Genoese towers in Corsica

The Genoese towers in Corsica (French: Tours génoises de Corse, Corsican: Torri ghjenuvesi di a Corsica, singular : torre ghjenuvese di Corsica) are a series of coastal defences constructed by the Republic of Genoa between 1530 and 1620 to stem the attacks by Barbary pirates.

Corsica had been controlled by the Genoese since 1284 when they established their supremacy over the Pisans in the naval Battle of Meloria. Towards the end of the 15th century the Ottoman Turks expanded their control of the Mediterranean westwards and became a dominant maritime power in the region. In 1480 they sacked Otranto in southern Italy and in 1516 they took control of Algiers. In the first decades of the 16th century Turkish corsairs in galleys and fustas often rowed by Christian slaves began attacking villages around the Corsican coastline. Many hundreds of villagers were captured and taken away to be sold as slaves. The Genoese Republic responded by building a series of towers around the coastline. Most were built to a similar circular design with a roof terrace protected by machicolations. Nearly one hundred were constructed before the Genoese decided in around 1620 that they were unable to defend the island and abandoned the building program.

In 1794, during the French Revolutionary Wars, British naval forces struggled to capture a Genoese tower in Corsica near the Punta Mortella, one of two towers guarding the entrance to the port of Saint-Florent. Impressed by their effectiveness and simple design, the British built many similar towers calling them Martello towers.

The ruined Genoese towers are now a prominent feature of the Corsican coastline. Many have been listed as official Historical Monuments by the French Ministry of Culture.

History

Construction

The construction of these towers started in the 16th century, at the request of village communities to protect themselves against pirates. In 1531, the Genoese Bank of Saint George sent two extraordinary representatives, Paolo Battista Calvo and Francesco Doria, to inspect the fortifications defending the island from the Barbary corsairs.[1][2] In 1531, the construction of ninety towers on the Corsican littoral was decided, thirty-two of them in the Cap Corse.

The work began under the supervision of two new Genoese representatives, Sebastiano Doria and Pietro Filippo Grimaldi Podio. The objective was to extend to Corsica the system of vigilance already in force on the Mediterranean circumference. The towers performed three functions: they defended the villages and ports, they acted as landmarks for navigators and they allowed news of an attack to be rapidly signalled to other communities along the coast.[3]

An inventory of the coastal towers produced by the Genoese authorities in 1617 lists 86 towers.[4] Two additional towers were constructed before the building program was abandoned. These were the Torra di Sponsaglia (completed in 1619) and the Torra di Sant'Amanza (completed in 1620) both in the south of Corsica between Bonifacio and Porto-Vecchio. Of these 88 towers, little or nothing survives for twenty of them. Two towers on the list were already in a ruined state in 1617: the Torra di Vignale and the Torra di Travo, both on the east coast.[5]

Decline

The towers caused multiple problems for the Genoese authorities; their isolated locations made them prime targets for pirates and constructional defects caused collapses. Several inventories of the towers were carried out but no precise number could be determined. The Republic of Genoa also had to deal with many financial conflicts, quarrels of communities, defection of guards, unpaid debts, and requests for supplies or weapons.

Consequently, from the end of the 17th century until 1768, the date of the conquest of the island by France, the number of maintained towers decreased considerably. When Pasquale Paoli was elected President of the new independent Corsican Republic in 1755, only 22 towers remained, some of which were occupied by the French troops. The continual guerrilla wars during the paolian period caused the destruction of several of these buildings, including the towers of Tizzano, Caldane, Solenzara. The battle for the landing of the British troops of the Anglo-Corsican Kingdom in 1794, ruined the towers of Santa Maria della Chiappella and Mortella. By the end of the 18th century, few towers were still intact.

Heritage

Today the Genoese towers represent a considerable heritage. Of the 85 towers existing at the beginning of the 18th century, 67 still stand today. Some are in ruins; others are in very good state. Many of them are classified as Monuments historiques.

An important work of restoration, financed essentially by the local authorities although they are not owners, was produced to save some of them. Unfortunately, by lack of means and program of restoration, many of these symbols of the island continue to deteriorate.

Function

The garrison of a tower consisted of between two and six men (Corsican: torregiani), recruited among the inhabitants and paid from the local taxes. These guards were to reside permanently in the tower. They could move away no more than two days, for the supply and the pay, and one by one. They ensured the lookout with regular fires and signals: every morning and evening they assembled on the platform, informed navigators, shepherds and ploughmen about safety, communicating by fires with the closest towers located in their sight, and supervised the arrival of possible pirates.

In the event of alarm, a signal was given on the terrace at the top of the tower, in the form of smoke, fire or the sound of culombu (a large conch), warning the surroundings of the approach of hostile ships. It was followed by the general withdrawal of the people and animals in the interior of the country. The two closest towers in sight were ignited and so on, which made it possible to put the entire island in alarm in a few hours.

