George Copeland

George Copeland (April 3, 1882 – June 16, 1971)[1] was an American classical pianist known primarily for his relationship with the French composer Claude Debussy in the early 20th century and his interpretations of modern Spanish piano works.

Career

A native of Massachusetts, George A. Copeland Jr. began piano studies as a child with Calixa Lavallée, the composer of "O Canada" and an important early member of the Music Teachers National Association (MTNA).[2] Copeland later worked at the New England Conservatory with Liszt pupil Carl Baermann, then traveled to Europe for studies with Giuseppe Buonamici in Florence and Teresa Carreño in Berlin.[3] Copeland was also coached in Paris by the British pianist Harold Bauer, concentrating on works of Schumann.[4] Early in the 20th century, Copeland fell in love with the works of then-unfamiliar French composer Claude Debussy. On January 15, 1904, Copeland gave one of the earliest-known performance of Debussy's piano works in the United States, playing the Deux Arabesques at Steinert Hall in Boston.[5] Copeland was not the first to perform Debussy in the United States; that honor went to Helen Hopekirk, a Scottish pianist who programmed the Deux Arabesques in Boston in 1902.[6] From 1904 until his final recital in 1964, Copeland played at least one work of Debussy on each of his recitals.

In the early 1900s, John Singer Sargent, a fellow Bostonian, introduced Copeland to Spanish music.[7] Copeland became an Iberian specialist, performing works of Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, Manuel de Falla and others throughout the United States and Europe. In 1909, he introduced three of Albéniz's Iberia suite to the United States, playing "Triana," "Malaga" and "El Albaicin" in Boston.[8]

In 1911, he met Debussy in Paris and spent four months studying with the composer, discussing and playing all of Debussy's piano works. This was a turning point in Copeland's life; until his death 60 years later, Copeland would recall his time with Debussy with the greatest affection and reverence, both in print and in conversation with friends. In 1913, Copeland gave the following account of their discussions:[9]

"I have never heard anyone play the piano in my life who understood the tone of every note as you do," remarked Debussy. "Come again tomorrow." This seemed praise indeed and I did go tomorrow. I found him much more genial than on my first visit, and then I went time after time, until finally I was with him about twice a week for three months. I bought new copies of his works, which he marked for me; I played his works and he criticised my work and showed me what to do and how to do it. In the end, he admitted that I played him just as he wanted to be played and represented to the people.

By 1955, Copeland had modified his account to have Debussy say: "I never dreamed that I would hear my music played like that in my lifetime.[10] In this later version, Copeland claimed that their meetings were daily, for four months, including periods of playing as well as long walks in the countryside.

Copeland gave many U.S. premieres of Debussy's works, as well as several world premieres. The most important was the world premiere of numbers X and XI of the Etudes on November 21, 1916, at Aeolian Hall in New York City.[11] The anonymous critic for Musical Courier was not particularly impressed with the Études, writing "These [études], in themselves, are not so absorbing as some of the composer's more familiar pieces, but as played by Mr. Copeland they acquired a delicate tone and glowing imagery that were surpassingly beautiful."[12] Other U.S. premieres of Debussy included the Berceuse héroïque and La Boîte à joujoux. The latter, played on March 24, 1914 at the Copley-Plaza Hotel in Boston, may have been the world premiere of the work.[13]

From 1918 through 1920, Copeland toured the United States with the Isadora Duncan Dancers, the "Isadorables"), a sextet of dancers who were the students and adopted children of dancer Isadora Duncan.[14] Sponsored by the Chickering Piano Company and managed by Loudon Charlton, Copeland and the dancers performed a shared program of dance and piano solos including works of Schubert, Chopin, MacDowell, Debussy, Grovlez, Albeniz, and others.[15] The reviews of Copeland were overwhelmingly positive, though many reviewers were less enthusiastic about the dancers[16] Annoyed at Copeland's success, the girls ordered Loudon Charlton to put Copeland in his place. The program covers were accordingly changed to read in large font "THE ISADORA DUNCAN DANCERS," with Copeland's name appearing in a smaller font beneath. Copeland saw this and refused to go onstage until all of the offending program covers in the audience had been removed.[17] In the spring of 1920, Copeland abruptly broke his contract for unknown reasons and went to Europe. Years later, Copeland told his student Ramon Sender that breaking his contract had fatal consequences for his career and that when he returned to the United States in the 1930s, no reputable manager would touch him.[18]

Living first in Italy, then on the island of Mallorca,where he lived in the village of Genova and had a good relationship with the neighbours becoming the godfather of Juana Maria Navarro, the daughter of one of his better friends. Copeland returned to the United States only periodically, giving Carnegie Hall recitals in 1925, 1928–1931 and 1933.[19] In 1930, he performed in Philadelphia and New York City with the Philadelphia Orchestra led by Leopold Stokowski, offering works of Debussy and De Falla. While living in Europe, he played at the Chopin Festival of Majorca, in Vienna with the Wiener Philharmoniker, at the Salzburg Festival, and in London. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Copeland returned to the United States.

Settling in New York City, he performed there annually at venues including Carnegie Hall, Town Hall and Hunter College, and made regular trips to Washington D.C. and Boston. In 1945, he toured with the soprano Maggie Teyte in an all-Debussy duo recital that included his arrangement of Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune.[20] Copeland played a Golden Jubilee Recital at Carnegie Hall on October 27, 1957, celebrating the 50th anniversary of his New York recital debut. The New York Times reviewer described his performance as "magical," calling Copeland's work "playing that stays in the memory."[21] In the spring of 1958, he suffered a fall at his vacation home in Stonington, Connecticut and broke his shoulder. He was unable to play for several years and believed his career to be over.[22] In 1963, he made a comeback, recording with famed engineer Peter Bartok and concertizing at schools and smaller halls on the East Coast. On May 11, 1964, Copeland performed his final recital at Sprague Memorial Hall, Yale University. Although he spoke in 1966 of a return to the concert stage, he never again performed in public.[23]

Copeland died of bone cancer in the Merwick Unit of Princeton Hospital in Princeton, New Jersey, on June 16, 1971. His cremated remains are held at the Ewing Cemetery in Ewing, New Jersey.[24]

Personal life

Copeland was open about being gay throughout his life. In 1913, he gave an interview to the Cleveland Leader in which he stated "I don’t care what people think of my morals. I never think anything about other people’s morals. Morals have nothing to do with me."[25] He indicated that Oscar Wilde was a favorite author.[26]

Throughout his life, the pianist delighted in exotic jewelry and scents, both considered effeminate in the early 20th century. He wrote in his unpublished memoirs:[27]

I have always had a passion for wearing jewelry, and whilst I know it is considered bad form, forbidding men to wear anything but a tiresome signet ring, I have taken the liberty of defying that convention all my life. Probably it grew out of my father's attitude. He was going to give me a watch on my birthday, and he asked me what kind I wanted. I wanted a wristwatch – they were still a rare novelty in those days. He said I could certainly have the wristwatch if I wanted it, but that I need never darken his door again. Men who wore jewels or wristwatches, or who used perfume, or anything that smelt agreeable, were considered effeminate. I felt if my masculinity or effeminacy were to be judged and decided by the bottle of scent, or the kind of jewel I wore, I had best give up! Jewels are another manifestation of beauty, and certainly perfume smells better than perspiration! I wear jewels because I love to look at them myself, and because I hope they give pleasure to others. They are not unrelated to music, for all music has color – the deep greens of forests, the limpidness of water, the passionate flash of rubies and diamonds.

Copeland's openness about his sexuality allegedly led to problems for composer Aaron Copland. In the 1930s, the pianist preceded the composer on a concert tour in South America. In one country George Copeland was apprehended on a "morals charge" and told never to return. When Aaron Copland arrived for his concerts, the authorities treated him frostily before he explained that he was Copland the composer, not Copeland the pianist.[28]

Around 1936, Copeland met a young German, Horst Frolich, at a restaurant in Barcelona, and they began a relationship that lasted for over thirty years. Frolich returned to the United States with Copeland that year, listing his occupation on the ship manifest as "secretary."[29] According to friends of the pianist, Copeland was adamant about Frolich's position as his partner; if you wanted the socially-desirable pianist to attend your party, Frolich had to be invited.[30] A December, 1942 New York Times social item reporting the guest list of a high-society gathering at the St. Regis in New York included Copeland, the violinist Fritz Kreisler and Frolich. Frolich committed suicide in 1972 after a dispute involving a property he was to inherit from a different lover.[31]

Programming

Although his repertoire contained several larger Romantic works, Copeland was alternately acclaimed and reviled as a miniaturist. He devised his programs according to his personal tastes. He said in a 1929 interview, "I don't want to convey any message. I play what I like the way I like it, and the audience generally likes it too. And I don't give a whoop about leaving the world a better place when I die."[32] In the early part of his career, he was viewed as an avant-gardist. By the time of his final recitals, he was patronized as a relic of times past.

