George H. Steuart (militia general)

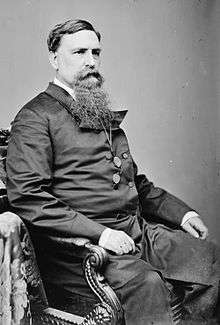

George Hume Steuart (1790–1867) was a United States general who fought during the War of 1812, and later joined the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. His military career began in 1814 when, as a captain, he raised a company of Maryland volunteers, leading them at both the Battle of Bladensberg and the Battle of North Point, where he was wounded. After the war he rose to become major general and commander-in-chief of the First Light Division, Maryland Militia.

George Hume Steuart | |

|---|---|

Major General George H. Steuart reviews the Maryland Militia at Camp Frederick, 1843 | |

| Born | November 1, 1790 Anne Arundel County, Maryland |

| Died | October 21, 1867 (aged 76) Baltimore, Maryland |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1814-1861 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 5th Maryland Regiment, Maryland Militia |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812

|

| Relations | George H. Steuart (grandfather) George H. Steuart (son) William Steuart (uncle) Richard Sprigg Steuart (brother) |

| Other work | planter, politician, lawyer |

During John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Steuart personally led a detachment of militia, and, as the prospect of civil war drew closer, he was among those who lobbied unsuccessfully for Maryland to secede from the Union. In 1861, at the start of the Civil War, Steuart left his home state of Maryland and joined the Confederacy, though at 71 years of age he was by then considered too old for active service. This did not prevent him from personally riding with Lee's army and even being captured at the First Battle of Manassas.

He is sometimes confused with his eldest son, Brigadier General George H. Steuart, who fought for the Confederacy at a number of major battles, eventually surrendering with General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox in 1865. Steuart died in 1867, his health and fortune ruined by his devotion to the Southern "lost cause".

Early life

Steuart was born in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, on November 1, 1790, the eldest son of Dr James Steuart of Annapolis [1](1755–1846), and Rebecca Sprigg, who were married on November 4, 1788.[2] James Steuart was a physician who served in the Revolutionary War, and was the son of George Hume Steuart (1700–1784), a Loyalist politician and tobacco planter who was colonel of the Maryland horse militia under Governor Horatio Sharpe.[3]

The young Steuart grew up partly at Sparrow's Point, his family's plantation in the Chesapeake Bay, and partly at their residence in West Baltimore, a substantial estate known as Maryland Square. Later he studied at and graduated from Princeton University.[4] Steuart also had a younger brother, Richard Sprigg Steuart, who grew up to become a physician and was an early pioneer of the treatment of mental illness.[5]

War of 1812 - Bladensburg and North Point

When war broke out between the United States and Great Britain, Steuart (then Captain Steuart) raised a company of Maryland volunteers, known as the Washington Blues,[6] part of the 5th Maryland Regiment[7] commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Sterett.[8] They saw action at the Battle of Bladensburg (August 24, 1814),[9] where the Americans, including the 5th Regiment, were routed by the British. Although the 5th had "evinced a disposition to make a gallant resistance", it was flanked by the redcoats and forced to retreat in some disorder.[10] After the battle, British forces entered Washington, D.C., and set fire to a number of buildings in the city.

Steuart's regiment fought better at the Battle of North Point (September 12, 1814),[1] where the militia were able to hold the line for an hour or so before making a fighting retreat during which Steuart was wounded.[11][12] Some of the militia regiments, such as the 51st, and some members of 39th, broke and ran under fire, but the 5th and 27th held their ground and were able to retreat in reasonably good order having inflicted significant casualties on the advancing enemy.[13] Corporal John McHenry of the 5th Regiment wrote an account of the battle:

- "Our Regiment, the 5th, carried off the praise from the other regiments engaged, so did the company to which I have the honor to belong cover itself with glory. When compared to the [other] Regiments we were the last that left the ground...had our Regiment not retreated at the time it did we should have been cut off in two minutes." [13]

Although North Point was a tactical defeat for the Americans, it would prove a turning point in the War of 1812. The British took significant losses, including their commanding officer Major General Robert Ross, and, lacking the strength to take the city of Baltimore, they eventually withdrew.

Post-war career

Steuart was soon promoted to lieutenant-colonel of the 5th Regiment,[14] and after the war he trained as a lawyer, being listed in the Baltimore City Directory of 1816 as Attorney-at-Law.[1] He was a member of the Maryland House of Delegates for Baltimore in 1827 and 1828, serving two one-year terms,[15] and in 1835 he stood unsuccessfully for election to Maryland's 4th congressional district, running as an independent candidate.[16] In around 1827 or 1828 his portrait was painted by the Baltimore portrait painter Philip Tilyard.[17]

First Light Division formed

In 1833 a number of Baltimore regiments were formed into a brigade, and Steuart was promoted from colonel to brigadier general.[19] From 1841 to 1861 he was Commander of the First Light Division, Maryland Volunteer Militia.[20][21] Until the Civil War he would be the Commander-in-Chief of the Maryland Volunteers.[22][23] The First Light Division comprised two brigades: the 1st Light Brigade and the 2nd Brigade. The First Brigade consisted of the 1st Cavalry, 1st Artillery, and 5th Infantry regiments. The 2nd Brigade was composed of the 1st Rifle Regiment and the 53rd Infantry Regiment, and the Battalion of Baltimore City Guards.[18]

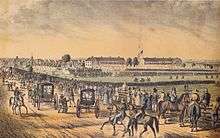

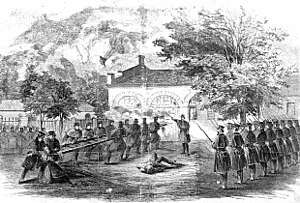

In 1843 Steuart reviewed his troops and those of a visiting regiment from Pennsylvania at Camp Frederick, accompanied by Governor David R. Porter of Pennsylvania and various senior officers. The event was attended by "an immense concourse of spectators",[23] and was commemorated in a lithograph published in the same year.

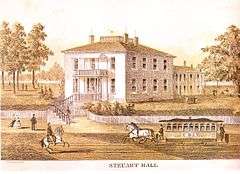

On July 19, 1844, the Boston City Greys visited Baltimore, and marched in parade with various companies of the 53rd Regiment. Steuart hosted a party for the visiting militia, which was held at his family estate in West Baltimore, known as Maryland Square. The event was celebrated by extensive coverage in the Baltimore American and, like the previous year's visit from Pennsylvania, was commemorated in a lithograph.[24]

Steuart also appears to have formed an acquaintance with the social reformer Dorothea Dix, who in July 1850 was his guest at Steuart's country residence Sparrow's Point on the Chesapeake Bay. Also a guest was the Swedish feminist and activist Fredrika Bremer, who wrote in a letter to her sister Agathe: "Late in the evening I sat in the most beautiful moonlight with Miss Dix on the veranda of General Stuarts' [sic] house, looking towards the shining river and the wide Chesapeake Bay, listening to the story of her simple yet remarkable life".[25] Dix was a campaigner for better treatment of the mentally ill, a subject which was also the life's work of Steuart's brother, the physician Richard Sprigg Steuart. Also among Steuart's social circle was the writer Washington Irving, who was a regular guest at Maryland Square.[26]

Know-Nothing elections

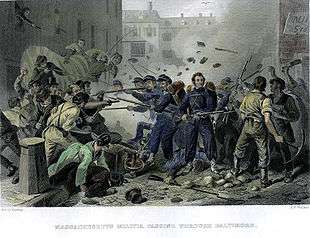

During the mid-1850s public order in Baltimore was threatened by the election of candidates of the Know Nothing party.[27] In October 1856 the Know Nothing Mayor Samuel Hinks was pressed by Baltimorians to order Steuart's militia in readiness to maintain order during the mayoral elections, as violence was anticipated. Hinks duly gave Steuart the order, writing that he should "hold yourself with your command, or such portion thereof as you may deem necessary, in readiness to march at a moment's warning, fully armed and equipped for active service".[28] In response, Steuart ordered his men to "assemble in marching order" on November 4 and await further orders.[28] However, perhaps fearful of greater violence, the mayor soon rescinded his order.[29] On October 31 he met with Steuart and requested that the general make his soldiers ready, but not assembled, and Steuart duly countermanded his original order.[28] On polling day violence soon broke out, with shots exchanged by competing mobs.[29] In the 2nd and 8th wards several citizens were killed, and many wounded.[30] In the 6th ward artillery was used, and a pitched battle fought on Orleans St between Know Nothings and rival Democrats, raging for several hours.[30] The result of the election, in which voter fraud was widespread, was a victory for the Know Nothings by around 9,000 votes.[30]

In 1857, fearing similar violence at the upcoming elections, Governor Thomas W. Ligon ordered Steuart to hold the First Light Division, Maryland Volunteers in readiness.[31] Ligon carried a "painful sense of duty unfulfilled" owing to the violence of the previous year, and was determined to maintain order.[32] However, Mayor Thomas Swann successfully argued for a compromise measure involving special police forces to prevent disorder, and Ligon once again balked at the use of military force. He did not formally rescind the order to Steuart's militia, but rather proclaimed that he did not "contemplate the use, upon that day of the military force which I have ordered to be enrolled and organized." [31][32] This time, although there was somewhat less violence than in 1856, the results of the vote were again compromised by the use of force and intimidation. Mayor Swann was duly re-elected, albeit in a heavily disputed ballot.[31]

Slavery and the coming of the Civil War

Steuart's family were slaveholders and strong supporters of the South's "peculiar institution", although they supported the gradual abolition of slavery by voluntary means. In 1828 Steuart served on the board of managers of the Maryland State Colonization Society, of which Charles Carroll of Carrollton, one of the co-signers of the Declaration of Independence, was president. Steuart's father, James Steuart, was vice-president, and his brother Richard Sprigg Steuart was also on the board of managers.[33] The MSCS was a branch of the American Colonization Society, an organization dedicated to returning black Americans to lead free lives in African states such as Liberia. The society proposed from the outset "to be a remedy for slavery", and declared in 1833:

- "Resolved, That this society believe, and act upon the belief, that colonization tends to promote emancipation, by affording the emancipated slave a home where he can be happier than in this country, and so inducing masters to manumit who would not do so unconditionally...[so that] at a time not remote, slavery would cease in the state by the full consent of those interested."[34]

In around 1842 Steuart inherited from his uncle William Steuart (1754–1838) "2,000 acres, in several tracts of land, the best of which was Mount Steuart; and 125 slaves", becoming himself a substantial landowner and slaveholder.[35] In 1846 his father James Steuart died, and he inherited Maryland Square, his family's mansion in the western suburbs of Baltimore.[36]

John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry

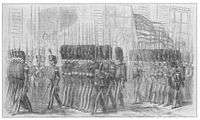

In 1859 Steuart's militia participated in the suppression of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, an abortive attempt to ignite a slave rebellion.[22] Steuart personally led six companies of Militia: the City Guard, Law Greys and Shields Guard from Baltimore, and the United Guards, Junior Defenders and Independent Riflemen from the city of Frederick.[18] The departing Baltimore militia were cheered on by substantial crowds of citizens and well-wishers.[37] After Harper's Ferry, militias in the South began to grow in importance as Southerners began to fear slave rebellion inspired by Northern Abolitionists.[38]

The following year, in a letter to the National Intelligencer on November 19, 1860, Steuart congratulated the editors on their support for the Fugitive Slave Acts, and set out his own support for the Supreme Court's 1857 decision to uphold slavery in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford. He also criticized the recent election of then President-elect Abraham Lincoln on a platform opposed to slavery. Steuart argued for "the invalidity of Lincoln's election, because of the negro votes cast and counted for him in the states of New York, Ohio, and Massachusetts".[39]

In 1861, as war grew closer, Steuart established a family trust, administered by four of his sons, in order to look after his large family. The trust income consisted chiefly of ground rents from his estates.[40]

Civil War

By April 1861 it had become clear that war was inevitable. On April 16 Steuart's eldest son, George H. Steuart, then an officer in the United States Army, resigned his captain's commission to join the Confederacy.[41] On April 19 Baltimore was disrupted by riots, during which Southern sympathizers attacked Union troops passing through the city by rail, causing what were arguably the first casualties of the Civil War. Steuart ordered his militia to assemble, armed and uniformed, to repel the Federal soldiers,[22] as Steuart himself was strongly sympathetic to the Confederacy, along with most of his senior officers. It is possible that he may even have contemplated an invasion of Washington DC.[42] Perhaps knowing this, and no doubt aware that public opinion in Baltimore was divided, Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks refused to order out the militia.[43] Steuart's eldest son commanded one of the city militias during the disturbances of April 1861 and, in a letter to his father, the younger Steuart wrote:

- "I found nothing but disgust in my observations along the route and in the place I came to – a large majority of the population are insane on the one idea of loyalty to the Union and the legislature is so diminished and unreliable that I rejoiced to hear that they intended to adjourn...it seems that we are doomed to be trodden on by these troops who have taken military possession of our State, and seem determined to commit all the outrages of an invading army." [44]

Steuart's brother, the physician Richard Sprigg Steuart, was also in Baltimore during the riots and he held a somewhat different view of the state of public opinion in the city:

- "I happened to be in Baltimore on the night of the 19th April 1861, and witnessed the outburst of feeling on the part of the people. Generally, when the Massachusetts troops were passing thru the city of Baltimore, it was evident to me that 75 p.c. of the population was in favour of repelling these troops. Instinctively the people seemed to look upon them as intruders, or as invaders of the South, not as defenders of the City of Baltimore. How or by whom the first blow was given can not be now ascertained, but the feeling of resistance was contagious and powerful. The Mayor of the City, nevertheless, though it his duty to keep the peace and protect these troops in their passage thru Baltimore." [45]

Steuart and his son made strenuous efforts to persuade Marylanders to secede from the Union, and to use the militia to prevent the occupation of the State by Union soldiers. But by April 25 his efforts had become largely defensive. In a letter of the same date he wrote to Governor of Virginia John Letcher stating that he was:

- "very anxious to hold a strong position at or near the Relay House so as to guard and keep open [railway communications] and at the same time cutting it off from Washington"[46]

Steuart's efforts to persuade Maryland to secede from the Union were in vain. On April 29, the Maryland Legislature voted 53–13 against secession. and the state was swiftly occupied by Union soldiers to prevent any reconsideration.

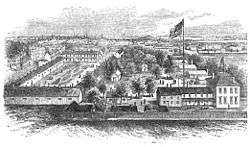

Flight to Virginia

The political situation remained uncertain until May 13, 1861 when Union troops occupied the state, restoring order and preventing any further move to secession, and by late summer Maryland was firmly in the hands of Union soldiers. Arrests of Confederate sympathizers soon followed, and General Steuart fled to Charlottesville, Virginia, after which much of his family's property was confiscated by the Federal Government.[47] Maryland Square was seized by the Union Army and re-named Camp Andrew after Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew, a noted abolitionist.[48] Union troops were quartered in Steuart's mansion and Jarvis Hospital was soon erected on the grounds of the estate, to care for Federal wounded.[49]

Steuart was not alone in fleeing to Virginia to join the Confederacy. Many members of the newly formed Maryland Line in the Confederate army would be drawn from Steuart's Maryland militia,[50] though at age 71 Steuart was personally judged too old for active service. Despite this, he spent much of the war following the Confederate army and was present at or near a number of battles,[51] including Gettysburg,[52] and the First Battle of Manassas, where he was so close to the fighting that he was actually captured by Union forces. Fortunately, when it was discovered he was not a serving officer in the Confederate army he was soon released.[53]

The cost of war

Steuart is often confused with his eldest son, Brigadier General George H. Steuart,[54] who rose rapidly in the Confederate command, distinguishing himself at the First Battle of Manassas and fighting for the South at many battles including Cross Keys, Winchester and Gettysburg. Wounded, captured and exchanged, the younger Steuart would eventually surrender with General Lee at Appomattox. Local residents in Baltimore would come to know father and son as "The Old General" and "The Young General".[55]

