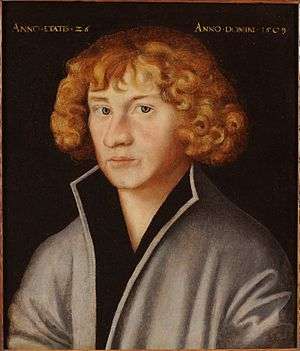

George Spalatin

Georg(e) Spalatin was the pseudonym taken by Georg Burkhardt (17 January 1484 – 16 January 1545), was a German humanist, theologian, reformer, secretary of the Saxon Elector Frederick the Wise, as well as an important figure in the history of the Reformation.

Biography

Burkhardt was born at Spalt (from which he took the Latinized name "Spalatinus"), near Nuremberg, where his father was a tanner. He went to Nuremberg for his education when he was thirteen years of age, and soon afterwards to the University of Erfurt, where he received his bachelor's degree in 1499. There he attracted the notice of Nikolaus Marschalk, the most influential professor, who made Spalatin his amanuensis and took him to the new University of Wittenberg in 1502. Here he lived in quarters on Schlossplatz just east of Schlosskirche, Wittenberg.[1]

In 1505 Spalatin returned to Erfurt to study jurisprudence. He was recommended to Conrad Mutianus, and was welcomed by the little band of German humanists of whom Mutianus was chief. His friend acquired a post for him as teacher of novices in the monastery at Georgenthal, and in 1508 he was ordained priest by Bishop Johann von Laasphe, who had ordained Martin Luther. In 1509 Mutianus recommended him to Frederick III the Wise, the Elector of Saxony, who employed him to act as tutor to his nephew, the future elector, John Frederick.

Spalatin speedily gained the confidence of the elector, who sent him to Wittenberg in 1511 to act as tutor to his nephews, and procured for him a canon's stall in Altenburg. In 1512 the elector made him his librarian. He was promoted to be court chaplain and secretary, and took charge of all the elector's private and public correspondence. His solid scholarship, and especially his unusual mastery of Greek, made him indispensable to the Saxon court.

Spalatin had never cared for theology, and, although a priest and a preacher, had been a humanist. How he first became acquainted with Luther is impossible to say — probably at Wittenberg — but the reformer from the first exercised a great power over him, and became his chief counsellor in all moral and religious matters. His letters to Luther have been lost, but Luther's answers remain, and are extremely interesting. There is scarcely any fact in the opening history of the Reformation which is not connected in some way with Spalatin's name. He read Luther's writings to the elector, and translated for his benefit those in Latin into German.

Spalatin accompanied Frederick to the Diet of Augsburg in 1518, and shared in the negotiations with the papal legates, Thomas Cajetan and Karl von Miltitz. He was with the elector when Charles V was chosen emperor and when he was crowned. He was with his master at the Diet of Worms. In short, he stood beside Frederick as his confidential adviser in all the troubled diplomacy of the earlier years of the Reformation. Spalatin would have dissuaded Luther again and again from publishing books or engaging in overt acts against the papacy, but when the thing was done none was so ready to translate the book or to justify the act.

On the death of Frederick the Wise in 1525, Spalatin no longer lived at the Saxon court. But he attended the imperial diets, and was the constant and valued adviser of the electors, John and John Frederick. He went into residence as canon at Altenburg, and incited the chapter to institute reforms, somewhat unsuccessfully. He married in the same year.

During the later portion of his life, from 1526 onwards, Spalatin was chiefly engaged in the visitation of churches and schools in the Electorate of Saxony, reporting on the confiscation and application of ecclesiastical revenues, and he was asked to undertake the same work for Albertine Saxony. He was also permanent visitor of Wittenberg University. Shortly before his death he fell into a state of profound melancholy, and died at Altenburg. He was buried in the vault of the St. Bartholomew church.

Works

Spalatin left behind him a large number of literary remains, both published and unpublished. His original writings are almost all historical. Perhaps the most important of them are:

- Annales Reformationis oder Jahrbücher von der Reformation Lutheri, edited by E. S. Cyprian (Leipzig, 1718)

- "Das Leben and die Zeitgeschichte Friedrichs des Weisen," published in Georg Spalatins Historischer Nachlass and Briefe, edited by Christian Gotthold Neudecker and Ludwig Preller (Jena, 1851)

A list of them may be found in Adolf Seelheim's Georg Spalatin als sächsischer Historiograph (1876).

References

- Plaque to Spalatin, Wittenberg

There is no comprehensive biography of Spalatin, as his letters have yet to be collected and edited.

- Article on Spalatin by Theodor Kolde, in Herzog-Hauck, Realencyklopädie, Bd. xviii. (1906).

- Spalatin was called upon in about 1510 by Frederick III to compile the Chronicle of Saxony and Thuringia - the 3 volumes of the Spalatin Chronik include more than 1000 miniature paintings from the workshop of Lucas Cranach.

- Höss, Irmgard, Georg Spalatin, 1488-1545 (Weimar, 1956)

- Jacobs, Henry Eyster. “Spalatin, George.” Lutheran Cyclopedia. New York: Scribner, 1899. p. 450.

External links

- Georg Spalatin letters, 1528, 1536 at Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology