Georgia Experiment

The Georgia Experiment was the colonial-era policy prohibiting the ownership of slaves in the Georgia Colony. At the urging of Georgia's proprietor, General James Oglethorpe, and his fellow colonial trustees, the British Parliament formally codified prohibition in 1735, two years after the colony's founding. The ban remained in effect until 1751, when the diminution of the Spanish threat and economic pressure from Georgia's emergent planter class forced Parliament to reverse itself.

James Oglethorpe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor of Georgia | |

| In office 1732–1743 | |

| Prime Minister | Sir Robert Walpole |

| Preceded by | No Office created |

| Succeeded by | William Stephens |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 December 1696 Surrey, England |

| Died | 30 June 1785 (aged 88) Cranham, Essex, Great Britain |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth (née Wright) |

| Alma mater | Eton College, Corpus Christi, Oxford, a military academy, Paris, France |

| Profession | Statesman, soldier, agriculturalist, philanthropist |

Background

Having envisioned the Georgia colony as a haven for debtors and reformed prisoners, Oglethorpe was uncomfortable with the prospect of Georgians attaining immense wealth and coalescing into a planter aristocracy (akin to that across the border in South Carolina) through the exploitation of slave labor.[1] Oglethorpe shared his preference for an austere ethic of hard work with his fellow trustees of the colony, who believed that their preeminent social goal – moral reform through individual economic autonomy – would be undermined by the introduction of slavery.

The ban on slavery had practical military implications as well. During the mid 18th century, the Spanish maintained a foothold in North America through their colonial presence in Florida, which borders Georgia to the south. London envisioned Georgia as a buffer colony to stem Spanish expansion in the Southeast and protect the more profitable colonies to the north.[2]

The Spanish tactic of recruiting American slaves to military service in exchange for their emancipation buoyed Oglethorpe's experiment by providing a strategic incentive to minimize the slave presence in Georgia.[3]

Implementation

Believing that the anticipated agricultural output of Georgia – mostly low-labor intensity products such as silk – will lend itself better to small-scale farming by white Europeans, the trustees expected the early colonist to acquiesce their vision of the colony free of slave labor. Yet Oglethorpe underestimated the colonists' disinclination toward the intensive labor requisite for agricultural output, especially by comparison to their much wealthier and far more leisurely counterparts in South Carolina.[4] In addition, in the interest of furthering their holdings into George’s plentiful farmland, some South Carolinian plantation owners lobbied Georgians to flout the trustees' wishes.[5]

Sensing that he could not hold the ban in place through sheer force of will, Oglethorpe sought and received Parliamentary backing when the House of Commons passed legislation codifying the prohibition on slavery in Georgia in 1735.

Resistance

The fiercest opponents of the Georgia Experiment were a group known as the Malcontents, led by Patrick Tailfer and Thomas Stephens.[6] Unlike those rescued from the English debtors' prison for the colonial proprietors, the Malcontents were overwhelmingly Scottish and received no financial assistance from the trustees to aid their relocation to Georgia.[7] Stephens and Tailfer organized numerous publications and letter-writing campaigns, the most prominent which netted some 121 signatures in 1738.[8] When Oglethorpe and the trustees proved recalcitrant in the face of this public pressure, the Malcontents lobbied the House of Commons directly, including junkets by the leadership to London.[9] However, Parliament was unmoved by their arguments so long as Spain remained of military threat to the British colonies.

| Battle of Bloody Marsh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of Jenkins' Ear & Invasion of Georgia | |||||||

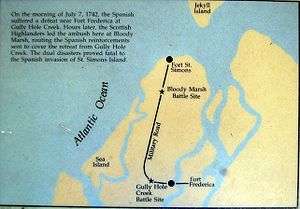

A Map of the Bloody Marsh area as it was in 1742 (North is down) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 650 soldiers, militia and native Indians[10] | 150–200 soldiers[11] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | 200 killed [12][13] | ||||||

Repeal

In 1742, Oglethorpe won a resounding victory over the Spanish of the Battle of Bloody Marsh, effectively ending Spanish expansionism in North America. It was Oglethorpe's greatest military victory that sealed the fate of his prized Georgia Experiment, as the removal of the Spanish threats substantially decreased incentive for the House of Commons to continue the promulgation of an increasingly unpopular ban on slavery. By 1750, the trustees acquiesced to Georgia's demand for slave labor[14] and in that year Parliament revised the act of 1735 to allow slavery as of January 1, 1751.[15]

Aftermath

Once the Georgia experiment was formally abandoned, the colony quickly caught up to the regional neighbors in the acquisition of slaves. A decade after the repeal, Georgia boasted one slave for every two freemen, and slaves made up about one-half of the colony's population on the eve of the American Revolution.[16] By virtue of increased production of staple products (particularly rice and indigo) as a result of the importation of slave labor, Georgia had the economic luxury to support a dramatically growing population: between 1751 and 1776, the colony's population increase more than tenfold, to a total of about 33,000 (including 15,000 slaves).[16]

However, not all white Georgians were unambiguous beneficiaries. Low–skilled white labor and white artisans commanded drastically reduced wages due to the competition of slave labor.[17] The growing chasm between the ascendant planter class and a large contingent of small farmers, independent artisans, and unskilled white laborers sharply factionalized the colony both before and during the Revolutionary War. Georgia's lackluster performance in the war effort has been linked to the uncertain leadership of this comparatively new and rootless aristocracy.[18]

Notes

- Bartley (1983), pp. 2–3

- Bartley (1983), p. 2

- Gray & Wood (1976), p. 365

- Wood (1984), pp. 16–17

- Wood (1984), pp. 17–18

- Wood (1984), p. 38

- Bartley (1983), p. 4

- Wood (1984), p. 29

- Wood (1984), p. 40

- Marley p. 261

- Marley p. 262

- Brooks (1972), p. 77

- Brevard & Bennett (1904), p. 75

- Wood (1984), p. 82

- Wood (1984), p. 83

- Bartley (1983), p. 5

- Davis (1976), p. 98

- Bartley (1983), p. 7

References

- Bartley, Numan V. (1983). The Creation of Modern Georgia. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820306681.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brevard, Caroline Mays; Bennett, Henry Eastman (1904). A History of Florida. Cincinnati, OH: American Book Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brooks, Robert Preston (1972). History of Georgia. Boston, MA: Atkinson, Mentzer, and Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Harold E. (1976). The Fledgling Province: Social and Cultural Life in Colonial Georgia, 1733–1776. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Ralph; Wood, Betty (1976). "The transition from indentured to involuntary servitude in colonial Georgia". Explorations in Economic History. 13 (4): 353–370. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(76)90013-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wood, Betty (1984). Slavery in Colonial Georgia (1730–1755). Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)