Pindari

The Pindaris were irregular military plunderers and foragers in 17th- through early 19th-century Indian subcontinent who accompanied initially the Muslim army, later the Maratha army, and finally on their own before being eliminated in 1817-18 Pindari War.[1] They were unpaid and their compensation was entirely the loot they plundered during the war.[1] They were horsemen, foot brigades and partially armed, creating chaos and delivering intelligence about the enemy positions to benefit the army they accompanied.[2] The earliest mention of them is found during Aurangzeb's campaign in the Deccan, but their role expanded with the Maratha armed campaign against the Mughal empire.[2] They were highly effective against the enemies given their rapid and chaotic thrust into enemy territories, but also caused serious abuses against allies such as the Pindari raid on Sringeri Sharada Peetham in 1791. After several cases of abuse where the Pindaris plundered the territories of Maratha allies, the Maratha rulers such as Shivaji issued extensive regulations upon the Pindari contingent seeking to carefully limit their predatory actions.[2]

The majority of Pindari leaders were Muslims, but they recruited from all classes according to Encyclopaedia Britannica.[3] To fight them, competing groups of Pindaris formed from Hindu ascetics-turned-warriors.[4] According to David Lorenzen, after the collapse of the Mughal empire upon Aurangzeb's death, Nawabs and Hindu kingdoms entered into open conflicts and warring factions. Local landowners organized their own private armies, while the monks and ascetics of temples and monasteries transitioned into mercenary soldiers to protect their interests.[5] The Pindaris were dispersed throughout central India, the Deccan and regions that are now parts of Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Odisha.

By 1795, instead of being associated with a war effort, the armed Pindari militia groups sought easy wealth for their leaders and themselves.[6] There were an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 Pindari militia around 1800-1815 CE who looted villages, captured people as slaves for sale,[7] and challenged the authority of local Muslim sultanates, Hindu kingdoms, and the British colonies.[4] The period of 1795 to 1804 came to be called the "Gardi-ka-wakt" ("period of unrest") in north-central India.[8][9]

Lord Hastings of the colonial British era led a coalition of regional armies in early 19th-century to end the Pindari militia through military action and offering employment with regular salaries to the Pindaris in exchange for abandoning their freebooting, plundering habits.[1][10][11]

Etymology

The term Pindar may derive from pinda,[12] an intoxicating drink.[13] It is a Marathi name that possibly connotes a "bundle of grass" or "who takes".[1] They are also referred to as Bidaris in some historic texts.[14]

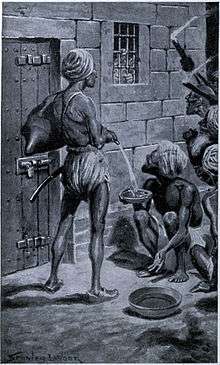

Appearance

The Pindaris of the Indian subcontinent adorned a Turban, these individuals were generally "half-naked" wearing only a girdle; they were armed with archaic models of the deadly Talwar, they also wore archaic footwear.

They were militantly associated with any established political communal principality or state.

Pindaris were often involved in proxy wars and carried out atrocities while they would extort wealth from their targeted areas.

History

Muslim sultanates and Mughal Empire era

According to Tapan Raychaudhuri, Irfan Habib et al., the Mughal army "always had in its train the "Bidari" pronounced in Arabic), the privileged and recognized thieves who first plundered the enemy territory and everything they could find". The Deccan sultanates and Aurangzeb's campaign in central India deployed them against Hindu kingdoms such as Golconda, and in Bengal. The unpaid cavalry got compensated for their services by "burning and looting everywhere".[14] The Hindu Marathas, in their war against the Mughals, evolved this concept to "its logical extreme", state Raychaudhuri and Habib, by expanding the Pindaris brigade, encouraging them not only to loot the Muslim territories but gather and deliver food to their regular army. The Maratha army never carried provisions, and gathered their resources and provisions from the enemy territory as they invaded and conquered more regions of the collapsing Mughal state.[14]

The Italian traveler Niccolao Manucci, in his memoir about the Mughal Empire, wrote about Bederia (Pidari), stating that "these are the first to invade the enemy's territory, where they plunder everything they find."[15]

According to the Indologist and South Asia historian Richard Eaton, plunder of frontier regions was a part of the strategy that contributed wealth and propelled the Sultanate systems in the Indian subcontinent.[16] The Ghaznavid sultans, states Eaton, "plundered north Indian cities from bases in Afghanistan in 10th- and 11th-century".[16] This strategy continued in the campaigns of the Delhi Sultanate, such as those of Khalji sultans who plundered the populations beyond the Vindhyas in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.[16] This pattern, states Eaton, created a "self-perpetuating cycle: cash minted from raided temple wealth could be used to recruit yet more slaves from beyond India, who could, in turn, be used for mounting further military expeditions undertaken for still more plunder".[17]

