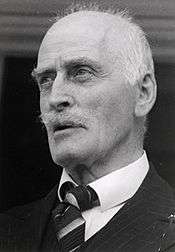

Gabriel Langfeldt

Gabriel Langfeldt (23 December 1895 – 28 October 1983)[1] was a Norwegian psychiatrist. He was a professor at the University of Oslo from 1940 to 1965. His publications centered on schizophrenia and forensic medicine. He was involved as an expert during the trial against Hamsun, and wrote a book about Quisling.[1][2]

Gabriel Langfeldt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 December 1895 Kristiansand, Norway |

| Died | 28 October 1983 (aged 87) Oslo, Norway |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Occupation | Psychiatrist |

Career in psychiatry

Born in Kristiansand to Carl Gerhard Magnus Langfeldt, a bank director, and his wife Gudrun Amalie Leversen,[1] Langfeldt obtained examen artium at Kristiansand Cathedral School and became Candidate of Medicine at the University of Oslo in 1920. He earned his degree in medicine in 1926 with a thesis on the endocrine glands and autonomic nervous system in relation to schizophrenia.[1]

After working as a district physician and hospital physician, Langfeldt became assistant physician at Neevengården Hospital in Bergen in 1923, and worked there until 1929 when he became a psychiatrist with the police.[1] As a police psychiatrist, he started the first observation department for psychiatric patients in an effort to avoid having to put them in prison while they were waiting for an ordinary hospital place.[3]

In 1935, he started working at the psychiatric clinic of the University of Oslo. He became leader of the clinic in 1940, appointed by the German-led occupation administration and confirmed by the legitimate Norwegian government in 1945.[1]

He published further studies on schizophrenia in 1937 and 1939, in which he developed a distinction between "typical schizophrenia" and "schizophreniform psychoses". While the former had a poor prognosis, he believed that the latter could include affective disorders and delusions but lacked several of the typical schizophrenic symptoms. and therefore had a much better prognosis. This theory attracted international attention.[1][4] Langfeldt was a keynote speaker at the 2nd International Congress for Psychiatry held in Zürich in 1958 devoted to knowledge on "groups of schizophrenia".[3] He travelled to Vienna to study the insulin shock therapy against schizophrenia developed by Manfred Sakel, but was skeptical of the method.[3]

He chaired the Norwegian Board of Forensic Medicine from 1946 to 1965.[1]

Seeing students lacking a textbook in psychiatry, he published one in 1951, which had a large influence in Norway and Nordic countries.[3]

Langfeldt also published several books on psychological themes for the general public, among them Nervøse lidelser og deres behandling (Nervous Diseases and Their Treatment), Hvorfor blir et ekteskap ulykkelig? (Why Does a Marriage Become Unhappy?) and Sjalusisyken (The Jealousy Disease).[1]

Psychiatric evaluation of Knut Hamsun

In October 1946, Langfeldt was assigned the task of making a judicial observation of Norwegian author Knut Hamsun, who had actively supported the Nazi regime during the German occupation of Norway. Ørnulv Ødegård was the other doctor who participated in the observation, which took place at the University's clinic at Vindern for four months until February 1946.[5]

The doctors found that Hamsun had developed atherosclerosis already before 1940 and that he was further weakened by his first cerebral hemorrhage in 1942, which caused aphasia.[6] The diagnosis was that Hamsun had "permanently impaired mental capabilities" (varig svekkede sjœlsevner),[7][8] a diagnosis particular for judicial observations in Norway. Based on the diagnosis, the prosecutors decided not to pursue criminal proceedings against Hamsun.[6]

In 1949, Hamsun published Paa gjengrodde Stier (On Overgrown Paths), a mixture of self-biography and storytelling,[9] covering the period from when he was arrested in 1945 to the Supreme Court verdict in 1948. He portrayed Langfeldt as an abusive man who enjoyed power: "he could bully me as much as he wanted – and he wanted a lot", he wrote.[5] "In his personality, in his way of being, Mr. Langfeldt sets himself way above everybody, with his incontestable learning, with his silence at any disagreement, with his show of superiority which seems merely contrived [...] I feel the psychiatrist would have benefited from learning how to smile a little. A smile directed at himself now and then".[10] A main theme for Hamsun is that he had deserved an ordinary trial instead of a stay at a psychiatric clinic and a psychiatric diagnosis. He insists in the book that the hospitalization had harmed his health more than anything else.[9]

At first Hamsun had difficulty getting his book published. Langfeldt demanded that his name should not be included and the publicist initially demanded the same, but later published the book with Langfeldt's name in it.[6]

