Geography of Kaziranga National Park

Kaziranga National Park (Assamese: কাজিৰঙা ৰাষ্ট্ৰীয় উদ্যান, Kazirônga Rastriyô Uddyan, IPA: [kaziɹɔŋa ɹastɹijɔ udːjan] (![]()

Kaziranga is a vast stretch of tall elephant grass, marshland and dense tropical moist broadleaf forests crisscrossed by four main rivers — Brahmaputra, Diphlu, Mora Diphlu and Mora Dhansiri and has numerous small water bodies. Kaziranga has been the theme of several books, documentaries and songs. The park celebrated its centenary in 2005 since its establishment in 1905 as a reserve forest.

Geography

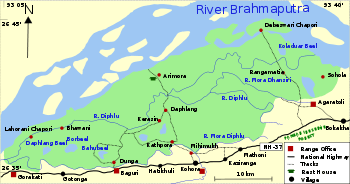

The park is located between latitude 26°30 N to 26°45 N and longitude 93°08 E to 93°36 E in the Kaliabor subdivision of the Nagaon district and the Bokakhat subdivision of the Golaghat district, in the state of Assam in India.[1] It is roughly 40 kilometres (25 mi) long and 13 kilometres (8 mi) wide, with an area of 378.22 km², having lost around 51.14 km² to erosion by the Brahmaputra.[2] A total addition of 429 km2 (166 sq mi) along the present boundary of the park has been made and notified with separate national park status to provide extended habitat for increasing population of wildlife or as a corridor for safe movement of animals to Karbi Anglong Hills.[1] :p.06

The southern border of the park is roughly defined by the Mora Diphlu river. Further south are the hills of Barail and the Mikir. The National Highway NH-37 was once the formal southern boundary of the park.[1] The Brahmaputra River constitutes the dynamically changing Northern boundary of the park. The other rivers in Kaziranga are Diphlu, Mora Diphlu and Mora Dhansiri.[3] Kaziranga is mostly flat expanses of fertile alluvial silt (part of the highly fertile Middle Brahmaputra alluvial flood plains),[1] exposed sandbars, riverine flood-formed lakes called Beels (Beels make up as much as 5% of the surface area)[1] and elevated flats called chapories where animals shelter during floods. Many artificial chapories have been built with the help of the Indian Army.[4][5] The average altitude of the park ranges from 40 metres (131 ft) to 80 metres (262 ft),[1] with the Mikir Hills to the south of the park rising to around 1,220 metres (4,003 ft).[1]

Human habitation

There are no villages within the boundary of the park. However the area outside the boundary of the park is very densely populated. There were 39 villages within a 10 kilometres (6 mi) radius of the park, with an estimated population of 22,300 people in 1983–1984.[1] According to a 2002 report, the figure has risen by 184 villages with about 50,000 households.[3] A few new settlements have come up in recent times outside the park borders for servicing the booming eco-tourism industry.[3]

Geology

Per the plate tectonics, Assam is in the eastern most projection of the Indian Plate, where it is thrusting underneath the Eurasian Plate creating a subduction zone. It is postulated that due to the northeasterly movement of the Indian plate, the sediment layers of an ancient geocyncline called Tethys (in between Indian and Eurasian Plates) have been pushed upward to form the Himalayas mountain range.[6] Karbi Anglong plateau, which is situated to the south of the Kaziranga (along with the Khasi and Garo Hills) is originally part of the South Indian Plateau system. It is believed that due to the force exerted by the north-eastwardly movement of the Indian plate at the time of the Himalayan origin, a huge fault was created between the Rajmahal hills and the Karbi-Meghalaya plateau. Later, this depression was filled up by the depositional activity of numerous rivers. Today the Maghalaya and Karbi Anglong plateau remains detached from the main Peninsular block. Average height of this plateau varies from 300 metres (984 ft) to 400 metres (1,312 ft).[7]

Kaziranga National Park's landscape is the creation of natural forces of silt deposition and erosion that has been effected by the river Brahmaputra over hundreds of years. This ongoing process of erosion and deposition becomes more severe during the floods which occur at regular intervals during the monsoon season.[3] The Brahmaputra river in its 724 kilometres (450 mi) flow through Assam receives more than a hundred tributaries flowing down from the adjoining hills. Once the tributaries hit the river valley, they lose their momentum; deposit the silt they carry, form ox-bow lakes and alluvial fans and branch out before picking up their courses again to join the Brahmaputra.[8]

Biomes

Kaziranga is one of the largest tracts of protected land in the sub-Himalayan belt, and due to its high species diversity and presence of high-visibility species, has been described as a "biodiversity hotspot".[9]

The park is located in the Indomalayan realm, and the region falls in two ecoregions, the Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests of the Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome, and a frequently flooded variant of the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands of the Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome.

Notes

- "UN Kaziranga Factsheet". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- Lahan, P; Sonowal, R. (March 1972). "Kaziranga WildLife Sanctuary, Assam. A brief description and report on the census of large animals". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 70 (2): 245–277.

- Mathur, V.B.; Sinha, P.R.; Mishra, Manoj. "UNESCO EoH Project_South Asia Technical Report-Kaziranga National Park" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2006.

- Kaziranga National Park Archived 2006-05-01 at the Wayback Machine. WildPhotoToursIndia. Retrieved on 2007-02-27

- "State of Conservation of the World Heritage Properties in the Asia-Pacific Region –Kaziranga National Park" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 28 February 2007.

- Vasudevan, Hari; et al. (2006). "Distribution of Oceans and Continents". Fundamentals of Physical Geography. New Delhi: NCERT. p. 37. ISBN 81-7450-518-0.

- Vasudevan, Hari; et al. (2006). "Structure and Physiography". India:Physical Environment. New Delhi: NCERT. p. 17. ISBN 81-7450-538-5.

- "Physiography of Assam". Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Government of Assam. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2007.

- Phatarphekar, Pramila N. (14 February 2005). "Horn of Plenty". Outlook India. Retrieved 26 February 2007.