Babur similarly benefited from plundering raids into Hind, followed by withdrawal to Kabul, gaining financial resources. The plunder and wars ultimately overthrew the Delhi Sultanate and founded the Mughal Empire. Plunder, along with taxes and tribute payments contributed to growing imperial revenues for the Mughal rulers, states John Richards.[18] Beyond the direct raids by the Mughals, plunder of villagers and urban areas along with temples were a significant source of wealth accumulation by the local governors and Deccan sultanates.[19] Every victory of the Mughals between 1561 and 1687, states Richards, generated a "large amounts of plundered treasure from the hoards of defeated rulers".[20]

The Bidaris of the Aurangzeb's army and the Pindaris of the Maratha army extended this tradition of violence and plunder in their pursuit of the political and ideological wars. Shivaji, and later his successors in the name of his dynasty, included the Pindaris in their war strategy. Deploying the Pindaris, they plundered the Mughal and Sultanate territories surrounding the Maratha empire and used the plundered wealth to sustain the Maratha army.[21][22][23] They also plundered the ships loaded with goods and treasure leaving Mughal ports for the Arabian sea and those departing with passengers heading for Hajj to Mecca.[24][25]

The devastation and disruption by the Pindaris not only strengthened the Marathas, the Pindaris helped weaken and frustrate the Muslim sultans in preserving a stable kingdom they could rule or rely on for revenues.[21][22][23] The Maratha strategy also embarrassed Aurangzeb and his court.[25] The same Pindari-assisted strategy help the Marathas block and reverse the Mughal era gains in south India as far as Gingee and Trichurapalli.[26]

Maratha era

Marathas adopted the Bidaris militia of the earlier era. Their Pindaris were not from any particular religion or caste.[22] Most of the Pindari leaders who plundered for the Mughals and the Marathas were Muslims. The famed Pindari leaders in the historic literature include Namdar Khan, Dost Mohammad, Wasil Mohammad, Chitu Khan, Khajeh Bush, Fazil Khan, Amir Khan and others.[27] Similarly, Hindu leaders of Pindaris included the Gowaris, Alande, Ghyatalak, Kshirsagar, Ranshing and Thorat.[28] Hindu ascetics and monks were another pool that volunteered as militia to save their temples and villages from the Muslim invaders but also disrupted enemy supply lines and provided reconnaissance to the Marathas.[29]

According to Randolf Cooper, the Pindaris who served the Marathas were a volunteer militia that included men and their wives, along with enthusiastic followers that sometimes swelled to some 50,000 people at the frontline of a war. They moved swiftly and performed the following duties: destabilize enemy's standing army and state apparatus by creating chaos; isolate enemy armed units by harassing them, provoke and waste enemy resources; break or confuse the logistical and communication lines of the enemy; gather intelligence about the size and armament of the enemy; raid enemy food and fodder to supply resources for the Marathas and deplete the same for the enemy.[2]

The Pindaris of the Marathas did not attack the enemy infantry, rather operated by picketing the civilians, outposts, trade routes and the territorial sidelines. Once the confusion had set in among the enemy ranks, the trained and armed contingents of the Marathas attacked the enemy army. The Marathas, in some cases, collected palpatti – a form of tax – from the hordes of their Pindari plunderers to participate with them during their invasions.[2]

The Pindaris were a major resource for the Marathas, but they also created abuse where the Pindaris raided and plundered the allies. Shivaji introduced extensive regulations to check and manage the targeted predatory actions of the Pindaries.[2]

During the Third Battle of Panipat, Vishwasrao was in command of thousands of Pindari units.

Pindari War (1817-18)

After the arrival of the British East India Company among the chaos of a collapsed Mughal Empire and warring kingdoms, the Pindaris emerged as centers of violence and power. By late 18th-century, the Maratha empire had fragmented, the British colonial era had arrived and the Pindaris had transformed from being involved in regional wars to looting for the sake of their own and their leaders' wealth.[7] They conducted raids for plunder to enrich themselves, or to whichever state was willing to hire them. Sometimes they worked for both sides in a conflict, causing heavy damages to the civilian populations of both sides. They advanced through central India, Gujarat and Malwa, with protection from rulers from Gwalior and Indore.[1][30][31] With the plundered wealth, they had also acquired cannons and more deadly military equipment to challenge local troops and law enforcement personnel. The Amir Khan-linked Pindaris, for example, brought 200 canons to seize and loot Jaipur.[32] According to Edward Thompson, the Pindaris led by Amir Khan and those led by Muhammad Khan had become nearly independent mobile satellite confederacy that launched annual loot and plunder campaigns, after the monsoon harvest season, on rural and urban settlements. Along with cash, produce and family wealth, these Pindari leaders took people as slaves for sale. They attacked regions under British control, the Hindu rajas, and the Muslim sultans.[7]