Certain garrisons had to be defended against the invaders, and combatants’ remains were found at their bases. Thus, the famous Torra di l'Osse took its name from the bones buried along its walls.

The towers were always insufficiently armed. They were used mainly as customs stations and daymarks. The torregiani often neglected their military role, to concentrate on the control of the maritime trade and the perception of various taxes. They were also trading wood and cultivating in the surrounding lands.

Although unjustified absence of a guard was prohibited under penalty of galley as well as the replacement by a person other than the titular guards, as times went by, some towers were deserted. They deteriorated, fell in ruins, or were destroyed for lack of defence.

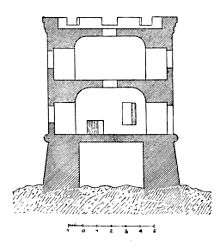

Architecture

The Genoese towers were constructed of stone blocks held together with mortar. Most of the towers were circular in plan although a few were square such as the Torra di Portu and the Torra di Pinareddu.[6] The circular towers were typically 12 metres (39 ft) in height and 10 metres (33 ft) diameter at the base reducing to 7 metres (23 ft) at the moulded string course marking the level of the first floor.[7][8] The base contained a cistern which was fed with rain water by an internal pipe from the terrace. The vaulted room on the first floor was connected to the terrace by a staircase built into the thick exterior wall and protected at the top by a small guerite. The terrace was surrounded by a low machicolated battlement. A doorway in the side of the tower at the first floor level was reached by a removable wooden ladder. A few towers were taller at around 17 metres (56 ft) in height and included a second internal vaulted room above the first.[6] Examples are the Torra di a Parata near Ajaccio and the Torra di Santa Maria Chjapella in Capicorsu.[9] The towers were manned by an officer and two or three soldiers who lived in the room on the first floor which had niches in the walls and a fireplace.[6][10]

See also

- History of Corsica

- List of Genoese towers in Corsica

- Martello tower, similar structure in Great Britain and Ireland

Notes and references

- Graziani 1992, pp. 17-18.

- Graziani 2000, p. 80.

- Graziani 2000, p. 73.

- Graziani 1992, pp. 134-137.

- Graziani 1992, p. 135.

- Colombani, Philippe; Harnéquaux, Mathieu; Istria, Daniel (2008). "Les tours génoises". L'Alta Rocca (PDF) (in French). Centre Régional de Documentation Pédagogique de Corse. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-2-86-620-212-5.

- Fréminville 1894, p. 48.

- Istria, Daniel; Harnéquaux, Mathieu. "La protection du littoral : un enjeu majeur aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles". Sevi - Sorru Cruzzini - Cinarca (PDF) (in French). Centre Régional de Documentation Pédagogique de Corse. pp. 17–20.

- Fréminville 1894, p. 51.

- Document d’objectifs NATURA 2000, Iles Pinarellu et Roscana, Zone spéciale de conservation FR9400585 (PDF). Conservatoire de l’Espace Littoral et des Rivages Lacustres. 2010. p. 31.

Sources

- Fréminville, Joseph de (1894). "Tours génoises du littoral de la Corse". Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques (in French): 47–57.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) The article was also published separately: Fréminville, Joseph de (1894). Tours génoises du littoral de la Corse (PDF) (in French). Paris. OCLC 494605587.

- Graziani, Antoine-Marie (1992). Les Tours Littorales (in French and Italian). Ajaccio, France: Alain Piazzola. ISBN 2-907161-06-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Source documents in Italian from the archives in the town of Genoa.

- Graziani, Antoine-Marie (2000). "Les ouvrages de défense en Corse contre les Turcs (1530-1650)". In Vergé-Franceschi, Michel; Graziani, Antoine-Marie (eds.). La guerre de course en Méditerranée (1515-1830) (in French). Paris: Presses de l'Université Paris IV-Sorbonne. pp. 73–144. ISBN 2-84050-167-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Braudel, Fernand (1995) [1973]. The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Volume 2. Renolds, Sîan trans. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20330-3.

- Graziani, Antoine-Marie (2001). "La menace barbareque en Corse et la construction d'un système de défense (1510-1610)". Revue d'histoire maritime (2–3): 141–160.

- Mérimée, Prosper (1840). Notes d'un voyage en Corse (in French). Paris: Fournier jeune. pp. 163–165.

- Phillips, Carla Rahn (2000). "Navies and the Mediterranean in the early modern period". In Hattendorf, John B (ed.). Naval Strategy and Power in the Mediterranean: Past, Present and Future. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Frank Cass. pp. 3–29. ISBN 0-7146-8054-0.

- Sutcliffe, Sheila (1973). Martello Towers. Cranbury, NJ: Associated Universities Press. ISBN 0-8386-1313-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genoese towers in Corsica. |

- Nivaggioni, Mathieu; Verges, Jean-Marie. "Les Tours Génoises Corses" (in French). Information on how to reach 90 towers. Includes 1,261 photographs.