Steuart's third son, Lieutenant William James Steuart (1832–1864), also fought for the Confederacy. During the Battle of the Wilderness he was severely wounded in the hip, and was sent to Guinea station, a hospital for officers in Richmond, Virginia. There, on 21 May 1864, he died.[56] A friend of general Steuart at the University of Virginia wrote to his bereaved father:

- "You will not charge me, I trust, with intruding on the sacredness of your grief, if I cannot help giving expression to my deep, heartfelt sympathy with your great sorrow. You have sacrificed so much for the righteous cause already, that I know you will present this last and most precious offering also with the fortitude of your character and the submission of a Christian. Still, I know how valuable this son of yours had been to your interests, how dear to your heart, and I cannot tell you, with what deep and sincere grief I heard of your terrible loss." [57]

Steuart's brother, the physician Richard Sprigg Steuart, chose not to leave Maryland, remaining in his home state throughout the war, though his open support for the Confederacy meant that he too became a fugitive from the federal authorities. Baltimore resident W W Glenn described him as living in constant fear of capture:

- "I was spending the evening out when a footstep approached my chair from behind and a hand was laid upon me. I turned and saw Dr. R. S. Steuart. He has been concealed for more than six months. His neighbors are so bitter against him that he dare not go home, and he committed himself so decidedly on the 19th April and is known to be so decided a Southerner, that it more than likely he would be thrown into a Fort. He goes about from place to place, sometimes staying in one county, sometimes in another and then passing a few days in the city. He never shows in the day time & is cautious who sees him at any time. He has several negroes in his confidence at different places." [58]

General Steuart corresponded regularly with a friend, Sally J. Newman, in Hilton, Va. during course of the war. In these letters, which are held by the Maryland Historical Society, Steuart deplores Negro suffrage and the general condition of the country.[40]

After the war

Steuart's dedication to the "Lost Cause" of the Confederacy would prove a disaster for him and his family. Although Maryland Square was restored to him after the war, neither he nor his children would live there again.[59] Jarvis hospital was closed in 1865, at the war's end, and in the summer of 1866 the buildings were auctioned off, permitting successful bidders 10 days from the date of auction in which to remove their purchases from the grounds.[60]

After the war Steuart travelled to Europe, but returned to Maryland in 1867,[51] where he died on October 21, 1867, age 77. He is buried at Greenmount Cemetery, Maryland, along with his wife, eldest son and other members of his family.[61]

Family life

Steuart married Ann-Jane Edmondson in Baltimore on May 3, 1836. They had 10 children:

- George H. Steuart (1828–1903), Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War.

- Isaac Edmondson Steuart (1830–1891). Suffered from mental illness and was "in and out of mental institutions" for much of his life.[40]

- Lieutenant William James Steuart (1832–1864), C.S.A. Killed at the Battle of the Wilderness, 1864.[56]

- Thomas Edmondson Steuart (1834–1866)

- Dr James Henry Steuart (1835–1892)

- Mary Elizabeth Steuart (1837–1840)

- Ann Rebecca Steuart (1839–1865)

- Charles David Steuart (1841–1921). Like his older brother Isaac, suffered from mental illness and was "in and out of mental institutions" for much of his life.[40]

- Margaret Sophia Steuart (1843–1860)

- Henrietta Elizabeth Steuart (1846–1867)[62]

Legacy

Perhaps not surprisingly, as Maryland had remained loyal to the Union, there is no monument to Steuart in his home state. Maryland Square was demolished in 1884, and little trace of his mansion, or Jarvis Hospital, remains today. However, in 1919 the Sisters of Bon Secours themselves opened a hospital, their first in the United States, at 2000 West Baltimore Street, very near the location of the former Jarvis Hospital.[63] The Grace Medical Center continues to flourish today, and forms an important part of the modern neighbourhood, which still retains the name of Steuart Hill.[59][64]

Notes

- The Huntington Library quarterly. 1949.