A typical Copeland program included short works of a Baroque composer (Bach, Scarlatti, Grazioli, etc.), works of Chopin (generally a selection of mazurkas, waltzes and etudes), occasionally a larger work of Schumann or Beethoven, Debussy, and modern Spanish works by composers like Albeniz, Granados, Turina, DeFalla, Lecuona and others. He rarely deviated from this formula. He occasionally presented all-Debussy recitals, though more often such recitals included one or two non-Debussy works, such as Rameau or Couperin suites.

At the height of his career, Copeland often presented new works by contemporary composers, few of which stood the test of time. Some of the more esoteric composers featured in his programs: Nicholas Slonimsky, Victor de Sabata, Carl Engel, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Federico Longas, Ramon Zuera, etc. New works generally appeared for a season or two, before he dropped them from his repertoire. Copeland became less adventurous over time, programming with only a handful of less-familiar works, generally in the Spanish group.

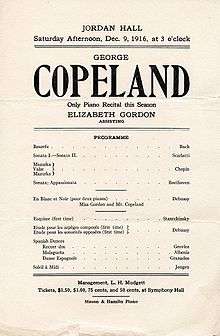

His Jordan Hall recital of December 1916, for example, included the Boston premières of several Debussy works, the Beethoven "Appassionata" Sonata op. 57, and a work by the obscure Belgian composer Joseph Jongen.

Critical reception

Critics respected Copeland as a gifted artist, though some criticized his formulaic programming and pointed out his willingness to ignore the composer's printed directions. They invariably noted the enthusiasm of the large audiences who attended his concerts in the first half of the century. Many pointed out his luminous tone – large and full-bodied – possibly his greatest asset as a pianist. When they first met, his teacher Teresa Carreño demanded to know the source of his sound:[33]

"Wonderful tone, wonderful tone – how do you get it?"

I hesitated. "Well, I don't know exactly how I get it, but I know what I want to hear." "That's utter nonsense!" she exclaimed. "it doesn't make any difference what you want to hear. I want to know how you put your finger on a given key and produce a given quality of sound."

"That is exactly what I do not ever wish to know." And we glared at each other.

Philip Hale in the Boston Herald (February 14, 1908)

Mr. Copeland has individuality; he has a marked style of his own. This was shown within due bounds in the ensemble, as in the performance of solo pieces. He has an unusually musical touch, clear, sensitive, varied in color. He has a fleetness that he should not abuse; he has strength that is not aggressive or jarring. More than all this, he has true poetic feeling and with it an instinct for differentiation in sentiment. Each one of the solo pieces as he played it was delightful, and his performance of Debussy's Prelude was masterly in all respects.

Philip Hale in the Boston Herald (January 8, 1915):

...Mr. Copeland among pianists is as Swinburne said of Coleridge among poets, lonely and incomparable. He belongs to no school; he is no one's disciple. Playing Debussy's music more poetically and fantastically than any pianist we have heard, he yet cannot be called a specialist, for he played last night the music of MacDowell in the epic manner; his performance of Scarlatti's Pastorale, beautiful in every way, had the right touch of archaism; his Schumann was Schumannesque, and his interpretation of Chopin's pieces would surely have won the approval of Vladimir de Pachmann.

No Author, Toledo Times (October 18, 1919):

So great was the throng that crowded to the Woman's Building last night to hear the Copeland piano recital that a conductor on the Cherry street car line was heard to remark: "Thought the McCormack concert was Thursday night."

And worthy to be ranked with the two previous musical events of the week, the brilliant opening concerts of the Civic Music League and the Teacher's Course, was the playing of George Copeland, pianist extraordinare.

The auditorium seating 1200 persons was crowded to capacity before the hour for opening and latecomers willingly stood leaning against the wall during more than an hour's program by this wizard of the keyboard.

Copeland's playing was new to Toledo and it took the audience, in which was represented practically every musician and music fan in the city, by storm. Invited to a complimentary concert by the J.W. Greene Co., although the fame of the artist had been heralded, few were prepared for the masterful interpretations of Copeland.

