GPS drawing

GPS Drawing, also known as GPS Art and Strava Art, is a method of drawing where an artist uses a Global Positioning System (GPS) device and follows a pre-planned route to create a large-scale picture or text on a map. Alternatively, in the freestyle method of GPS Drawing, the path followed by the GPS receiver is random.[1] Artists usually run or cycle the route—while cars, vans, boats and aeroplanes are utilized to create larger pieces.

Laura Kurgan first introduced the concept of recording GPS locations over time, as displayed on a computer screen. In the accompanying text to her 1994 art exhibit "You Are Here: Information Drift",[2] she states: “A GPS receiver located, for the duration, on Storefront’s roof transmits uncorrected real-time position readings to a computer in the gallery.” Kurgan brought her show "You Are Here: Museu" to Barcelona in 1995.[3] It was just a matter of time before other artists would adapt this concept to create GPS-themed art, by using various modes of travel to follow the pre-planned or unintentional path of a GPS receiver.[4]

Planning

GPS artists can spend many hours finding a certain image or text hidden in a map or can sometimes simply see an existing image in a map due to Pareidolia. In many cities and towns the road layout and landscape restricts the routes available so artists have to find creative ways to show their pictures or characters. In cities where there is a strong grid pattern an 8-bit style or pixelated images can be created of almost any object or shape. Many artists will create paper or digital maps of their route to follow on their journey.

Artistic style

There are many approaches to GPS Drawing which an artist can choose depending or their means of travel and the landscape around them.

Roads, trails, and paths only

This style uses only pre existing roads, paths, trails, etc. which can make it more challenging to find a route and plan the artwork. On the other hand following these paths makes navigation during the journey much easier and the artwork is more likely to reflect the original plan. This is how the majority of GPS artworks are made.

Freehand on open ground or in open air or open water

Freehand GPS drawing is where artist creates a shape on open ground without following existing paths which means the artist has to watch their progress in real time on their GPS device. Artists can run or cycle over open ground such as parks, fields, and car parks. Artists in cars and other motor vehicles can draw shapes on large open areas such as deserts, airfields, and beaches. Almost all artworks created by aircraft and watercraft use this technique as they are not restricted by human and physical geography. Freehand GPS drawing opens unlimited possibilities but without waypoints and existing routes it is very easy to lose track of your progress and make mistakes.

Connect the dots

By pausing the GPS device and restarting it at different locations an artist is able to draw straight lines across the map in a similar way to a connect the dots puzzle. This means the artist can draw over the built environment and over physical barriers such as rivers and hills. Though this can create very striking images and open up new possibilities, most artists do not use technique.

Adding extra images

Some artists add extra images or lines to the map after they have created the route. They can do this to simply add googly eyes to an animal or face or go further and add lines and other features which help viewers see what they have drawn. Other times an artist will show a photo or other image alongside their drawing if it is not clear at first glance what has been drawn.

Display

Most people use a route mapping app or other service to display their drawing online and to share on social media. Popular apps include Strava, Map My Run, and Garmin. Many artists also import their route into Google Maps, OpenStreetMap, Viewranger, and other map services before capturing the image to display and share. This gives the artist the option of expanding and cropping the image, orienting it another way, or tilting the map to add perspective. Some artists use false color maps then choose contrasting colors for their route to create vivid images.

Artist Jeremy Wood often displays his drawings without a showing any map underneath. He is able to do this as the drawings are so detailed you can see the shape of the built environment or landscape in the lines. "Traverse Me" not only a maps out The University of Warwick campus but also includes the map title, other text and images, a compass, scale, date signature, etc. It was made by walking 238 miles over 17 days.

Examples and artists

In 1999, Reid Stowe was probably the first artist to employ waypoints on a GPS-verified journey in order to render a large-scale art object.[5] This work of GPS Art, representing a baby sea turtle (1900 miles long and 1400 miles wide, with a perimeter of 5,500 miles), was performed with a two-masted schooner during the Voyage of the Sea Turtle.[6][7][8] He made two more large GPS-verified drawings on his 1000-day voyage.[9]

The idea was first implemented on land by artists Hugh Pryor and Jeremy Wood, whose work includes a 13-mile wide fish in Oxfordshire, spiders with legs 21 miles long in Port Meadow, Oxford,[10] and "the world's biggest "IF'" with a total length is 537 km, and the height of the drawing in typographic units is 319,334,400 points.[10] Typical computer fonts at standard resolutions are between 8 and 12 points.

The largest GPS drawing was "PEACE on Earth (60,794.07km)" unofficially in 2015 and "MARRY ME (7,163.67km)" officially in 2010.[11] They were both created by Yassan.

In 2016, musicians Shaun Buswell & Erik Nyberg travelled around the United Kingdom drawing a 400+ mile penis across England and Scotland.[12]

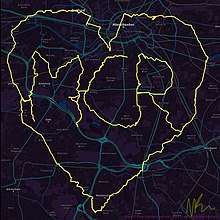

In 2018 artist Nathan Rae created a #WeLoveManchester piece as part of the cememorations of the Manchester Arena Bombing.[13]

One of the most prolific GPS artists is the artist known as WallyGPX who, as of October 2018, has created over 500 pieces of GPS art. He uses pencil and paper to plan the routes around his home city of Baltimore which he then creates by bicycle.

References

- With GPS, World Is Your Canvas Archived 2016-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. Wired, June 22, 2002. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- You Are Here: Information Drift Archived 2019-10-30 at the Wayback Machine. Storefront for Art and Architecture. March 12 to April 16, 1994.

- Exhibition - Laura Kurgan - You Are Here Archived 2019-10-31 at the Wayback Machine. MACBA. November 30, 1995 - February 25, 1996.

- The Existentialism of GPS Archived 2019-10-30 at the Wayback Machine. The Atlantic, June 17, 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- COMPREHENDING REID STOWE: His Various Purposes Archived 2019-10-30 at the Wayback Machine. Boats.com, June 3, 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- The Voyage of the Sea Turtle . (Reid Stowe). Cruising World, August 2000, p. 44. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Reid Stowe Art Archived 2016-01-28 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Newlyweds to Test Marriage’s Sea Legs on 1,000-Day Voyage Archived 2019-10-30 at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times, June 6, 1999. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- The Man Who Fell to Shore Archived 2019-10-28 at the Wayback Machine New York Magazine, 17 September 2010. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Kimmelman, Michael (14 December 2003). "2003: The 3rd Annual Year in Ideas; GPS Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- Meet the Japanese artist who made the world’s largest GPS drawing for his marriage proposal. Venture Beat, 17 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Two musicians have drawn a giant "wedding tackle" during their UK tour using GPS tracking". The Ocelot. 22 February 2017. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Johnson, Helen (2018-05-23). "The runner who made a 67-mile Strava heart all around Manchester". men. Archived from the original on 2018-11-09. Retrieved 2018-11-02.