As On Owergrown Paths was considered to have good literary standard, the book raised questions on whether Langfeldt and Ødegård had been correct in their diagnosis, though most psychiatrists agreed with them.[6] One critic was the author Sigurd Hoel. In 1952, Langfeldt argued that the diagnosis of Hamsun was correct and stressed that the diagnostic finding benefited both Hamsun's legacy and Norway as a nation. Compared to the original medical evaluation, Langfeldt in 1952 put more emphasis on organic brain disease than on pathological character traits.[5]

Some critics of the diagnosis argued that it might have been influenced by the Norwegian government,[6] which didn't want to see Hamsun in prison due to his advanced age and high status as a writer. Psychiatrist Einar Kringlen, who knew Langfeldt and Ødegård, rules out this possibility.[6] The Danish author Thorkild Hansen sharply criticized the psychiatric examination of Hamsun in his 1978 book Prosessen mot Hamsun (The Process Against Hamsun), leading Langfeldt and Ødegård the same year to publish the book Den rettspykiatriske erklæring om Knut Hamsun (The Forensic Psychiatric Statement on Knut Hamsun) regarding the medical evaluation they had performed.

A post-mortem psychiatric evaluation by Sigmund Karterud and Ingar Sletten Kolloen concluded that Hamsun had an unspecified personality disorder but was legally sane.[6]

In his 1969 book on Vidkun Quisling, Gåten Vidkun Quisling (The Riddle of Vidkun Quisling), Langfeldt argued that Quisling should have also undergone a psychiatric examination and that he might have suffered from paranoia.[11]

Humanism

Originally having religious inclinations, Langfeldt gradually developed a secular humanist lifestance. When the Norwegian Humanist Association was founded in 1958, he became a central figure in the organization and chaired the International Humanist and Ethical Unions congress in Norway in 1962.[1] He wrote a book about Albert Schweitzer in 1958 and later corresponded with him.[3] In 1966 he wrote the book Den gylne regel og andre humanistiske moralnormer (The Golden Rule and Other Humanistic Morale Norms).[1]

Personal life

Langfeldt married three times. His marriage to his first wife, Eva Antoinette Tutein Poulsson, daughter of professor Edvard Poulsson, was dissolved in 1928; that same year, he married Hjørdis Nilssen, a secretary. His third wife, Else Marie Nilssen, was a sister of his second, deceased wife.[1]

Langfeldt continued to work as a psychiatrist until he was in his eighties. He died in Oslo in 1983. He was a brother of Einar Langfeldt.[1]

Awards and recognition

- Member, Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters (1941)

- Stanley R. Dean Award for research in schizophrenia

- Honorary member, Norwegian Psychiatric Association (1965)

- Honorary doctorate at University of Helsinki (1966)

References

- Retterstøl, Nils. "Gabriel Langfeldt". In Helle, Knut (ed.). Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- "Gabriel Langfeldt". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- Per Anchersen and Leo Eitinger (1958) Nervøse lidelser og sinnets helse : festskrift til Gabriel Langfeldt på 60-års dagen (in Norwegian) Aschehoug. Oslo. Pp 9–12 Online access via National Library of Norway for Norway-based IPs

- AL Bergem et al (1990) Langfeldt's schizophreniform psychoses fifty years later British Journal of Psychiatry September 1990 157:351–4. Retrieved from NCBI 22 January 2015

- Gunvald Hermundstad (1999) Psykiatriens historie Ad Notam Gyldendal. Online access via the National Library of Norway for Norwegian IPs

- Einar Kringlen Knut Hamsuns personlighet (in Norwegian) Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift 1/2005. Retrieved via Idunn.no 29 January 2015

- Monica Zagar (2009) Knut Hamsun: The Dark Side of Literary Brilliance (New Directions in Scandinavian Studies) University of Washington Press

- Peter Aaslestad The Patient as Text: The Role of the Narrator in Psychiatric Notes, 1890–1990, p. 44

- Fredrik Wandrup (9 July 2008) Den gåtefulle dikteren (in Norwegian) Dagbladet

- Knut Hamsun (1949/1958) On Owergrown Paths. Quote taken from Peter Aaslestad The Patient as Text: The Role of the Narrator in Psychiatric Notes, 1890–1990, p. 44

- Gåten Vidkun Quisling by Gabriel Langfeldt. Review by: John M. Hoberman (subscription required) Scandinavian Studies, Vol 46, No 3, pp. 289–290. Via Jstor