- Brumbaugh, Gaius Marcus, p.473, Maryland Records: Colonial, Revolutionary, County, and Church Retrieved January 2012

- Nelker, p.66

- Harrison, Bruce, p.937 The Family Forest Descendants of Lady Joan Beaufort Retrieved August 28, 2010

- Richard Sprigg Steuart and the History of Spring Grove Hospital Archived 2010-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Register of the Military Order of Foreign Wars of the United States, National Commandery (1900) Retrieved Jan 14 2010

- Register of the Military Order of Foreign Wars of the United States, p.101, National Commandery (1900) Retrieved Jan 14 2010

- Hickman, Nathaniel, p.100, The citizen soldiers at North Point and Fort McHenry, September 12 & 13 1814, published by James Young,(1889) Retrieved Jan 14 2010

-

- Marine, William Matthew, p.326, The British Invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815 Retrieved Jan 14 2010

- Brackenridge, Henry Marie, p.249, History of the Late War between the United States and Great Britain, Philadelphia (1836). Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- Richardson, p.228

- American Quarterly Review, Issues 35-36, by Robert Walsh, p.495 (1835) Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- George, p.143

- Niles' Weekly Register, Volume 14, by Hezekiah Niles (1818) Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- Archives of Maryland House of Delegates, Baltimore (1790–1864) Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Extra Globe dated Wednesday October 7 1835 Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- www.tilyard.net Retrieved April 2013

- Field, Ron, et al., p.33, The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved May 10, 2010

- Griffith, Thomas W., p.257, Annals of Baltimore, 1833 Retrieved February 28, 2010

- Sullivan David M., The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War: The First Year, p.286, White Mane Publishing (1997). Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Sparks, Jared, and others, p.168, The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge, Volume 10 Retrieved August 29, 2010

- Hartzler, Daniel D., p.13, A Band of Brothers: Photographic Epilogue to Marylanders in the Confederacy Retrieved March 1, 2010

- Niles Weekly register, Volume 62, p.177 Retrieved March 2, 2010

- Rice, p.119

- Sjoberg, Leif, American Swedish (1973) Retrieved January 2012

- Richardson, p.226

- Andrews, p.475

- Melton, p.103

- Andrews, p.476

- Andrews, p.477

- Andrews, p.478

- Melton, p.159

- The African Repository, Volume 3, 1827, p.251, edited by Ralph Randolph Gurley Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- Stebbins, Giles B., Facts and Opinions Touching the Real Origin, Character, and Influence of the American Colonization Society: Views of Wilberforce, Clarkson, and Others, published by Jewitt, Proctor, and Worthington (1853). Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Nelker, p.131, Memoirs of Richard Sprigg Steuart.

- Nelker, p.107

- Andrews, p.497

- Ken Burns, The American Civil War

- Letter from George H. Steuart to the National Intelligencer dated November 19, 1860, unpublished.

- archive of the Maryland Historical Society Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Cullum, George Washington, p.226, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Retrieved Jan 16 2010

- Lockwood, p.279 Retrieved June 2012

- Brugger, Robert J., p.285, Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980, Johns Hopkins University Press (1996) Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- Mitchell, Charles W., p.102, Maryland Voices of the Civil War. Retrieved February 26, 2010

- Mitchell, Charles W., p.101, Maryland voices of the Civil War. Retrieved February 26, 2010

- Lockwood & Lockwood, p.210, The Siege of Washington: The Untold Story of the Twelve Days That Shook the Nation Retrieved June 2012

- Brugger, Robert J., p.280, Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980 Retrieved Feb 28 2010

- Mitchell, p.166

- Nelker, p.120

- Goldsborough, p.9

- Hanson, p.272

- The English Confederate - The Life Of A Civil War General, 1815-1889, by Collett Leventhorpe, p.110. Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Scharf, John Thomas, p.668, The Chronicles of Baltimore Retrieved February 28, 2010

- Sjoberg, Leif, p.69, American Swedish (1973) Retrieved February 2011

- Steuart, William Calvert, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past", Sunday Sun Magazine, February 10, 1963.

- Nelker, p.67

- Mitchell, p.339

- Mitchell, Charles W., p.285, Maryland Voices of the Civil War Retrieved February 26, 2010

- Rice, p.290

- Rice, p.256

- Greenmount Cemetery website Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Nelker, p.67-68

- History of Bon Secours Hospital, Baltimore Retrieved Feb 7 2010

- Steuart, William Calvert, Article in Sunday Sun Magazine, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past", Baltimore, February 10, 1963

References

- Andrews, Matthew Page, History of Maryland, Doubleday Doran & Co, New York City (1929).

