

- Erickson, Robert F., "Giovanni Battista Ferrari", Missouri Botanical Garden

- Fountains, statues, and flowers: studies in Italian gardens of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by Elisabeth B. MacDougall (Dumbarton Oaks, 1994)

- "Hesperides sive de Malorum Aureorum cultura et usu", The Metropolitan Museum of Art

External Links

- Gardening Knife, from "Hesperides" by Giovanni Battista Ferrari

- Ferrari's book

- Antique Prints

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110719182236/http://www.artfact.com/catalog/viewLot.cfm?lotCode=IrAgEt8i

- https://ssl.kundenserver.de/maps-n-views.com/dekorative/deko_gross/dc2596_e.htm%5B%5D

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080123181338/http://www.georgeglazer.com/prints/nathist/botanical/ferraricit/ferraricit.html

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giovanni Battista Ferrari. |