Ultimately, the British and the general population became so frustrated that they formed a coalition to end the Pindari habits. In early 19th-century, this precipitated the Pindari War. Lord Hastings, with the approval of the Court of Directors of the East India Company, decided to eliminate the Pindaris. In cooperation with armies from Gujarat, the Deccan and Bengal, some 120,000 troops surrounded the Malwa region and Gwalior to force the surrender and outlawing of Pindaris.[1][30][31]

In addition to the military action, the British coalition also offered regular employment to some of the Pindari militia by converting them into a separate contingent of its forces. A minority were given jobs as police and offered pensions or Nawab position along with land to their leaders such as Namdar Khan and Amir Khan.[11] A few such as Saiyid Ahmad of Rai Bareilly, states Thomas Hardy, shifted to the Islamic Jihadi movement, while small bands took to sporadic crimes of harassing tradespeople and farmers through kidnapping and blackmail after the end of the Pindari war.[11]

References

- Pindari: Indian History, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Randolf Cooper (2003). The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India: The Struggle for Control of the South Asian Military Economy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–34, 94–95, 303–305. ISBN 978-0-521-82444-6.

- "Pindari". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Martine van Woerkens (2002). The Strangled Traveler: Colonial Imaginings and the Thugs of India. University of Chicago Press. pp. 24–35, 43. ISBN 978-0-226-85085-6.

- David N. Lorenzen (2006). Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History. Yoda Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-81-902272-6-1.

- Banerjee, Tarasankar (1972). "The Marathas and the Pindaris: A Study in Their Relationship". The Quarterly Review of Historical Studies. 11: 71–82.

- Edward Thompson (2017). The Making of the Indian Princes. Taylor & Francis. pp. 208–217, 219–221. ISBN 978-1-351-96604-7.

- Banerjee 1972, p. 77

- Katare, Shyam Sunder (1972). Patterns of Dacoity in India: A Case Study of Madhya Pradesh. New Delhi: S. Chand. p. 26.

- Vartavarian, Mesrob (2016). "Pacification and Patronage in the Maratha Deccan, 1803–1818". Modern Asian Studies. 50 (6): 1749–1791.

- Hardy, Thomas (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–39, 51–52. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- Russell, R. V. (1 January 1993). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120608337.

- (India), Central Provinces (1 January 1908). Nimar. Printed at the Pioneer Press.

- Tapan Raychaudhuri; Irfan Habib; Dharma Kumar, Meghnad Desai (1982). The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 1, C.1200-c.1750. Cambridge University Press. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

- Niccolò Manucci; William Irvine (Translator) (1965). Storia do Mogor: or, Mogul India, 1653-1708. by Niccolao Manucci. Editions. p. 431.

- Richard M. Eaton 2005, pp. 24-25.

- Richard M. Eaton 2005, pp. 24-25, 33, 38-39, 56, 98.

- John Richards 1995, pp. 8-9, 58, 69.

- John Richards 1995, pp. 155-156.

- John Richards 1995, pp. 185-186.

- John Richards 1995, pp. 207-208, 212, 215-220.

- Kaushik Roy (2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740-1849. Taylor & Francis. pp. 102–103, 125–126. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.;

Robert Vane Russell (1916). The principal castes and tribes of the Central Provinces. Macmillan and Company, limited. pp. 388–397. - Randolf Cooper 2003, pp. 32-34.

- Abraham Eraly (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books. pp. 471–472. ISBN 978-0-14-100143-2.

- Jack Fairey; Brian P. Farrell (2018). Empire in Asia: A New Global History: From Chinggisid to Qing. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1-4725-9123-4.

- Jos J. L. Gommans (2002). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500-1700. Psychology Press. pp. 191–192, context: 187–198. ISBN 978-0-415-23989-9.

- R.S. Chaurasia (2004). History of the Marathas. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-81-269-0394-8.

- LKA Iyer (1965). Mysore. Mittal Publications. pp. 393–395. GGKEY:HRFC6GWCY6D.

- Rene Barendse (2009). Arabian Seas 1700 - 1763 (4 vols.). BRILL Academic. pp. 1518–1520. ISBN 978-90-474-3002-5.

- Tanuja Kothiyal (2016). Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–113, 116–120 with footnotes. ISBN 978-1-107-08031-7.

- Adolphus William Ward; George Walter Prothero; Stanley Mordaunt Leathes (1969). The Cambridge Modern History: The growth of nationalities. Cambridge University Press. pp. 725–727.

- Edward Thompson (2017). The Making of the Indian Princes. Taylor & Francis. pp. 179–180, 218–223. ISBN 978-1-351-96604-7.

Bibliography

- Randolf Cooper (2003). The Anglo-Maratha Campaigns and the Contest for India: The Struggle for Control of the South Asian Military Economy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82444-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richard M. Eaton (2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-25484-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- John Richards (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-58406-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Pindari Society and the Establishment of British Paramountcy in India

- Pindari in The tribes and castes of the central provinces of India, Volume 1, by R.V. Russell, R.B.H. Lai