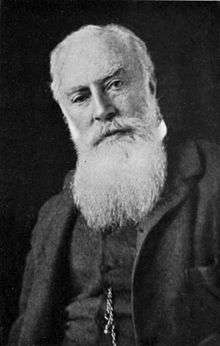

George Salting

George Salting (15 August 1835 – 12 December 1909) was an Australian-born British art collector. He had inherited considerable wealth from his father; Salting collected paintings, Chinese porcelains, furniture, and many other categories of art and decorative items. He left his paintings to the National Gallery, London, prints and drawings to the British Museum, and the remainder to the Victoria & Albert Museum, requesting that the collection be displayed intact rather than divided among the museum's departments.

George Salting | |

|---|---|

George Salting | |

| Born | 15 August 1835 Sydney |

| Died | 12 December 1909 (aged 74) London, England |

| Resting place | Brompton Cemetery |

| Occupation | Art collector |

Early life

Salting was born in Sydney, the son of Severin Knud Salting (1806–1865)[1] (in English 'Severin Kanute Salting'), a Dane who had extensive business interests in New South Wales. In 1858 he made a gift of £500 to the University of Sydney to found scholarships to be awarded to students from Sydney Grammar School.[2] George Salting's mother was Louisa Augusta, née Fiellerup.[3]

George Salting was educated locally and then moved with his family to England and studied at Eton College.[3] In 1853 the family returned to New South Wales, and Salting entered the newly founded University of Sydney.[3] There he won prizes for compositions in Latin hexameters in 1855 and 1857, in Latin elegiacs in 1856, 1857 and 1858, and for Latin essays in 1854 and 1856. Salting graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1857. In 1858 the Salting family again travelled to England; Louisa Salting died there on 24 July 1858. Severin Salting settled in Kent, where he died in 1865.[3] Severin Salting made a large fortune in sheep-farming and sugar-growing which he bequeathed to his son; George Salting inherited a fortune estimated at £30,000 a year.[2]

Career

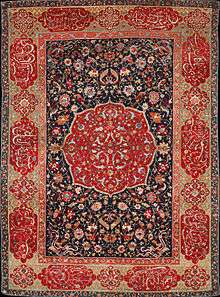

Largely influenced by the connoisseur, Louis Huth, Salting began collecting Chinese porcelain, developing a fine discriminating taste for it. His collection gradually extended and included English furniture, bronzes, majolica, glass, hard stones, manuscripts, miniatures, pictures, carpets, and other items which might be found in a good museum.[2]

Salting was a careful buyer, as a rule dealing only with two or three dealers whom he felt he could trust, though he sometimes bought at auction. He often obtained expert advice and his own knowledge was always growing. As a consequence he made few mistakes, and these were usually corrected by the pieces being exchanged for better specimens. Salting lived modestly mostly in London, occupying just two living rooms.[5] Except for an occasional few days shooting, he made collecting, and its associated research and study, his occupation.[2]

Later life

Salting never married and he did not give largely to charities. In spite of his large expenditure on collecting, his fortune increased during his lifetime.

Salting died in London and is buried in Brompton Cemetery.[2] His will was sworn at over £1,300,000. Of this he bequeathed £10,000 to London hospitals, £2000 to the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital at Sydney, and £30,000 to relatives and others. The residue of his estate went to the heirs of his brother, who predeceased him.[2]

Legacy

Salting left his entire collection of paintings, Oriental china, bronzes, and miniatures, valued at from $5,000,000 to $20,000,000, to British museums.[5] He bequeathed his paintings to the National Gallery, London, and his prints and drawings to the British Museum as the respective trustees might select. The remainder of his art collection went to the Victoria and Albert Museum, with a proviso that it was to be kept together and not distributed over the various departments. It is a notable collection to have been put together by one person, the standard being extraordinarily high. The Chinese pottery and porcelain belonged mostly to the later dynasties, but much of the work of the great T'ang period was practically unobtainable when Salting was collecting. It was suggested at the time of his death that as his wealth had been drawn from Australia, some of his collection should be donated to the Australian galleries. Nothing came of this; probably the legal difficulties were impassable.[2]

John D. Beazley named after an attic red-figure vase formerly owned by George Salting today in the Victoria and Albert Museum, Salting Painter.[6]

Collection

He gave three paintings to the National Gallery during his life, and bequeathed an additional 192 in his will. Of those 31 have since been transferred to the Tate Gallery.[7] His collection of paintings included:

- Dieric Bouts, Virgin and Child

- Robert Campin (follower), The Virgin and Child before a Firescreen

- Canaletto, Venice: The Piazza San Marco from Two Views of Piazza San Marco

- Petrus Christus, Portrait of a Young Man

- Cima da Conegliano, David and Jonathan (?) and The Virgin and Child

- Joos van Cleve, The Holy Family

- John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral and Leadenhall from the River Avon and Weymouth Bay: Bowleaze Cove and Jordon Hill

- Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, A Wagon in the Plains of Artois, The Wood Gatherer, The Leaning Tree Trunk, Evening on the Lake, Cows in a Marshy Landscape, Souvenir of a Journey to Coubron, and A Flood

- Charles-François Daubigny, River Scene with Ducks, The Garden Wall, Willows and Alders

- Gaspard Dughet, Landscape with a Cowherd

- Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of a Young Man in Red

- Jan van Goyen, A Windmill by a River, A River Scene, with Fishermen laying a Net and A Scene on the Ice

- Frans Hals, Portrait of a Woman with a Fan and Portrait of a Man holding Gloves

- Meindert Hobbema, Cottages in a Wood and A Road winding past Cottages

- Hans Memling, A Young Man at Prayer

- Gabriël Metsu, The Interior of a Smithy and An Old Woman with a Book

- Jean-François Millet, The Whisper

- Adriaen van Ostade, A Peasant holding a Jug and a Pipe, A Peasant courting an Elderly Woman and 'The Interior of an Inn

- Sebastiano del Piombo, The Daughter of Herodias

- Paulus Potter, Cattle and Sheep in a Stormy Landscape

- Francesco Raibolini, Bartolomeo Bianchini

- Théodore Rousseau, Sunset in the Auvergne

- Peter Paul Rubens, Aurora abducting Cephalus

- Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael, A Cottage and a Hayrick by a River, A Rocky Hill with Three Cottages, a Stream at its Foot, Vessels in a Fresh Breeze, A Road leading into a Wood, A Ruined Castle Gateway and An Extensive Landscape with Ruins

- Luca Signorelli, The Holy Family

- Jan Steen, Peasants merry-making outside an Inn, A Man blowing Smoke at a Drunken Woman, An Interior with a Man offering an Oyster to a Woman, Skittle Players outside an Inn, A Peasant Family at Meal-time ('Grace before Meat') and A Pedlar selling Spectacles outside a Cottage

- Johannes Vermeer, Lady Seated at a Virginal

- Andrea del Verrocchio, The Virgin and Child with Two Angels

Notes

- Taken from the grave of the father in Brompton Cemetery

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Salting, George". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- A. F. Pike, 'Salting, Severin Kanute (1805–1865)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 2, MUP, 1967, p. 415. Retrieved 6 December 2009

- "Salting Carpets And Topkapi Prayer Rugs: A Detective Story". Tea and Carpets (Blogspot). Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Obit: "George Salting", New York Times, 17 December 1909

- "George Salting". National Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Salting. |

- The Times, 14, 15, 17, 31 December 1909, 26 January 1910

- Victoria and Albert Museum Guides: The Salting Collection, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1911.

- The Sydney Herald, 20 August 1835

- The Sydney University Calendar, 1862, 1938