- Brackenridge, Henry Marie, p.249, History of the Late War between the United States and Great Britain, Philadelphia (1836). Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- Field, Ron, et al., The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved March 4, 2010

- George, Christopher T Terror on the Chesapeake, The War of 1812 on the Bay, White Mane Books (2000).

- Goldsborough, W. W., The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1.

- Gurley, Ralph Randolph, Ed., p.251, The African Repository, Volume 3 (1827). Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- Hanson, George Adolphus, Old Kent: The Eastern Shore of Maryland: Notes Illustrative of the Most Ancient Records Of Kent County, Maryland Published by John P. Des Forges (1876), ASIN: B0013KKEXE. Retrieved on Jan 11 2011

- Harrison, Bruce, The Family Forest Descendants of Lady Joan Beaufort Retrieved August 28, 2010

- Hickey, Donald R., The War of 1812, a Forgotten Conflict, University of Illinois Press (October 1, 1990) ISBN 0-252-06059-8 Retrieved January 11, 2010

- Hickman, Nathaniel, p.100, The Citizen Soldiers at North Point and Fort McHenry, September 12 & 13 1814, published by James Young (1889). Retrieved Jan 14 2010

- Leventhorpe, Collett, p.110, The English Confederate - The Life Of A Civil War General, 1815-1889 McFarland & Company (2006) Retrieved Jan 11 2010

- Marine, William Matthew, The British Invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815 Nabu Press (2010) ISBN 1-176-49230-6 Retrieved Jan 14 2010

- Melton, Tracy Matthew, Hanging Henry Gambrill - The Violent Career of Baltimore's Plug Uglies, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore (2005) ISBN 0-938420-93-3

- Mitchell, C. W., Maryland Voices of the Civil War, Johns Hopkins University Press (2007)

- Nelker, Gladys P., The Clan Steuart, Genealogical Publishing (1970).

- Papenfuse, Edward C. et al., Archives of Maryland, Historical List, new series, Vol. 1. Annapolis, MD: Maryland State Archives (1990).

- Richardson. Hester Dorey, Side-Lights on Maryland History: With Sketches of Early Maryland Families, Tidewater Publishing, 1967. ASIN: B00146BDXW, ISBN 0-8063-0296-8, ISBN 978-0-8063-0296-6.

- Shirk, Ida M., p.160, Descendants of Richard & Elizabeth (Ewen) Talbott of Popular Knowle Retrieved January 2012

- Sjoberg, Leif, American Swedish (1973) Retrieved February 2011

- Sparks, Jared, and others, p.168, The American Almanac and Repository of Useful Knowledge, Volume 10 Retrieved August 29, 2010

- Steuart, George H., Letter to the National Intelligencer dated November 19, 1860, unpublished, Archive of the Maryland Historical Society.

- Steuart, James, Papers, Maryland Historical Society, unpublished.

- Steuart, William Calvert, Article in Sunday Sun Magazine, "The Steuart Hill Area's Colorful Past", Baltimore, February 10, 1963.

- Sullivan, David M., The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War: The First Year, White Mane Publishing, (1997) Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- White, Roger B, Article in The Maryland Gazette, "Steuart, Only Anne Arundel Rebel General", November 13, 1969.

External links

- Grave of Major General George H. Steuart at www.greenmountcemetery.com Retrieved on Jan 11 2010

- Archives of Maryland Historical List House of Delegates, Baltimore City (1790–1864) Retrieved on Jan 11 2010

- Letters of Major General George H. Steuart from the Archive of the Maryland Historical Society Retrieved on Jan 11 2010

- Account of the role of the Maryland Militia at the Battle of North Point, at National Guard website Retrieved on Jan 11 2010

- The Huntingdon Library Quarterly, Volume 12 (1949). Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- Register of the Military Order of Foreign Wars of the United States, National Commandery (1900) Retrieved Jan 14 2010

- Extra Globe dated Wednesday October 7 1835 Retrieved Jan 15 2010