He seems in a class by himself in his mastery over the instrument. Totally unlike physically the traditional pianist of the long locks and temperamental make-up and producing a first impression of a prosperous business or professional man of the day, the moment the player struck the opening chords, with which he elects to begin each of his numbers by way of preliminary, the cognoscenti knew that an artist had come among them.

And not only musicians but everybody in the audience passed immediately under his spell. A piano recital, the most deadly form of entertainment in the hands of mediocrity, had become for the time a thing of life and joy and personal satisfaction to every listener.

It will be long before Toledo will hear a more perfect rendition of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata than that with which Copeland opened his program. There followed a Gavotte and Musette by Gluck, two sprightly French dances and then Chopin. It was the Chopin Waltz, Op. 70 no. 3 which was the first number to be repeated by the Ampico, a roll made from Copeland's playing being substituted for the fingers of the pianist.

As an interpreter of the impressionistic Debussy, Copeland betrayed his real greatness. Such limpid, liquid tones, in the Reflections in the Water; such sprightliness in Danse de Puck (Dance of Puck)! At the conclusion of the Debussy group, one number of which was repeated by the Ampico, after responding with bows four times to the insistent applause, the artist, taking the compliment for the composer rather than to himself, played as the single encore of the evening, Debussy's A Night in Granada.

The three Spanish compositions with which the program closed showed the versatility of the pianist and were delightful.

"R.R.G" in the Boston Herald (January 4, 1929):

In Spanish music, to go on, Mr. Copeland strikes a new note which other performers, both high and low, should heed. With the lethargic movement too many of them affect, he shows no patience. Slowly, indeed, his Spaniards may move, and sometimes languorously. But move they do, every minute they hold the stage, and sometimes passionately, All thanks to Mr. Copeland! More thanks to him, too, for showing the world how to plan a long-rising climax.

Elizabeth Y. Gilbert in Musical America (January 16, 1929):

It was not until the Spanish group that well-known Boston critics, who consider it bad form to stay beyond a given point in the program, put back their hats and coats, compelled to stay by the phenomenon of George Copeland. Two Danses Espagnole, of de Falla and Granados, two pieces by Infante, made Mr. Copeland's large audience all but stamp their feet in rhythmic accompaniment.

To a deaf onlooker, it would seem that Mr. Copeland was banging at his piano unmercifully, and so he was, but with such powerful and vibrating tones, with such subtly hesitated syncopation, as in de Falla's Danse, that not only did the audience applaud wildly, not only did the above-mentioned critics remain, but Mr. Copeland was forced to give five or six encores, and even then could not satisfy the clamor for more. Mr. Copeland is wise to specialize in rarities; in these he is unique.

"C." in Musical America (March 10, 1938):

Mr. Copeland can always be relied upon to fashion a program with many features of piquant interest and he did not fail his large public with the list he offered on his return to the local concert stage after an absence of several seasons....The pianist's playing of the Griffes and Debussy group did not maintain so consistently high a level, but with his unforgettable projection of 'Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut' he reached the climax of his evening's achievements. In its subtle and suggestive evocation of an enthralling mood this was truly creative playing of an order rarely experienced. He also brought imaginative atmosphere and much beauty and variety of tonal color to 'L'apres-midi d'un faune', but his interpretation of the added 'Clair de lune' was disappointing in its lack of poetic mood. Too rapid a tempo was adopted for a full realization of the grace and beauty of Griffes' 'The White Peacock.'.... The audience's enthusiasm was aroused to a high pitch at many points.

Olin Downes in the New York Times (November 1, 1938):

George Copeland, a pianist of unique accomplishments, who is completely unique in his style, and lonely in certain interpretive qualities, had a remarkable success when he appeared in recital last night at Carnegie Hall. A large audience, attentive and appreciative from the beginning, became so enthusiastic as the program proceeded that at last it was cheering the pianist, who played encores for half an hour before the lights were lowered in the hall....He has a tone of the most exceptional roundness and beauty. He has an instinct for color and nuance which cannot be taught or communicated. He understands the music that he plays much more by intuition than by reasoning it out – and perhaps this is the only way in which music can be thoroughly understood.

