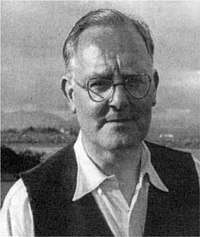

George William Lyttelton

The Hon George William Lyttelton (6 January 1883 – 1 May 1962) was a British teacher and littérateur from the Lyttelton family. Known in his lifetime as an inspiring teacher of classics and English literature at Eton, and an avid sportsman and sports writer, he became known to a wider audience with the posthumous publication of his letters, which became a literary success in the 1970s and 80s, and eventually ran to six volumes.

Early life

Lyttelton was born at Hagley Hall in Worcestershire, the second son of Charles Lyttelton, 5th Baron Lyttelton and later 8th Viscount Cobham, and Mary Susan Caroline Cavendish (second daughter of the 2nd Baron Chesham). He was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge. He was a sporting young man, distinguishing himself at the Eton field game (a form of football),[1] and at cricket, in which he shared a second wicket partnership of 476 for A. C. Benson's XI v H. V. Macnaghten's XI (Eton, 1901), and played at Lord's in the Eton v Harrow matches of 1900 and 1901.[2]

At Trinity, Lyttelton was a distinguished shot put competitor, winning the event for Cambridge v Oxford three years in a row (1904, 37'7"; 1905, 37'11" and 1906, 38'3¾").[3][4] He was a less distinguished amateur musician: according to a contemporary university magazine: "When George Lyttelton practises the cello, all the cats in the district converge upon his rooms in the belief that one of their members is in distress."[5] He was a member of the University Pitt Club and was its librarian.[6]

Adult life

After graduation he returned as a master to Eton, where his uncle Edward Lyttelton was headmaster from 1905 to 1916. He married Pamela Marie Adeane, daughter of Charles Robert Whorwood Adeane and Madeline Pamela Constance Blanche Wyndham, on 3 April 1919. They had four daughters and one son – the latter being the jazz trumpeter and radio presenter Humphrey Lyttelton. His second daughter Helena married the Eton master Peter Lawrence.[7] His grandson through his eldest daughter Diana is Henry Hood, 8th Viscount Hood, who served as Lord-in-waiting to the Queen.[8]

Lyttelton retired in 1945, having taught at Eton for his entire career. He taught, among others, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, Cyril Connolly, J. B. S. Haldane, and John Bayley. Lyttelton taught mostly classics in the fifth form, but became known for his optional course of English as "extra studies" for senior specialists.[9] The biographer Philip Ziegler said of him:

- George Lyttelton was one of the greatest of English schoolmasters. He was wise and tolerant; his massive presence ensured a dignity which his fine sense of the ridiculous alleviated without diminishing; he cared passionately about good writing and communicated that passion to his pupils.[10]

Another former pupil wrote:

- From that study we staggered with our arms full of books, Wells and Hemingway, Milton and Dr Johnson, Henry James and George Moore, our minds fired by his enthusiasm and wise advice, our shoulders tingling from the squeeze of his mighty hand as he guided us through the bookshelves. We think of him... majestically immobile as he umpired in the Field, and he was the best of them all in ruling the game and in writing about it afterwards; or... those brilliant expositions of the reading or writing of English where he achieved the perfect artistry of teaching; or at his Old Boy dinners, enveloped in a vast and aging dinner-jacket, delivering with commendable timing a string of improbable stories about his large family or the more obscure annals of Suffolk agricultural life.[11]

Lyttelton was a member of the Johnson Club and The Literary Society in London, and of the Marylebone Cricket Club.[12] Between the wars, he contributed The Times's reports on the Eton and Harrow matches, usually anonymously, but in 1929 on the occasion of the hundredth match his tour d'horizon of the series appeared under his name.[13] His reports were later described in The Times as the best prose of their time.[14]

In 1945 Lyttelton retired from Eton and moved to Grundisburgh, Suffolk, where he died at the age of 79.[9]

Legacy

Lyttelton co-edited an anthology, An Eton Poetry Book (1925), which was well received,[15] but his life would not have come to the notice of the wider world were it not for his weekly correspondence with a former pupil, Rupert Hart-Davis, which lasted from 1955 until Lyttelton's death in 1962. This correspondence, published after Lyttelton's death as The Lyttelton/Hart-Davis Letters, was an immediate literary success and eventually ran to six volumes. Reviewers contrasted Hart-Davis's weekly accounts of a busy urban life with Lyttelton's detached, and often humorous, observations from his retirement in Suffolk.[10] The Daily Telegraph said of them: "In a hundred years' time, I suspect, the letters will be read with as much pleasure as they are today.... This is a book one could go on quoting forever."

In 2002 Lyttelton's commonplace book was edited and published, confirming how broad his literary interests were, ranging from Greek and Latin classics to quirky advertisements and press cuttings – not all of them fit for publication, as his son Humphrey makes clear in the foreword to the commonplace book.[16]

Notes

- The Times, 1 December 1900, p. 9

- Cricinfo and The Times, 14 July 1990, p. 14 and 12 July 1901, p. 11

- The Times, 28 March 1904, p. 11

- Achilles.org

- Lyttelton, p. 57

- Fletcher, p. 94

- Lawrence baronets, of Ealing Park (1867)

- Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage: 107th Edition. 2. Burke's Peerage. 2003. p. 1955.

- Hart-Davis, p. ix

- The Times, 8 June 1978, p. 12

- The Times, 11 May 1962, p. 19

- Hart-Davis passim

- The Times, 12 June 1929, p. 15

- The Times, 2 May 1962, p. 16

- "New Books", The Manchester Guardian, 18 June 1925, p. 7

- Ramsden, p. 8

References

- Fletcher, Walter Morley (2011) [1935]. The University Pitt Club: 1835-1935. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107600065.

- Hart-Davis, Rupert (ed) (1985). The Lyttelton/Hart-Davis Letters. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-4246-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Lyttelton, Humphrey (2007). It Just Occurred to Me: the reminiscences and thoughts of Chairman Humph. London: Robson. ISBN 1905798172.

- Ramsden, George (ed) (2002). George Lyttelton's Commonplace Book. York: Stone Trough Books. ISBN 095295348X.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)