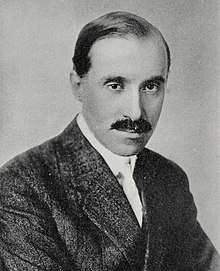

George Hamlin

George Hamlin (20 September 1869 – 20 January 1923) was an American tenor, prominent on the concert stage as a lieder and oratorio singer and later in the opera house when he sang leading tenor roles with the Philadelphia-Chicago Grand Opera Company. He also recorded extensively on the Victor label.[1][2]

George Hamlin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George John Hamlin 20 September 1869 Elgin, Illinois, USA |

| Died | 20 January 1923 (aged 53) New York City, USA |

| Occupation | Opera and concert singer (tenor) |

Life and career

Hamlin was born in Elgin Illinois to Mary (née Hart) and John Austin Hamlin. His father was a former magician who had made his fortune from Hamlin's Wizard Oil, a patent medicine sold as a cure-all under the slogan "There is no sore it will not heal, no pain it will not subdue." Shortly after Hamlin's birth, the family relocated to Chicago where his father went into the theatre business. He bought the site of Hooley's Opera House which had been destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 and built and managed what was then called the Chicago Grand Opera House. He eventually handed over its management to George's elder brothers Harry L. and Frederick R. Hamlin.[3][4][5][6]

George Hamlin was educated at Phillips Academy where he graduated in 1889 and studied singing in London with George Henschel. He made his debut in 1895 as the tenor soloist in Mendelssohn's Lobgesang performed by the St. Louis Choral Symphony Society. Over the next 16 years he performed widely in the US and Europe in solo vocal recitals and oratorios, including annual recitals in Chicago and New York City, and is credited with having introduced the art songs of Richard Strauss to American audiences. Towards the end of this period he also became a recording artist for Victor Records.[2][6][7][8]

Although Hamlin had earlier sung in concert performances of operas such as Samson and Delilah, he did not appear in staged opera until he joined the Philadelphia-Chicago Grand Opera Company in its 1911/1912 season. His friend Victor Herbert had written the leading tenor role (Lt. Paul Merrill) in his new opera Natoma for Hamlin's voice. Hamlin ultimately backed out of the world premiere in Philadelphia in February 1911, and it was sung by John McCormack instead.[9] However, the following December Hamlin sang the role in Chicago and appeared in it nine more times. One of the Philadelphia critics wrote of his February 1912 performance there:

Mr. Hamlin's voice has much to commend it in the way of smoothness and sympathy, and he sings with taste and skill, while he also carried himself well, put real feeling into his acting, and altogether made a highly favorable impression.[10]

Hamlin continued his performances in recital and oratorio but sang further leading tenor roles with the Philadelphia-Chicago company through 1917 both in Chicago and on the company's US tours. These included Pinkerton in Madame Butterfly, Gennaro in Jewels of the Madonna, Edward Plummer in Goldmark's Das Heimchen am Herd (performed in English as The Cricket on the Hearth), Don José in Carmen, Cavaradossi in Tosca, Florindo in Parelli's I dispettosi amanti, François in Madeleine, and Walter in Bucharoff's The Lover's Knot at its world premiere in 1916.[2][11][12]

In the later years of his career Hamlin also taught singing privately at his home on Madison Avenue in New York City, and at his summer home in Lake Placid, New York. In late October 1922 Frank Damrosch announced that Hamlin would be joining the faculty at the New York Institute of Musical Art in the coming year. However, earlier that month a sudden illness had caused Hamlin to cancel his performance of the Brahms Liebeslieder at the Berkshire Festival. His health continued to decline and he died at his New York City home on 20 January 1923 at the age of 53. He was survived by his wife Harriet Eldridge Hamlin whom he had married in 1892 and their three children, John, George, and Anna.[13][14][12]

Hamlin's daughter Anna (1900-1988) also became a singer after studying under Marcella Sembrich and in Italy. She performed in recitals and sang minor soprano roles with Chicago Civic Opera and later was a voice teacher at Smith College from 1939 to 1959. After her retirement she moved to New York City where she established a private vocal studio. Her students there included Judith Raskin, Claudia Lindsey, and Edna Garabedian. In 1978 she published her memoirs entitled Father Was A Tenor. The George and Anna Hamlin papers dating from 1868 to 1983 are held in the New York Public Library as is a lengthy recorded interview of Anna Hamlin conducted by the broadcaster Fred Calland in 1972. The interview alternates between reminiscences of her father and the playing of several of his recordings with detailed analysis and commentary by Calland.[15][16][17]

References

- Miller, Philip L. (2001). "Hamlin, George". The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Retrieved 18 March 2019 via Oxford Music Online (subscription required for full access).

- Kutsch, Karl-Josef and Riemens, Leo (2004). "Hamlin, George". Großes Sängerlexikon (4th edition), Vol. 4, p. 1947. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 359844088X (in German)

- Gavett, Joseph L. (2008). North Dakota: Counties, Towns & People, Part 1, pp. 62–63. Watchmaker Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 1603861157

- Young, James Harvey (1961). Chapter 12: Medicine Show. The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation, pp. 193–194. Princeton University Press. Reprint retrieved via Quackwatch 18 March 2019.

- s.n. (1883). Chicago's First Half Century, 1833-1883, pp. 51–53. Inter Ocean Publishing Company

- White, James Terry (ed.) (1924). "Hamlin, George John". The National Cyclopædia of American Biography, Vol. 19, pp. 59–60. James T. White and Company

- s.n.(3 March 1916). "George Hamlin's recital". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Kobbé, Gustav (June 1902). "Richard Strauss and His Music". The North American Review Vol. 174, No. 547, p. 794. Retrieved 18 March 2019 (subscription required).

- Gould, Neil (2011). Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life, p. 412. Oxford University Press. ISBN 082322872X

- Lahee, Henry Charles (1912). The Grand Opera Singers of To-day, p. 437, The Page Company.

- Griffel, Margaret Ross (2012). Operas in English: A Dictionary, p. 289. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810883252

- s.n. (12 January 1923). "George J. Hamlin, Tenor, Dies at 53". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- s.n. (26 October 1922). "Institute of Musical Art Faculty Additions". Musical Courier, p. 39. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Osgood, H. O. (5 October 1922). "The Berkshire Festival". Musical Courier, p. 26. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Heise, Kenan (9 June 1988). "Anna Hamlin, Singer and Voice Instructor". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- New York Public Library. "George and Anna Hamlin papers". Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- OCLC 786187688. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

Further reading

- The Musical Critic (June 1898) pp. 4, 8, 9 (contains descriptions and reviews of several concert and oratorio performances by Hamlin)

External links

- 8 remastered audio files recorded by Hamlin for Victor Records on archive.org. They include "Sally in Our Alley" by Henry Carey, "Siciliana" from Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana, and two Christian Science hymns "Saw Ye My Saviour" and "Shepherd, Show Me How to Go". (MP3 format)

- 10 audio files recorded by Hamlin for Victor Records in the Library of Congress. They include "Brindisi" from Cavalleria rusticana, "Im Kahne" by Edvard Grieg, "Lehn' deine Wang' an meine Wang'" by Adolf Jensen, and "Vien meco il ruscello" from Parelli's I dispettosi amanti. (requires Adobe Flash)

- Image of "Creleyron'", George Hamlin's summer house in Lake Placid, New York

- South Atlantic States Music Festival (1912). Official Program. Band & White