J.D.B. in the New York Herald-Tribune (December 12, 1942):

There was an informal charm about Mr. Copeland's performances of the Geminiani and Haydn Sonatas and the Chopin Waltz and Etude. He played as though he were playing for a group of intimate friends, and not for a Town Hall audience. His unceremonious approach served him less well with the Schumann "Etudes Symphoniques," which will not stand for anything less than the most professional treatment. Here his technical shortcomings were too prominent to permit even a passably accurate account of the music.

As heretofore, Mr. Copeland's most impressive interpretations were those of the modern works on his list. In all of these he was in his element, investing them with fascinating tonal tints and hues and the essential touch of fantasy.

Arthur Berger in the New York Herald-Tribune (February 19, 1950):

Mr. Copeland's Debussy is as natural as if it were being improvised on the spot, and Debussy, for all its clarity of form should have some of the character of improvisation. It should also seem often to come from far away, transmitted as if through a gauze, with the caressing touch Mr. Copeland has completely mastered. We do not hear "Les terrasse des audiences" or "Feuilles Mortes" presented these days with such exquisite balancing of sonorities.

I do not share the conviction of his many ardent devotees, well represented yesterday, that he is the only one that plays Debussy well, or that everything he does with it is perfection itself. Without being letter perfect he can, of course, convey the shape of a piece astonishingly. For my part, however, I was troubled by some details I could not hear yesterday, and by the blurring in some, but not all, of the rapid passages. "Feux d'artifice" has many quiet measures, but through technical difficulties, I suspect, he made it stormy almost throughout, and approached the gently rippling passages like tone clusters. I am not sure the relaxed quality is appropriate at all times, for it gives some passages a certain limpness.

J.B. in the New York Times (February 22, 1956):

It is always interesting to hear a performer who, like Mr. Copeland, was a friend of Debussy and other Parisian composers in the early days of this century. Mr. Copeland belongs to the school of Debussy-players who use the pedal generously, and play with such rhythmic freedom that two successive measures are not often in the same tempi.

Although the word "brilliant" does not come to mind when one hears Mr. Copeland's playing, it has a casual, informal quality that is very charming.

Recordings

From 1933 to 1940, Copeland recorded a large portion of his repertoire for RCA Victor. The most-represented composer was Debussy, including excerpts from the Preludes, Images, Estampes, Children's Corner and Suite Bergamasque, as well as many Spanish piano works including those of Albeniz, Granados and de Falla, and more obscure composers like Gustavo Pittaluga, Joaquin Turina, Raoul Laparra, Federico Longas. These performances are explosive, displaying Copeland's command of rhythm and his unique ability to ascend to the climax of any work in a blaze of pianistic color. Copeland's RCA Victor recordings are available on a two-CD Pearl set, "George Copeland – Victor Solo Recordings" (PRL 0001).

In 1937, Copeland recorded a number of songs with well-known Spanish soprano Lucrezia Bori, including works of DeFalla, Nin and Obradors. In the early 1950s, he recorded two discs for MGM Records (all-Debussy and all-Spanish), and in the early 1960s he made private recordings engineered by Peter Bartok and distributed by his agent, Constance Wardle.[34]

Repertoire

Isaac Albeniz: El Albaicin, El Polo, Malaga, Triana (Iberia); Malaguena ("Rumores de la Caleta"); Seguidillas; Tango in D; Zortzico

J. S. Bach: Chromatic Fantasie; English Suite no. 5; Italian Concerto

Ludwig v. Beethoven: Sonata in c#, op. 27/1 ("Moonlight"); Sonata in f, op. 57 ("Appassionata")

Joaquin Cassado: Hispania, for piano and orchestra (U.S. Premiere, Detroit, 1919)

Emmanuel Chabrier: Bourrée fantasque; España (arr. Copeland); Habañera

Frederic Chopin: Ballades no. 1 & 3; Etudes (selections); Mazurkas (selections); Waltzes (selections)

Claude Debussy: Berceuse héroïque (U.S. premiere, 1915); La Boîte à joujoux (U.S., possible world premiere, March 23, 1914); En blanc et noir; Estampes; Etudes X & XI (world premiere, 1916); Images I & II; L'isle joyeuse; Pour le piano; Preludes Livre I & II (excerpts)

Manuel de Falla: Transcriptions from El Amor Brujo, La vida breve; Nights in the Gardens of Spain

Gabriel Grovlez: Evocacion; Recuerdos; Reverie

Franz Liszt: Paganini Etudes II, III, V; Un Sospiro; Spanish Rhapsody; Venezia a Napoli

Maurice Ravel: Alborada del gracioso (Miroirs); Rigaudon (La Tombeau de Couperin); Sonatine

Robert Schumann: Faschingschwank aus Wien, op. 26; Symphonic Etudes, op. 13

Turina: A los Toros, Los bebedores de manzanilla; Fandango; Romantic Sonata; Sacro-Monte

References

- David Dubal, The Art of the Piano (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 2005), 78.

- Untitled manuscript, George Copeland Papers (1910–1967), Box 2/17, NYPL

- George Copeland, Unpublished manuscript, "Music, My Life." George Copeland Papers, 1910–1967. NYPL, New York.

- Peter Knapp, "George Copeland is Impressive in Stonington Theatre Recital." The Day (New London, CT: July 17, 1954).

- Charles Timbrell. "Performances of Debussy's Piano Music in the United States (1904–1918). Debussy Cahiers no. 21 (Paris, France: 1997), 63.

- Orchestra, Boston Symphony (1910). "Programme".

- Frederic Bradlee. "George Copeland, Inimitable and Alone." George Copeland Papers, 1910–1967. NYPL, New York.

- "Musical Events in Boston." Christian Science Monitor. November 3, 1909: 10.

- Archie Bell. "Copeland and Debussy," The Cleveland Plain-Dealer, January 15, 1913.

- George Copeland. "Debussy, the Man I Knew" The Atlantic Monthly (January, 1955), 34–38.

- James R. Briscoe, Debussy in Performance (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 113.

- Anonymous, Musical Courier, December 14, 1916.

- Anonymous. "Copley Plaza: Mr. Copeland," Boston Transcript, March 25, 1914.

- Merle Armitage, Accent on America (NY: E. Weyhe, 1944), 185.

- Program examples can be found at the NYPL Website

- F.D., "Sunday’s Sounds in the Music Halls," Chicago Daily Tribune. May 5, 1919: 23.

- Armitage, Accent on America, 185.

- Ramon Sender, "George Copeland," E-mail to the author. June 25, 2009.

- Carnegie Hall Archives, George Copeland Performance List, received via email, 2/3/2010.

- Recital Program, "Debussy Gala," (Academy of Music, Philadelphia, PA: October 23, 1945), author's collection.

- E.D. "Copeland Heard in Piano Recital." New York Times. October 28, 1957: 30.

- "Pianist Sues for $100,000." Charleston Gazette. January 26, 1959: 10.

- Mary Watkins Cushing. "Impressionist: Pianist George Copeland recalls his lifetime in music." Opera News (November, 1966), 7.

- Death Certificate for George Copeland, June 16, 1971, State File No. 31141, New Jersey Department of Health. Photocopy in possession of author.

- Raymond N. O'Neil. "Many-Ringed Virtuoso Hates Popularity and Fat." Cleveland Leader, January 16, 1913.

- In the early 20th century, Oscar Wilde's name was synonymous with homosexuality. In E.M. Forster's 1914 novel Maurice, the title character admits his sexuality to a doctor by revealing himself to be "an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort."

- Untitled manuscript, p. 130-131. George Copeland Papers (1910–1967), Box 2/17, NYPL

- Paul Moor. "How Aaron Copland came by that odd surname." Posted December 1, 2007, accessed July 12, 2010. Archived September 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- S.S. Britannic ship manifest, List 10: October 2, 1936.

- Sister Benedicta Sender, Phone Interview with the author, August 11, 2009.

- Connecticut State Police Report, Case # E-72-3453-C, December 4, 1972.

- Quoted in "Alias George Copeland" Musical America (January 19, 1929), page unknown.

- Untitled manuscript, p. 9. George Copeland Papers (1910–1967), Box 2/17, NYPL

- For the complete George Copeland discography and a brief discussion of his recordings and career, see Jerrold Moore's article in Recorded Sound (January, 1967), p. 142–147.

External links

- George Copeland plays Debussy's L'après-midi d'un faune on YouTube

- George Copeland plays Debussy's La Cathédrale Engloutie on YouTube

- George Copeland: The Victor Solo Recordings (Amazon.com)

- George Copeland: The Private Recordings, 1957–1963 (Amazon.com)

- Copeland's complete rollography, a listing of all the piano rolls made for the Ampico Co.

- A collection of Isadorables programs featuring Copeland (NYPL.org)